Getting A Vintage Sound – Keeping Things Simple

We’re back with part two of our extensive guide to vintage sound. This time we’re looking at the Abbey Road effect, stereo kit and the sound of Motown… The Abbey Road effect At the dawn of the multi-track era in the early 1960s, when four-track recording was introduced, most pop records were still cut live […]

We’re back with part two of our extensive guide to vintage sound. This time we’re looking at the Abbey Road effect, stereo kit and the sound of Motown…

The Abbey Road effect

At the dawn of the multi-track era in the early 1960s, when four-track recording was introduced, most pop records were still cut live with a complete, or almost complete, backing track and, often, a lead vocal. The days of each instrument, never mind each element of the drum kit, occupying its own track, was still a long way off. EMI’s world-famous Abbey Road Studios in London first employed four-track pop recording in 1963, just as The Beatles were coming on to the scene, and shortly before they became a global phenomenon.

Along with their producer George Martin and EMI’s brilliant engineering staff, the group’s role as serial pioneers in recording technology cannot be overstated. Their constant development and demands, as well as their influence on their contemporaries, pushed the boundaries of recording practice more than any other artist.

Abbey Road’s equipment up until 1968 was almost exclusively valve-driven. The EMI-designed-and-built REDD.51 mixing consoles used to record The Beatles and the hits of many other classic

1960s acts employed the superb-sounding REDD.47 microphone preamplifier, which is now available as single-channel 19-inch rackmount unit by Chandler Ltd.

At over £2,000, it’s not cheap – however, when Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick heard this fabulous valve unit, his response was: “It has that sound!” Waves offers a more wallet-friendly software version for those wanting a taste of the authentic 1960s EMI sound in a limited budget.

One of the most revered sounds created at Abbey Road was Ringo Starr’s drum sound, explained in the Starr Sound boxout in this feature. However, it’s worth noting that most other instruments and vocals were recorded quite simply – engineers rarely used two microphones when one would do. It was far more common for each engineer to have his own favourite mic than to combine, for example, three different mics to record a guitar amplifier.

That’s not to say engineers were afraid of experimentation on the contrary, rival studios’ original methods were closely guarded secrets – rather, the consoles of the day had insufficient inputs to accommodate such extravagant multi-mic’ing techniques.

A great technique for achieving a typical early-to-mid-1960s drumkit sound is to use a single overhead mic to capture an overall balance of the snare drum, toms and cymbals, with a second mic placed in front of, or inside the bass drum. These two mics can then be sent to a single compressor, set to a medium-fast attack time and fast release, which will, with some fine-tuning, produce a cohesive sound with plenty of energy and drive.

As always, the source sound has to be right in the first place, so make sure the kit is tuned properly before recording. Sometimes, what might be heard as imperfections in the sound can actually add character when going for an obviously retro vibe – check out The Searchers’ 1964 chart topper Needles And Pins; once you’ve spotted that squeaky bass-drum pedal, you can never un-hear it.

Get a room

Recreating classic analogue sounds digitally has never been easier. However, playing a digital stem through a speaker into a room and blending the two signals can add a lovely warm analogue roundness to a cold or clinical signal. If you have a reverberant bathroom or kitchen, try rigging up a temporary echo chamber with a loudspeaker at one end and a microphone at the opposite end, pointing towards the tiled wall.

Legendary recording pioneer Joe Meek famously used the bathroom in his home-built studio, sometimes in conjunction with electronic spring reverbs. For the longest available reverb time, remove any bath mats, towels and other absorbent materials. Filtering the signal before sending to the speaker (as explained in the Vintage ’Verb boxout) will help create a unique small echo-chamber sound. Explore your recording environment to find useful and interesting ambient spaces.

Experimentation is key to producing a trademark sound; even the inside of an oven can be used to create a short, metallic reverb. Try everything, no matter how odd the concept might be – it’s what we all did before digital outboard became available. See every space as potential ambient enhancement and discover what works for you.

Saturation point

One of the advantages of recording to analogue tape was the way you could overdrive it by recording a ‘hot’ signal, louder than would be acceptable, to produce a clean, undistorted sound. The subtle (and not so subtle) harmonic distortion and tape compression that results from over-recording can’t be recreated by overdriving the record input of your DAW; digital distortion is unusable and undesirable.

Many classic 1960s hits, especially American soul tracks by Aretha Franklin, Otis Redding and so on, featured a ‘hot’ vocal sound that added an exciting edge to the loudest parts. Nowadays, the effect can be emulated with plug-ins as well as hardware units. Top of the tree for analogue saturation is Thermionic Culture’s Culture Vulture, an all-valve distortion unit that gives a wonderfully warm, musical saturation in triode mode and a more aggressive, odd-harmonic distortion when switched to pentode.

