Petri Alanko – A Video Gaming Music Guru Reveals All

We gave you a short interview with Petri Alanko a few months back, but so good were his answers, we felt it was scandalous to only offer you a fraction of what he told us. Here then, is literally EVERYTHING you ever wanted to know about scoring for video games in one of the most […]

We gave you a short interview with Petri Alanko a few months back, but so good were his answers, we felt it was scandalous to only offer you a fraction of what he told us. Here then, is literally EVERYTHING you ever wanted to know about scoring for video games in one of the most revealing interviews we have ever conducted…

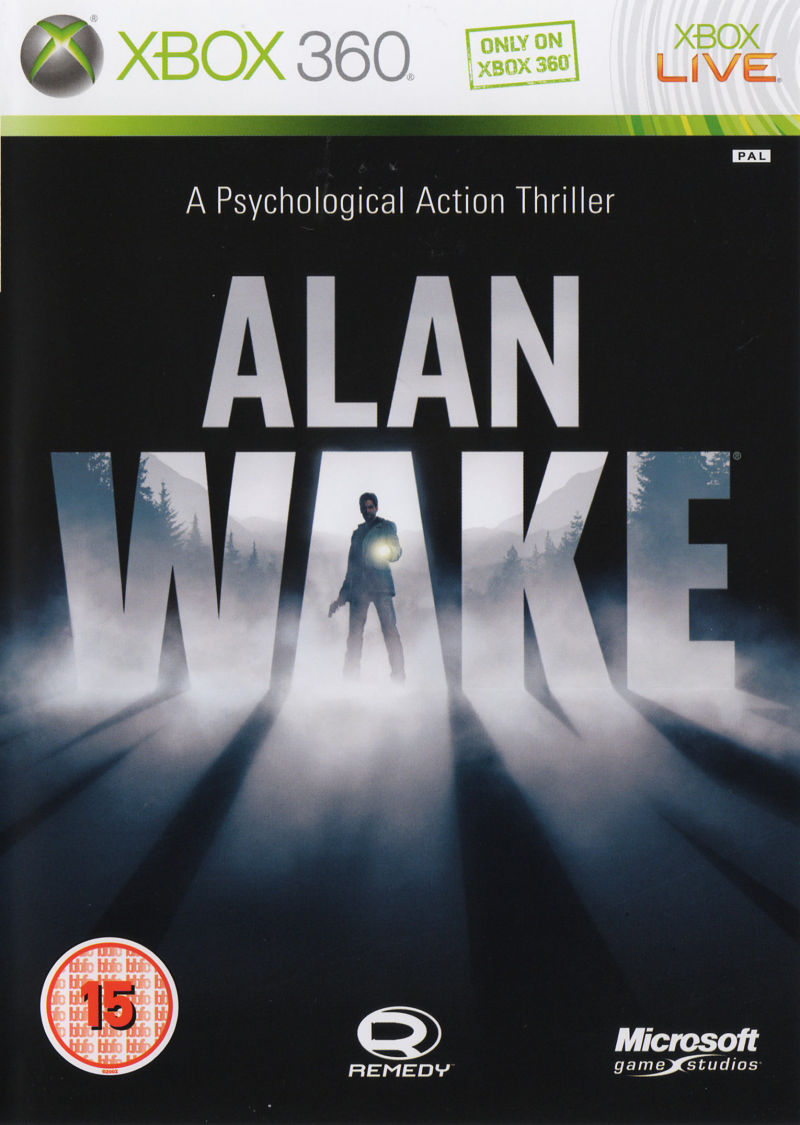

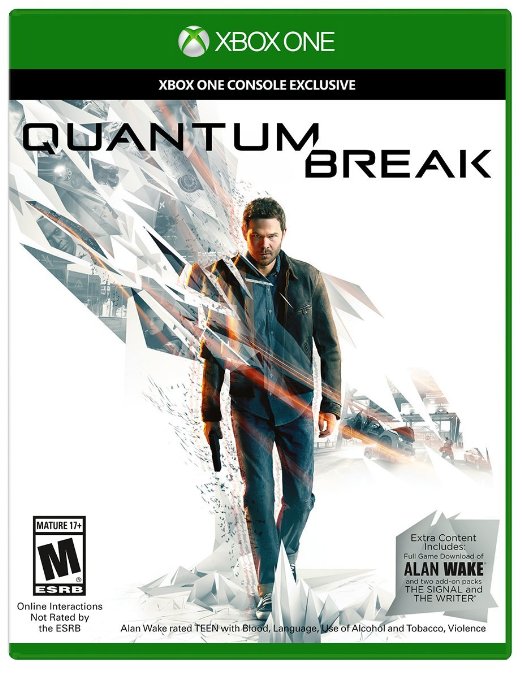

Petri Alanko is one of the most colourful characters in video-game music production, with a healthy perspective on his craft. As we discovered a few issues back, he is a prolific composer and has scored video games including Alan Wake and Quantum Break.

