The Flashbulb Interview – Music Creation In Seclusion

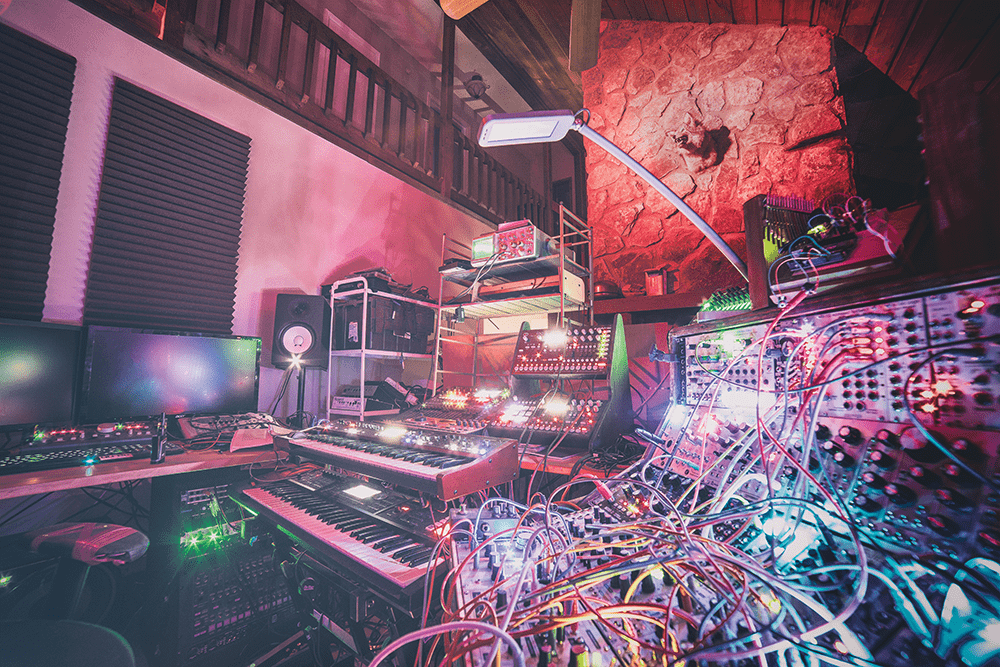

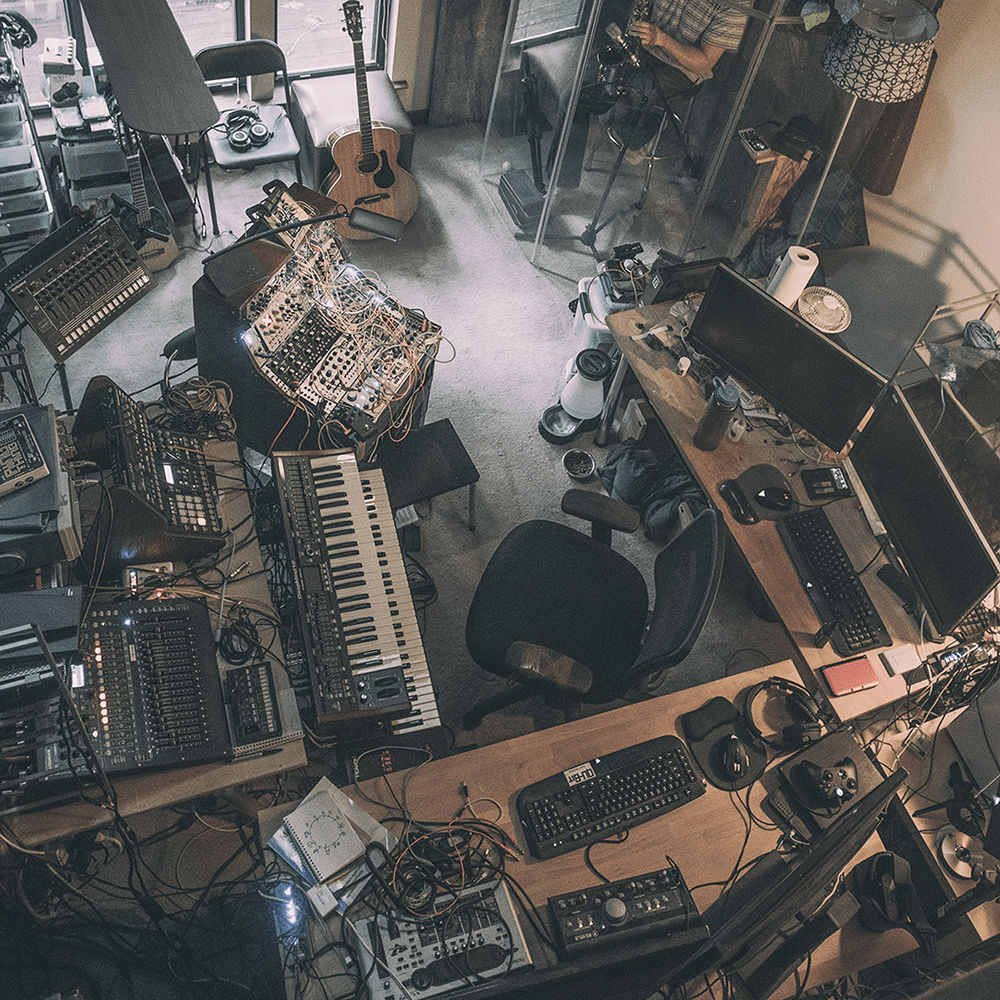

The stellar back catalogue of The Flashbulb – aka Benn Jordan – encompasses variants of jazz, IDM, glitch, ambient and modern classical. MusicTech quizzes this rarefied electronic artist in his new home in Georgia, USA…

Benn’s dog Lucy keeps a watchful eye on studio proceedings.