Switching to solid-state, Warm Audio’s Tone Beast is a fully-featured mic preamp with a wide range of tonal options, including some authentic vintage flavours. It also features a saturation control that offers musically convincing overload, to mimic the exciting, hot sound of burning to analogue tape – a worthwhile addition to any digital setup.

Stereo kit

Recording drums in mono might be a step too far for many, so adding a second overhead mic would enable a stereo image to be created. Towards the end of the 1960s, engineers began seeing stereo recording as the norm, largely due to the introduction of eight-track recording in the UK during 1968. An early three-mic stereo drum-recording technique was invented by Glyn Johns, who used it to record classic late-60s/early-70s albums by The Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin.

The Glyn Johns technique has been well documented; however, not all descriptions of it are accurate, so it’s worth retelling with input from the man himself: “The principle behind it is that it allows the drummer to express his own dynamics in what he’s playing,” explains Johns. “At the same time, the idea is to capture the sound that’s unique to him, as all great drummers tune their kits in their own particular way.”

Johns used two large-diaphragm condenser mics set to cardioid to capture the kit in stereo, along with a dedicated bass-drum mic. The first condenser mic would be placed approximately three feet above the kit, pointing at the gap between the rack tom and snare drum (not directly above the centre of the snare drum, as is often erroneously stated); while the second would be positioned on a small stand, around three feet from the ground, to the side of the floor tom.

This mic would be angled so that it was looking at both the floor tom and snare drum. Each of these mics would be equidistant to the snare drum, so that the snare remained in the centre of the stereo image when panned. Johns rarely panned these two mics more than 50 per cent: however, a wider stereo image can be obtained with more extreme panning. Many engineers, when employing this technique, go to great lengths to position these two mics exactly equidistant to the snare, but Johns adopted the preferable method of using his ears.

In his autobiography Sound Man, he stated: “Contrary to poplar belief, I have never used a tape measure. It’s not that precise, it is just a matter of using common sense and believing it will work, making small adjustments depending on the kit, the balance the drummer is giving you and what he is playing.”

Wall of sound

Phil Spector’s legendary ‘Wall Of Sound’ is instantly recognisable. Classic early 60s hits such as The Crystals’ Da Doo Ron Ron and The Ronettes’ Be My Baby epitomise what Spector called “little symphonies for the kids”. Recorded at his favourite studio, Gold Star, a key element of the sound was Spector’s method of using multiple musicians playing the same part to produce a dense, weighty backing track.

Employing as many as five guitarists, three or four people on pianos and two bass players, along with drums, percussion, strings and horns, the ensemble’s thick and meaty sound would then be sent to Gold Star’s wonderful-sounding echo chamber to make the sound bigger still. Spector liked to blend the vocals deep within his dense backing track rather than mixing them out front, as was more conventional at the time.

