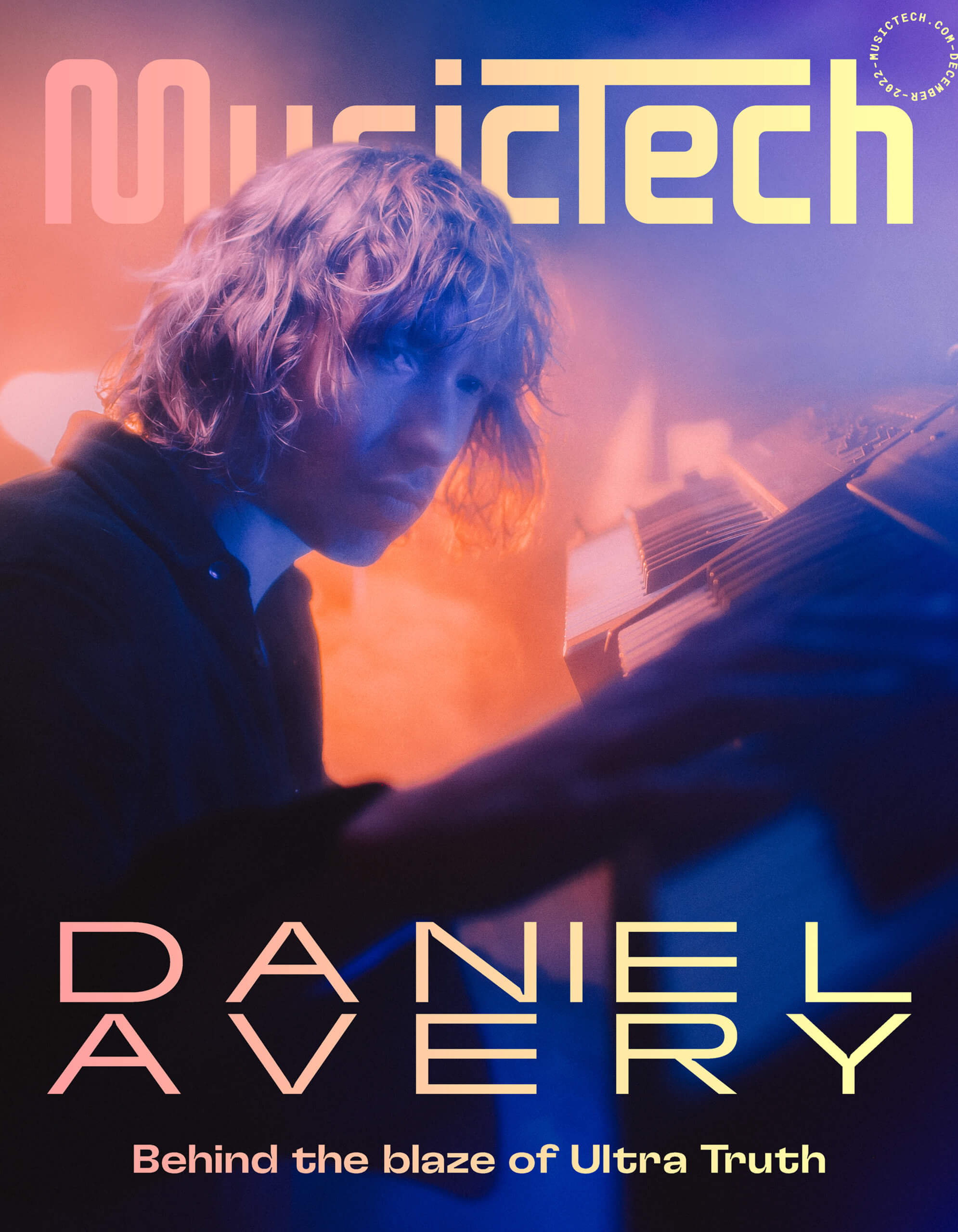

Daniel Avery: “Instead of hiding things that feel like mistakes, I push those to the front”

How the British producer channels atmosphere, synthesis, Andrew Weatherall’s teachings, and the dancefloor into his sixth album, Ultra Truth.

Image: Sam Neill for MusicTech

Daniel Avery is sitting inside a metal box. His Thameside studio is housed in a converted shipping container, where he’s been working for the past decade. From the window, he can see the O2 Arena and the towers of Canary Wharf, which line up like a built equivalent of a graphic equaliser. The nicer view, he says, is of the Thames itself and, further downriver, the cable cars at Woolwich, which look like “little dots going across the water”. “It’s very quiet and peaceful,” says the Bournemouth-born DJ and producer. “There’s a sense of being alone and serene. I try and come down as much as I can, even when I have no intention of making music. It’s a place I can properly listen to what I’m making.”