He has also performed with the Helsinki Philharmonic Orchestra, and released music across countless genres. We didn’t have nearly enough room to get geeky with him last time around as he uses some extraordinary gear and processes in his productions.

This, then, is Petri Alanko Part 2: The Geek Edit! So, a warning: this gets deep, but it’s also one of the most revealing features we have ever run for MusicTech – you WILL learn a lot about the art of video-game music production.

MusicTech: How did you discover you had musical leanings?

Petri Alanko: My grandmother and I were visiting an acquaintance of hers who owned a nice collection of vinyl, mostly classical.

A Maria Callas album was on, and as La Callas hit the high notes I tried to reach them with a piano next to the turntable. I hit the correct note and kept pounding the key down and when the diva descended down, I traced those notes, too.

My grandmother’s friend apparently urged my family to get me some ‘professional help’, and they were first rather shocked, until they realised ‘a music education’ would’ve been a bit more appropriate and less worrying way to put it!

Anyway, soon after that, they took me to piano lessons. I loved playing the piano right from the start. I loved taking the information in. I was five then. My purely classical education received a serious dent when I heard Kraftwerk’s The Robots on the radio.

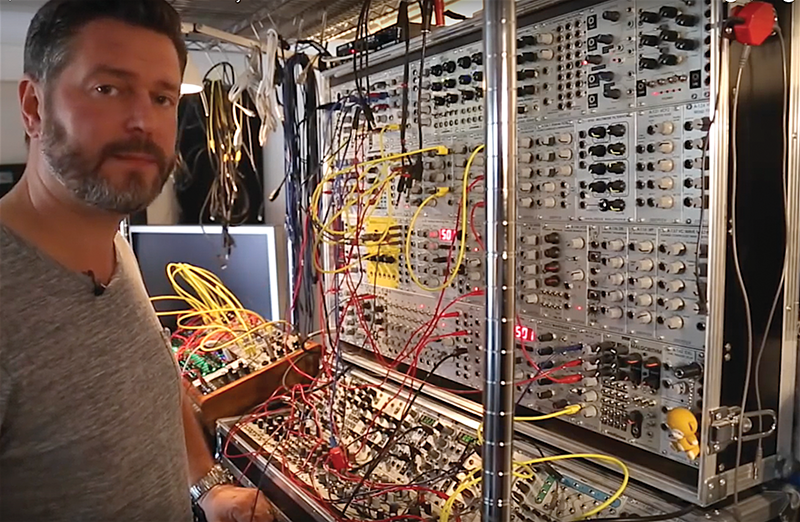

The Macbeth M5 Modular synth – the tip of the Alanko Gear iceberg

Mother told me later she could see I was mortified, frozen: I just stared at the radio when the bassline began, and my little feet started picking the beat, and when the vocoded vocals came on, I stared at my mother, my eyes wide open, full of enthusiasm and questions – now what the hell was THAT? I picked up a word from the DJ’s babbling, it was ‘synthesiser’.

The very next day, we visited the music library in my hometown in Finland and tried to find out as much about synthesisers as we possibly could, which was practically zero.

Then, a short while later, a book written in Finnish, Osmo Lindeman’s Elektroninen Musiikki was published. I think I tore it to pieces by just reading it. Something from the book’s avant-garde attitude echoes in me, even today.

The classical repertoire was pushed slightly away, and my world was filled with Jean-Michel Jarre, Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze, Kraftwerk, Isao Tomita and the post-punk new-wave bands with their rock attitude and synths. Gary Numan was and IS awesome. David Bowie wasn’t exactly a synth hero, but definitely my hero.

Then came Ultravox, Soft Cell, New Order, OMD, Duran Duran, Depeche Mode, Japan, John Foxx and lots of others. Pretty soon after my first Kraftwerk dose, I knew I wanted a synthesiser, and I saved and saved to get a second-hand synth – a Roland SH-5, from a friend of a friend of my father’s.

We sold our Yamaha electronic organ to get a Roland Juno-6 and a guitar amp. I connected both synths to it via a Y-lead, and with certain settings, the sound was rather good – and some settings provided lots of saturation and distortion. The leftover money went on a Boss DR-55 drum machine. It was all really nice.