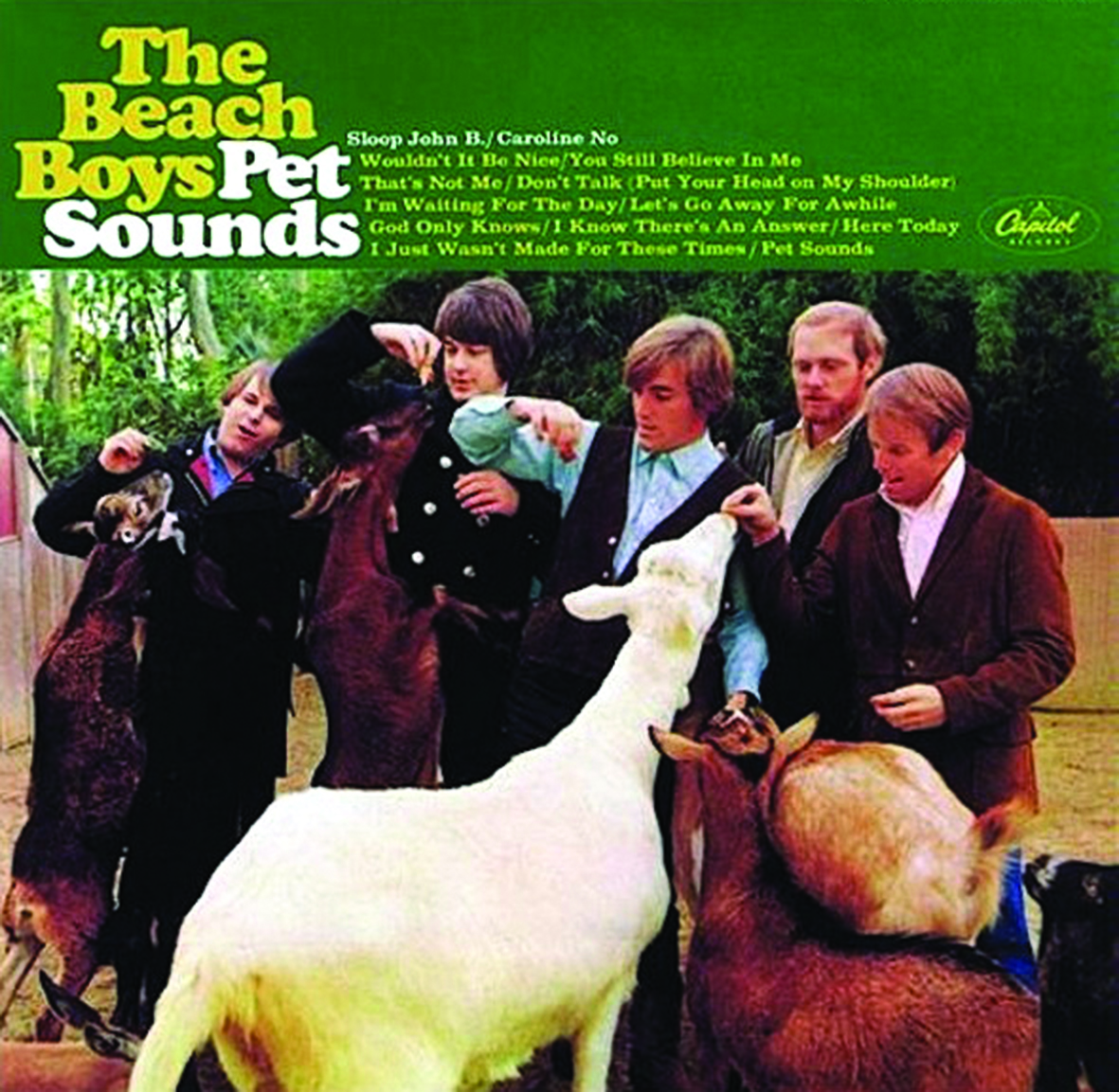

The Wall Of Sound was a huge influence on The Beach Boys’ genius composer and producer Brian Wilson. He also used Gold Star studios, along with many of the musicians Spector employed and the results can be heard on the classic 1966 Pet Sounds album and also his masterpiece from the same year, Good Vibrations.

Although the Wall Of Sound relied on many musicians playing in unison, today’s unlimited track counts allows multiple overdubs to simulate the sound. Roy Wood of Wizzard used multi-track to create his 1973 chart-topping homage to Spector, See My Baby Jive, and also their perennial Christmas hit.

The Motown sound

The ‘keep it simple’ approach was also key to the instantly recognisable Tamla Motown sound that graced so many hits by artists such as Marvin Gaye, Smokey Robinson and Stevie Wonder, as well as groups such as The Temptations, The Supremes and The Four Tops.

‘Hitsville USA’, as Motown’s HQ was nicknamed, churned out dozens of pop/soul classics throughout the 1960s and beyond, all featuring the work of the legendary Funk Brothers, a team of ace session musicians often including the superb rhythm section of James Jamerson on bass and either Benny ‘Papa Zita’ Benjamin or Richard ‘Pistol’ Allen on drums. Allen recalls putting electrical tape on the snares on the bottom of his drum, to keep them close to the resonant head and produce a crisp sound. The mic used to pick up the snare and hi-hats would also be used to capture the ubiquitous Tamla tambourine.

Motown engineers often used Pultec equalisers to brighten up recordings and create their trademark treble-heavy sound, designed to have presence on AM radio. Pultec’s EQP-1A was capable of doing what has become known as the Pultec ‘low-end-trick’, a method of simultaneously boosting and cutting at one of the unit’s selectable bass frequencies. As the boost and cut curves did not share the same characteristics, the result was a boost in the useful bass frequencies combined with a midrange droop, which created space for lead vocals to sit nicely in the mix.

This method of EQ’ing whole backing tracks has fallen out of favour in modern times, as engineers focus on tweaking individual channels. However, this technique is useful when trying to recreate vintage sounds. Just as mix-buss compression can provide a certain amount of ‘glue’, mix-buss EQ can help achieve the tight, punchy and cohesive sound reminiscent of many 60s pops hits.

Securing an EQP-1A-type equaliser is no longer the expensive business it once was, before pro-audio makers began revisiting designs from pop’s illustrious past. The design has been reissued endlessly in recent times, both as an authentic replica and a feature of other equalisers and channel strips. My personal recommendation for a superb-sounding, affordable hardware example would be Warm Audio’s brilliant EQP-WA; read a review of it on MT’s website.

Next time we’re moving to Memphis and the great soul singers, the maverick sounds of legendary producer Joe Meek and The Beatles transition in sound with the arrival TG12345.