Avery’s listening process takes place in two stages. First is the kind of listening he does when he’s working away in his metal bolthole, soothed by the rise and fall of the Thames. The other comes when he’s on the move – and, given his packed schedule of international DJ bookings and live shows, which included a recent tour with Nine Inch Nails, he’s on the move rather frequently. “I’ve always struggled with making music while travelling,” he says, “but listening and absorbing it, that happens when walking or flying or on a train.” It is, he says, the “most crucial listening phase” of an album.

Ultra Truth, his sixth album, hit the top of the UK dance charts upon its release in November. Avery’s journey began with 2013’s Drone Logic and includes notable mix compilations for Fabriclive the same year and DJ Kicks in 2016, as well as 2020’s collaborative ambient album with NIN’s Alessandro Cortini, Illusion of Time. The new record was produced with long-time collaborators Ghost Culture and Manni Dee, and features an array of friends and family who provide vocals and snippets of recorded speech, all expertly woven into Avery’s dream-state techno, breakbeats, and drone-drenched deep house.

One of these is Kelly Lee Owens. The Welsh electronic producer and Avery first met when they both worked in Pure Groove Records, back when he moved to London from the south coast. “She was the voice of Drone Logic 10 years ago and it was nice to complete the circle, now that she’s a bona fide superstar in her own right,” he says. Then there’s HAAi, “a very dear friend”, who features on Wall of Sleep and Chaos Energy, and Jonnine Standish of HTRK, on Only. “Lots of circles got completed on this record, which is one of the most pleasing things.”

The result of these completed circles is a sonic world that is meditative and propulsive. Listening to Ultra Truth is to be deeply immersed in emotion and mood. It’s warm but there are undertones of sadness. “I wanted to set it on fire. I wanted it to sound like it was ablaze,” Avery says. “Every edge is distorted. Every drum is pushed to near breaking point. Not in an aggressive sense, but in the way that there’s beauty within that distortion. That goes back to my love of a lot of guitar music and especially shoegaze. There’s beauty within those flames.”

Another word he uses is “cavernous”, an effect achieved via judicious use of reverb. “Layers and layers of reverb and different tails of reverb feeding into each other and playing off each other to add to that depth, and to add to that feeling that this record stands tall,” he says. “Even when you’re listening on headphones, it sounds bigger than the space you’re sat in.”

It’s a sound that channels a lifetime of soaking up music from the dancefloor, specifically from techno clubs. “That idea of putting everything inside a huge cathedral or a cave comes from techno, being inside a club, and hearing a kick drum that sounds like it’s 100 feet tall. It’s two of my main passions coming together – the fire of a shoegaze record and the depth of a techno club.” The last time Avery spent serious time on the club dancefloor was at Berghain. “I went with my girlfriend – it was her first time in that building. We spent an inhuman amount of time in that place but loved every single second of it. That place is like no other.”

Avery recognises that something particular happens when you’re listening and moving at the same time. “There’s something very primal about that feeling. It’s very freeing.” He pauses. “What’s the Madonna line? ‘Only when I’m dancing do I feel this free’? It’s true. It can become a cliché but everyone inside a club is searching for some kind of higher energy, some kind of higher power and that search, when it happens in a communal setting, is something that almost cannot be described. It’s not like dancing on your own. It must go back thousands of years, sharing the search for something and moving to the same beat of the drum.”

It was the music of early 1990s post-club sessions that first piqued Avery’s interest in electronics – the sounds of Autechre, Aphex Twin and Warp’s Artificial Intelligence series. “To me, as a kid, it sounded like alien music, completely futuristic, but at the same time there was melody and beauty, so there was a human element to cling on to. There was always enough musicality and a song within everything so you could fall in love with the sound.”

He might have fallen in love with those sounds but he’s not blind to reality. The world that music was made for no longer exists. Producers in the 2020s – and their listeners – need music that reflects the world as it is today, with all its intense upsides and downs. The hardware of yesteryear, though, can still play an important role in making it. Avery is sitting in front of his Roland TR-808 (“one of my most prized possessions”), Roland SH-101 (“an integral part of everything I’ve ever done”), and Roland JX3P (“I love the warmth of the pads and really beautiful layers of sound”).