My gear lust pretty soon got out of hand. At some point, after having moved out of my parents’ house, I had a huge modular System-100m and SH-101, MC-202 and Yamaha CS-30 and CS-15 synths, Korg Wavestation, Korg M1R EX, Cheetah MS6, Yamaha TX16W and Ensoniq Mirage samplers, Roland cheapo digi-sequencers (both MSQ and CSQ stuff, for modular and MIDI machines)… among other instruments.

But no food in the fridge, not even a light – so I had to go work in a music shop to get some money and continue my stumbling university studies.

One day, a guy walked in and we started talking about music and he offered me a job – production and songwriting. He had a studio, I had lots of synths, so after 20 minutes, I quit the shop! I ended up gigging a lot. I did some big gigs to 20,000-plus people in Finland.

My involvement with mainstream pop songwriting and the dance genre continued until the late 90s and early 2000s, which is when I was introduced to the Helsinki clubbing scene.

That led me even further into the trance and club scene and, with quite a few lucky coincidences, brought me in contact with DJ Orkidea, with whom I’ve been collaborating a lot on his albums Metaverse, 20 and Harmonia among several remixes.

I was lucky to meet the trance duo Slusnik Luna, with whom I collaborated and some of those people eventually began working with gaming companies and other new-media industries.

Subsequently, after my name had been circulating around for a while, the gigs started to appear more frequently and then, one day, came the call that changed my life forever: ‘Hello, this is Petri Järvilehto from Remedy Entertainment…got a minute?’ They needed a composer.

MT: Describe your ‘sound’?

PA: I think it’s a mixture of my youth favourites, the synth gods, spliced with my obsession with indie rock – how most of them treat harmonies and melodic lines rings a bell from the post-new wave bands of the 80s and the synth pop groups.

There are some flavours and influences from various composers, a diverse bunch of styles: Satie, Pierné, Bartók, Reich, Glass. Somehow, I’ve managed to melt them into something recognisable as ‘me’, or at least that’s what my clients and friends say.

Petri’s SE-1X, ARP Odyssey and SE Omega 8

Towards the end of my teenage years and early adulthood, I was totally taken by acid, house, techno, the whole rave culture: they share one thing: energy and how to administer it.

Speaking of which: I tend to use a huge amount of dynamics within a song and lately, as I’ve tried to make more open mixes, the dynamics matter even more – and while the dynamics are there, so are the frequencies, too.

I’m not afraid of using the whole spectrum as long as the individual tracks are carefully carved: if a tracks needs to have an HPF, I’ll put it there.

MT: How do you define the role of game music composer?

PA: I’d like to think my duty with Quantum Break was to carry the story, to make it meander and flow as events unfold; the screenplay connected with me immediately, and I felt I had lots of room to play with.

Of course, it’s not action-action-action all the time. Allowing some breathing space makes everything more human and approachable.

The wonderful Alan Wake – a game that’s occasionally terrifying, often funny and sonically rivetting

I treated characters in Alan Wake and Quantum Break as real people, as if they were alive, with a believable history and story.

I’m willing to say those two long-term projects have affected me more than anything else in my music career, and each note, each second in them is exactly how I wanted them to be in the first place.

Alan Wake was my first big calling card, and it brought me a lot of work in the years since, and its soundtrack, again, was very carefully put together.

Sometimes the composer has to introduce the player to something that hasn’t even arrived yet, to alter his/her moods and modes into what’s upcoming, and it’s a bit mesmerising, really – you’re playing with the emotions and the feelings sometimes before the exact reason is there.

Quantum Break took the player (and Petri) to a whole new level

I’m not saying this is for games only; the same applies to movies as well, but controlling it in a tightly set game-audio playback system makes it even more challenging due to the modular nature of game music.

In short, my job is to support the story, naturally, but I must do it so that the player connects with those the emotions, appreciating the past and the future at the same time.

MT: What special challenges do you think that game-music producers have over, say, film or TV composers?

PA: Oh, the modularity, that’s for sure! It’s something film/TV people never encounter and one could say they’re lucky that way: they just score to the picture, and they’re happy ever after.

TV and movies are linear media: nothing ever changes, the DVD stays the same all the way to the umpteenth viewing, whereas with some luck, some games can never be played exactly in the same way.

Dynamic-versus-linear creates some challenges, yes, but the current playback engines (WWise and FMOD being the most popular) offer some modularity, and are able to alter the playback according to onscreen actions and the player’s decisions.

I feel pity for the audio integrators who have to deal with those issues. I could do it myself, too, but the UIs of both FMOD and WWise leave much to be desired, in my opinion.

They have more in common with engineering rather than music – it should all be about emotions and feelings, there’s very little room for exciting the creative flow.

Even the smallest interruptions can affect the quality and each workflow stumble seriously slows you down.

What most of us game composers have developed is an understanding, a conception of the whole picture.

Petri’s DX7 Centennial

Because of the modular nature of game music, composers need to have a ‘memory print’

of what they’re doing and I picture mine as a 3D field rather than a linear line (i.e. dynamic/modular versus linear media), a bit like having a huge layered Excel sheet in your mind and you’re thinking: ‘this stem part fits with a1p3, this with a3p2’ and so on.

The more there are of those natural-sounding transitions, the better the results.

Also, I noticed towards the end of Quantum Break soundtrack that I was able to totally detach myself from the surrounding world.

A bookshelf collapsed next to me and I didn’t notice it. I had no headphones on and the listening volume wasn’t spectacular, but the intense concentration locked the outside world away.

That’s something I’ve developed throughout the past 10 or so years, and it allows me to work under difficult circumstances.

Another challenge, by the way, is the huge amount of data produced during a, say, four-plus-year-long development phase.

Hard drives are oozing data after a short while and all the iterations and multiple versions and stem files plus all the audio library data… If you’re not careful, it’ll drive you crazy.

A two-hour movie could have two hours of music at most, whereas a game’s play-through time could be 13, 16, 20, even 40 hours or so. A lot of music and audio assets are required, and the number has been increasing throughout the past years.

For instance, in Alan Wake I wrote 243 minutes of music, in Quantum Break, we had exceeded that amount already in early 2013. I really have no idea how much there is, but… it’s a lot! And backups. And the backup of backups, too.

MT: How does the studio technology help overcome these challenges? [Get ready gear geeks MusicTech Ed]…

PA: In every case, I create a library of sounds from scratch for the project, something that’s unique for that particular project only and never recycled with others.

The longer I can spend with the library/sound design process, the better the final outcome, the clearer the fingerprint.

I’d love to think I’m a fine-arts carpenter rather than some guy putting together an IKEA chair with an IKEA key.

One has to have a craftsman’s pride: this is mine, I did this, I did this really well. Music and production must have substance to live and to gain the longevity I’m always after, and I’m willing to invest a lot of time, effort and love into achieving it.

Also, creating a smooth workflow helps a lot. It pays off to hone your libraries and start-up templates into a top-notch condition.

Sometimes, when watching a cinematic for the first time, I’ll write some memos, mark down important time stamps, and sometimes triangulate (or estimate) the tempos and meters with an SMPTE calculator, or do it by ear.

I prefer trusting my ear for timing and tuning as well as possible speed up/slow down passages. Sometimes, I record a click track by just clicking my fingers – I’m really old school that way. I’ve gotten into this habit of closing my eyes and ‘seeing’ a grid of tune or time, and trusting it.

However, where technology really helps is with the sound libraries and software instruments.

Now, since I’m a bit of a geek thanks to my theoretical physics background, I love using all sorts of esoteric plug-ins and hardware, and it’s no secret I’m totally in love with Reaktor and Kyma – and while the processor speeds have gone up, my Kyma usage has somewhat decreased, but there are some things it can do so incredibly well – and some things only Kyma can do.

During the production of Quantum Break, I created about 550 to 600 presets for Logic, both channel and instrument settings that were tied to a particular person or event, location or action.

That was something that really enabled me to conquer the tight schedules, but despite the preset settings, some adjustments were done in each cue. Also, using huge start-up templates provided me enough room to do just about anything with the instrumentation.

These were great, but nasty to load. Sometimes, my Macs were literally frozen when they kept loading the start-ups.

I had several different templates for certain events and different persons, each containing a suitable set of sounds and plug-ins. Also, each synth had its own categories for different uses. This meant a lot of bookkeeping.”

MT: Is there any gear that lends itself specifically to game production?

PA: I can’t exactly put my finger on why, but my Korg MS-20 has been used more for game projects than regular music.

Although it’s a very simple synth, very approachable, there’s a certain playful colour in its voice and I can’t really take the machine seriously, no matter how hard it’s screeching.

It’s a chihuahua, sort of. To be honest, I wouldn’t have my smaller setup at all if I wasn’t involved with the gaming industry.

It’s really easy to take a facsimile of your larger setup with slightly less ‘oomph’ to a client and do a few sketches and drafts there, some sound design, et cetera.