He’s clear about how he wants to use vintage kit. “The most exciting thing for me is those intersections where old and new cross over,” he says. “Taking old bits of equipment and feeding it through new processors and plugins and seeing what comes out the other side. I think there’s something really magical about that.”

The modern-day plugins he favours include Crystallizer by Soundtoys, which he uses to create beautiful, harmonic layers of pads. “It has a real angelic quality, a really satisfying sound,” he says. He’s also a fan of the FabFilter Saturn, which combines EQ and distortion. “I’m sat in front of a real [Roland] Space Echo but, as with anything that old, the maintenance has become pretty difficult,” he explains, adding that North London audio solutions company Funky Junky occasionally help him with decrepit kit.

“I love the idea of tape saturation but I was getting frustrated by the fact that it didn’t work half the time. There’s a plugin called the M Saturation by MeldaProduction, which I found gives a pretty satisfying replication of tape saturation, something I push pretty hard on everything.” His track with Manni Dee, Meanwhile the Night Gets Darker, appeared on Make Noise’s recent Strega Musica album – a compilation of music made on the Strega – alongside tracks by Caterina Barbieri, Julianna Barwick and Daniel Miller. The Strega is a patchable analogue desktop synth built by Avery collaborator Alessandro Cortini. “I don’t know how he’s managed it but he’s got his personality into a bit of electronic equipment,” Avery says. “It makes a really beautiful noise.”

Avery is less effusive about modular synthesis. “I fully respect the world of modular and I think people who can master it can make unbelievable sounds,” he says. “From my limited experience, I find my patience runs out too quickly. If I can’t get at least halfway to where I want relatively quickly then I become frustrated. For me, it’s about getting ideas out, and that takes priority over labouring over a sound for two days. I generally have a rule in the studio which is that if a track has not taken some kind of shape within a day then it’ll probably get discarded. Stuff gets worked on for much longer than that, but if a skeleton of a track hasn’t formed within that time, then it doesn’t often work for me.”

He is heavily into creating atmosphere, though. Some of this is supplied by the contact mic he uses to record the sound of passing boats on the water, or whatever is going on outside his studio, a technique he’s been using for the past few years. “That’s become a really big part of the sound, just creating atmosphere,” he says. “Turning it into an atmosphere or a hiss or a kind of fog that can sit over the record. It’s not something you can always pinpoint sonically, but you can feel it, and when you take it away a track can feel empty.”

Additionally, Avery makes a feature out of something that music tech school – “which I have not attended” – traditionally teaches students to hide: the hiss of old equipment. “Instead of hiding things that might feel like mistakes, I push those to the front, pushing the hiss, pushing the distortion, pushing the atmosphere that an old bit of equipment can throw up; that’s really important to me.”

Now, Avery is taking the album – and that atmosphere – out on the road, with live shows in Paris, London and Glasgow. The first taste of Ultra Truth, though, came in the shape of Lone Swordsman, which Avery made in honour of his friend Andrew Weatherall, who died in February 2020. Weatherall was revered during his lifetime and his cultural importance has only been amplified since his untimely passing. Avery’s track sounds like the presence of an absence, all loss and warmth and shades of Weatherall’s Smokebelch II, released in 1993 as Sabres of Paradise. It’s a sonic expression of grief and gratitude, all wrapped up together.

Weatherall was a big reader and shared recommendations with Avery. One of those was London Fog: The Biography, by Christine Corton. “It’s about the history of the fog over London, particularly in Victorian times, and how it informs a lot of art and culture that has come out of it. What I took from that – and this is a very Andrew teaching – is that you can’t help but be who you are,” he says. “The best thing about Andrew, for me, and the legacy he left behind, was the idea to always be yourself when producing and to realise that trends come and go, styles fade in and out, but if you can produce something that sounds like you, whatever genre it comes from, you’re doing alright.

“Anyone who met Andrew would understand that he would not have considered himself any kind of mentor or teacher or anything like that. He’d scoff at that idea. Instead, he just led by example, just by being himself at all times and allowing his voice to be heard in the music, whatever form that took. It could have been post-punk or a chugging psychedelic club record or something that contained some spoken-word. It was always him, and you could tell straight away. That’s what I think his legacy is, and that’s what I’ve taken from him.”

Avery is drawn back to his shipping container studio, and the view from inside. “It’s a very spiritual feeling to simply put a record on and sit and watch, and remind yourself that making music is important. But ultimately just to sit and be is far more important.”

Daniel Avery’s Ultra Truth is out now.