I don’t really separate my gear as ‘this and that’ and I don’t really separate the projects, either. If I’m doing music for games, it’s a serious business… it’s really got to sound great if some 100-plus million people are going to hear your handiwork.

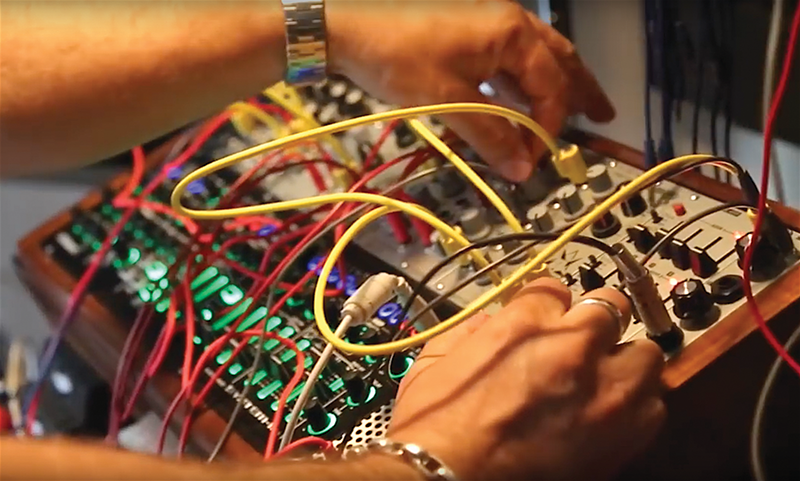

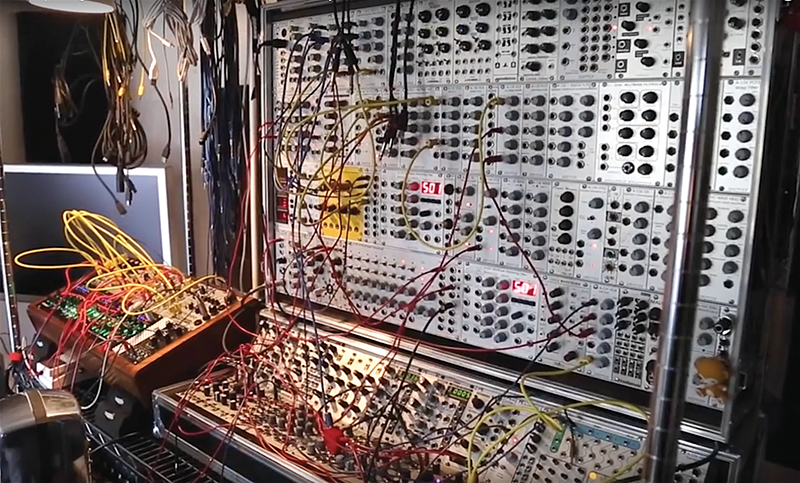

MT: Tell us more about your modular synth setup…

PA: I’m using Expert Sleepers’ hardware and software and it’s phenomenal – really, really good! It was involved in everything [on Quantum Break]. I know it through and through and the machine functions really well as an entity or as a divided instrument.

I would say the majority of the tracks recorded went through it at some point during the soundtrack’s development.

I started each cue as a totally plug-in project file, and the first to go were Logic’s internal plug-ins in most cases (excluding Space Designer and Alchemy).

When I was sure about the structure and the pieces needed, I started replacing them with Mörkö (modular) and my other equipment. Sometimes, it went the other way, as I ended up replacing my Matrix-12 tracks with Arturia’s Matrix plug-in.

Each external synth got a bit of love from Neve preamps or whatnot. The idea was to smear and smudge the sound a little bit during the tracking phase of each song – not to overly destroy, just give it a hint of character – but if you’re careless, you’ll end up with a wall of distortion.

I’m a big fan of saturation and harmonic distortion, tape machines, analogue delays and so on. I think this dates back to my early days with synths.

As a controller, I’m using an old CME UF80, Haken Continuum and ROLI Seaboard. And four iPads.

The modular synth sits in here always, so it’s more or less a regular in each production, but I’m using it for various tasks,not only as an instrument but as an effect/processing monster, too. Its name, Mörkö – a bogeyman – tells all.

“Right now, it’s got about 16 VCOs and at least the same amount of different character VCFs. For VCAs, I’m using Intellijel stuff, but some other low-end ones as well – I think there’s no room for hi-fi snobbery here.”

Petri’s Roland AIRA System-1M and Doepfer modules

MT: Which soundtracks do you admire by other composers and why?

PA: Something that moved me thoroughly was Interstellar. That was a brilliant piece of music as a whole, and how the music was used in the movie.

There are scores from other modern composers: Cliff Martinez’s Solaris and Contagion, Reznor-Ross’s Gone Girl, Sakamoto’s The Revenant – oh gods, that’s one nice piece of art, and as a young boy, I liked his Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence score a lot. Tangerine Dream’s The Sorcerer was a turning point when it came out.

What’s common for those I mentioned seems to be this –‘low-key emotional stream’ that bursts out every now and then and throws everything at you in a way you can’t really avoid.

Now that I’ve mentioned movies, I must add the exact point when I started to believe in quality game soundtracks – when Quake featured Reznor’s score. It really made me think about my possible career moves, but the game industry’s quantum leaps were still years to come.

It seems there’s something in fearlessness that moves me. Each aforementioned piece of art was really that: fearless, like a figurative middle finger to otherwise bland movie (and game) scores.

I tend to dislike the usual ‘let’s underline the action with war elephant drum squadron and spiccato low strings and BRAAAAAHM too’ approach. It’s more noise or sound effects than music, actually, and leaves me a bit cold. And it doesn’t really move me emotionally, without a picture, if even then.

MT: Do you have a stance on studio technology: old versus new, analogue versus digital?

PA: I’m using a lot of old-ish gear, but I’m not an analogue devotee. I do what it takes to get the sound in my head, and I’m not stubborn in analogue-synth ways.

Petri’s modular setup

Sometimes, people get really mixed up with what they’re hearing – such as when something they’ve thought of as being an analogue synth is actually something quite different.

It’s not too long ago, when a bass sound I used was described as a fat analogue sound reminiscent of a MiniMoog and it was done on a DX7, recorded through a set of Neve EQ and preamp.

For Quantum Break, I recorded a lot of stringed instruments played by numerous different vibrating instruments, Lego motors, nail files, rasp, toothbrushes, sand paper – lots of different stuff.

The cello and acoustic guitar were especially generous and flexible tonally. I used a lot of that material as a basis for my pads and some really odd effects.

For instance, I separated the noise and tonal components from each other using iZotope RX, and combined them later in Kontakt or Reaktor; for the latter, I used grain-cloud oscillators and the results were very acoustic-sounding, yet they had a certain unknown vibe to them.

I take multi-sampling very seriously, and I tend to use many randomly cycling keygroups to provide enough variations so that the results keep their unexpected, ‘natural’ complexity. Nothing’s worse

than a machine-gun effect with too few samples, it’s repetitious and boring.

I think it comes down to harmony, voicing, myriads of layers, movement and bespoke libraries that define my sound.

None of those is actually easily explainable as some things, I just… do. Naturally, without even thinking, really. In the studio, I’m totally immersed all the time, and it sometimes worries me a bit, since I see or hear nothing. Hours disappear.

MT: Talk us through the main components of your studio…

PA: It was formed when I bought the house I live in. It’s nothing fancy: a utility room, not a showroom and I rarely bring clients here.

If you’re stepping through my door, you’re considered as a friend. So, my three Macs work in conjunction: the large system has two UAD Apollos chained together, the smaller setup that I sometimes take to the client’s office has one Apollo. Both systems have identical drive systems, RAIDs and libraries, and they’re mirrored once per day.

Petri has recently migrated to Cubase from Logic 9

The larger setup has currently three displays, one 4K, two ‘normal’, the smaller has one 4K display. I would consider those plus my speaker systems as ‘the main components’ and everything else (synths, outboard) as extra.

The main room isn’t too large, and I’m not a fan of recording rooms or vocal booths, never have been. For pop productions, I’ve recorded all vocals in the control room and never had problems with spillage or leaks.

Sometimes, when a vocalist has had trouble expressing the emotions, I’ve held his or her hand to provide physical feedback and I can heartily recommend that.

For taming the reflections, I’ve got a few curved portable booths that I place behind the mics during tracking. I like to keep things simple and uncomplicated

All gear is interfaced through the Apollos, ethernet, lightpipe and via the Neve 8816 summing mixer, and I’ve had no clocking trouble or other issues since putting this together.

In the storage room there are my Sub 37, Minimoog Voyager… er, Studio Electronics Omega 8, along with DX7 Centennial, Korg MS-20. My father grabbed back my Yamaha electronic organ, a three-manual D-85, and my Macbeth is causing me a bit of grey hair.

MT: Tell us a bit more about that three-Mac setup…

PA: There’s a fully loaded Mac Pro as a master, another identical as a slave, plus a MacBook Pro as a spare one, all connected via lightpipe and ethernet (and Vienna Ensemble Pro).

There were a few cues where all three machines were used, just in case, but I don’t think I maxed anything out, not even close.

If I had used 5.1 or 7.1 all the time, that surely would’ve happened, but luckily, only stereo stems were needed.

However, there are 5.1 mixes of each important cue and some 7.1 as well for a select few.

MT: You were a big Logic fan… but not any more?

PA: When I started receiving the first, more advanced cinematic drafts, I placed markers on the timeline, locked them, and begun fiddling with Logic X’s tempo and metering – and to my surprise, this pretty much confirmed what I had done by ear in the first place.

However, making the shift from Logic 9 into Logic X compromised some of the workflow, and I still think that the Apple guys are really inventing some of the stuff just to annoy us… Now that the latest update arrived, they changed the toolkit shortcuts.

It is he who decides whether Alanko’s output is acceptable

Why do they insist on constantly messing with my system? At least give us the option to eliminate it myself… and give us the freely selectable colour palette back!

Although I had been an avid Logic fan for, well, forever, actually, since version 1 when there were no audio capabilities, I decided to jump the Logic train and check out Cubase.

I used it before moving over to Notator SL back in the Atari days, and I’ve heard lots of love from surprising sources about Cubase’s development and dedication to listen to their user base.

It’ll take some time to be as quick as I was with Logic 9, but I’m known for putting myself into difficult situations, changing from right-handed to leftie, disabling plug-ins and forcing my brain to compensate the missing tools with others. Hocus pocus for some, venting brains for me.

MT: Can you tell us a little about your signal chain?

PA: Pretty much all channels had a Neve EQ insert somewhere, and most of the things were recorded through a Neve preamp/EQ.

In the beginning, I had some marvellous 8086 series input channels modified and racked (I used them as summing channels), but since they were from an old mixer frame, and the original owner was a bit carefree, they weren’t exactly in the best possible condition so I decided to sell them back to where they came from.

Spending about 1,000 Euros each year just to maintain the thing? No thanks. So, I got rid of it and acquired a Neve Summing Mixer (8816) to do the job, and I’ve been happy ever since.

Everything had to be more or less recallable quite easily, so the first year into the project involved a lot of honing and tweaking the workflow.”

MT: And dare we ask, what about plug-ins?

PA: I think I’ve got enough plug-ins for a few lifetimes, so don’t get me started – but there are a few things I really, really love: Zynaptiq, DMG Audio, iZotope, Valhalla DSP, Audio Damage… and I’ve used numerous Kontakt 5 and Reaktor 5 plug-ins. Instrument-wise, U-He’s synth plug-ins were heavily prominent everywhere.

Madrona Labs and Glitchmachines were also here and there – and iZotope’s Iris 2. I used BreakTweaker for some funny basslines, but it was a bit of a bitch to program to do tonal and harmonic stuff (it could use an overhaul and thus sell more).

And with Plogue Bidule, I was able to use my trusty old Neuron VS! I tend to ‘abuse’ both the plug-ins and the synths.

MT: What about your monitoring setup?

PA: I’m currently using a two-speaker setup system in my studio, a pair of Genelec 8260A speakers and Amphion’s One12 – and if needed, I’ve got a Genelec G Two and sub 5.1 system and quite a few others in the storage room, too, but the Finns seem to make the best systems so far.

I go through each track one by one with 8260s and, especially with a large amount of tracks – say, 200 and over – I’ll turn to Amphions.

They’ve got that NS10 vibe to them, but their frequency response is a lot more humane. I used to have a phase when I did the final mixes on a pair of 1999-ish Sony multimedia speakers that I bought for 8.41 Euros… for a pair!

And our successful KLF remix was balanced with them, so never underestimate the power of cheap crap. There’s no price in creativity, so why NOT use cheap crap?

MT: What is on your wishlist, studio wise?

PA: Hmm. More space and a DSI Oberheim OB-6 would be nice. I’m not lusting over any antique compressors or EQs or mixing consoles, I’ve tried that game already, so I’ve lost my appetite.

However, I’m constantly reaching for a tighter workflow and have spent a lot of effort and resources into getting things rolling. I’m hoping to find people able to code stuff, so I could make a part of my software-based workflow slightly more fluid.

Oh, and I’d love to get myself a Synclavier, as I’m a fan of resynthesis and FM. I’ve been close to ordering one of the refurbished systems, but my sanity has always won. They aren’t exactly the quietest systems I’ve heard, and the interfacing isn’t the smoothest.

But, if they ever come across with a machine that’s in a rack and interfacing is done via a regular AU plug-in, data through Thunderbolt, then I’m all in.

It’s safe to say that’s never going to happen – timpani roll – or is it? Some of my work is heavily affected by different file formats, not just audio or video, but also application-wise.

Now, OMF and AAF don’t really work, but pretty much all software companies in the DAW business seem to have a similar way to treat their project files: there are audio tracks, there are instrument tracks, there are buses and sends and outputs and inputs.

Now, we’ll soon be able to put a man on Mars and brains and lungs have been transplanted to a living human being, but we still don’t have an interchangeable file format for audio projects, with inserts and sends and automation.

I’ve tested some ‘converter’ software for different DAW platforms, but they more or less feel like no-thank-you. A lot of fuss. How hard can it be?

MT: What about some of your sound sculpting and editing – you must do a lot of sound design?

PA: I used Melodyne to make tonal sounds slightly more uneasy at times (emphasis on the word ‘slightly’), pitching the higher harmonics more and more off.

Sometimes, I just killed the tuning changes of a few upper harmonics to add some artificial-like steadiness to, say, strings or piano-based effects.

Revoicing the ringing reverb tails, for instance, to keep the space, but to avoid the dissonances. I did that also in real time with PitchMap.

Pretty much each noise atmosphere I used got some love from PitchMap, as it’s really easy to round a few frequencies to a certain note pitch, to provide just a bit of order in the chaos.

I also built a nice small string section pad, where each note had one very lightly played, almost whispering violin/viola/cello and the starting point was randomised each time the key went down – nothing spectacular there, just a string pad – but combined with just about any synthetic pad-like sound, it provided a mysterious amount of movement and life to an otherwise dull sound, as long as the components were at an equal volume.

If the synth pad lived too much, I’d put a Waves Vocal Rider on the string channel. It’s a matter of abusing your plug-ins…

Oh, this deserves a special mention: at some point, I knew Toto’s Africa would start playing during a scene, so I started morphing the piano ostinato into the Africa intro drum loop with Zynaptiq’s Morph 2.0; the cue was in the same key and tempo.

Unfortunately, I’m not yet far enough in Quantum Break to find out whether my trick was implemented or ditched. The Morph 2.0 plug-in was used heavily elsewhere, too, but its role wasn’t that obvious.

MT: That’s an amazing insight – what other tricks can you reveal?

PA: I think it all begins with layers, really – simple layers with slow movement that’s under control. I like controlled randomisation, something I’d like to call ‘humanisation’, not overly exaggerated, zero-to-100-per-cent stuff.

I very seldom use any choruses or ensemble effects; sometimes, I’ll add something from Eventide to provide some smooth-pitch randomisation, but my time with heavy choruses ran out in 1982, when chorus setting II was 24/7/365 on my Juno-6, I think.

I’m usually putting each layer through its own convolution, used as an insert, and for Quantum Break, I recorded numerous suitable files and also incorporated material from Remedy’s audio team, who provided me with very interesting files: cracking windscreens, very tiny glass shards falling on the floor, metal canisters, etc.

I made time-corrected (or quantised) and tempo-tied versions of these, so that each layer would have this really strange-sounding, diffused, delay-like effect.

Also, I created lots of filtered white-noise burst sequences here and there, and used those as convolutions. I used Diego Stocco’s Rhythmic Convolutions and time-corrected some of those. Go and buy his Convolutions, they’re really well-executed libraries.

MT: Any specific mix plug-ins?

PA: I developed a certain master-insert habit towards the end of Quantum Break’s soundtrack mixing.

There’s always at least three tools involved: iZotope Ozone 7’s Vintage EQ, Vintage Limiter and Universal Audio Ampex ATR-102. Others will come and go, but those will stick there from now on. They remind me of my youth and gear on which I learned to develop my music.

MT: We’re nearly at the end of our interview, so how do you look back at the time you spent on the Quantum Break soundtrack?

PA: It was in the making for over four years, and there’s a lot of thought put into it. Not only thought – but all the love, hate, disappointment, anger, rage and payback as well that I could ever find within the storyline and its characters.

What appealed to me as a story was its emotional content, which was even more powerful than the action itself, and thus demanded to be told out loud.

There are the action cues, too, but the whole soundtrack is put together with much thought, and there are no fillers whatsoever. Hopefully, it should have longevity and lots of chills-down-your-spine moments to carry your thoughts away from your daily business.

Even if you don’t appreciate or play games, you can enjoy the soundtrack. A friend described it as ‘not your average date album, but boy, did I score after the last song had ended’.”

Thanks to Roland for permission to use some of the pictures in this feature.