Raised in West Englewood, Chicago, Benn Jordan’s first introduction to music was the acoustic guitar, which, on account of his left-handedness, he taught himself to play right-handed, strung upside-down. A Boss DR-660 Dr. Rhythm drum machine piqued his interest in electronic music in the mid 90s and Jordan debuted The Flashbulb album M³ (Daily Assortment Of Sound) in 2000, while pursuing retro-acid experiments under pseudonyms including Acidwolf, FlexE and Human Action Network.

17 albums later, Jordan’s The Flashbulb project remains criminally undervalued by the electronic-music fraternity. His emotive, cinematically styled music, which blends live instrumentation with cutting-edge software and hardware-based recording techniques, has earned him a niche, yet loyal following and has led to him composing for TV, film and branding agencies.

Last year, Jordan relocated from his hometown of Chicago to the considerably more isolated environment of Smyrna, Georgia. It was in these beautiful surroundings that the concept for his latest album, Piety Of Ashes, was born, with Jordan diving into his latest fetish for MIDI-synced guitars and his own software-coded creations, based on neural-network technology and physical modelling.

MusicTech: You played guitar as a kid; were you listening to that music from an early age rather than electronic?

Benn Jordan: “My grandfather was into jazz and the first time I was actually inspired by something was when I saw Buddy Rich on The Muppet Show having a drum battle against Animal. I feel that was the basis of my percussion and where I learned rhythm from. The idea of programming that into a drum machine coincided with what was happening in the IDM scene during the late 90s.”

MT: Can you remember your gear entry point?

BJ: “As a kid, I used to go through the trash on my block to get recyclables. I told my family it was for my college fund and bought my first gear, which was a four-track recorder. The first drum machine I had was the Boss DR-660 and I still have one of those floating around. It was awesome at the time, because you could step-sequence it and go to 16th note, 32nd note and then down to a couple of hundred-per-16th note, so you’re literally going forward in hex.

“You’d get these weird tones out of it and if you did it enough, you’d actually burn the machine out. That’s what I like about modular, it has a life of its own – and I’m definitely finding the value in sequencing more than sound.”

MT: The acoustic guitar always plays a prominent role in your music. I get the impression you use it to create an emotional connection with the listener?

BJ: “Yeah, definitely, and over the years, I’ve really grown to love the sound of a steel-string guitar. That and a ronroco, which is an Argentinian instrument, are my favourite instruments to play. You hear a lot of that in my music. I’m not sure why, but it sounds so spiritual and I feel like other people get the same effect from it, too. There’s a composer called Gustavo Santaolalla, who composed everything from Brokeback Mountain to Babel. He uses one a lot and you get that same vibe; people seem to respond to it.”

MT: What approach do you adopt to electronic and acoustic recording during the creative process?

BJ: “When you’re playing an instrument, you’re doing it in real time and that’s the value of it. If you bring Ableton into a jazz trio and improvise, you can only have it play what you’ve told it to play. So it’s still driven by emotion to an extent, but it’s not live emotion. You have to plan everything, which I have no problem with – that’s a whole other side that’s very important, but acoustic instruments enable you to explore stuff melodically in real time.”

MT: Is another benefit that there’s less post-production with acoustic instruments?

BJ: “I think it’s the reverse, because I really beat myself up on recording stuff. The amount of time I go through to mic them up properly, because little tiny things can make such a big difference. When you play the guitar, you might hold the fret a millimetre too far up or down and the tuning will be one or two cents off.

“And when you mix that with a pad from a synth, you have one thing that’s imperfect and one that’s perfect, and all the imperfections that would have sounded fine acoustically suddenly sound awful. Even if an instrument’s a little bit out of tune, it can overtake the entire mix because it’s so noticeable. I’ll constantly bring any string instrument that’s monophonic, like a violin or cello, into Melodyne to nudge around and pitch-correct.”

MT: What effects pedals are you using?

BJ: “My favourite external reverbs are Mutable Instruments’ Clouds – the module – or Neunaber’s Immerse Reverberator, which they released earlier this year. I also like the Eventide H9 Harmonizer. Their Blackhole reverbs are really incredible.”

MT: You’re an accomplished bass player, too, and sound quite influenced by Squarepusher’s playing style?

BJ: “Yeah, I’ve definitely been inspired by Tom [Jenkinson] throughout my career, but what people probably don’t pick up on is that we’re both heavily inspired by Jaco Pastorius. Tom seems to have evolved into a slappy style, but if you listen to early Squarepusher and all throughout my stuff, there’s definitely homage to Pastorius. He was really the

first guy to take frets off a bass and be the virtuoso.”

MT: As with guitar, can playing live bass cause friction in a track that’s been heavily synth programmed?

BJ: “You just have more real-time options when you’re writing and it’s hard to make a synth sound funky the way you can with a bass. It can also add an organic effect to the mix. It can work in harmony, but can also work in disharmony. There are so many tracks where I’ve played bass and ended up mimicking it with synths when I didn’t like the end result.”

MT: They certainly mix well on the track Fog from your most recent album Piety Of Ashes…

BJ: “That track’s interesting because, initially, the melody was entirely a modular patch. I didn’t really like it and recorded it through a mixer onto a solid-state drive, but I remember thinking that melody could have only been written using a bunch of random signals going through logic gates and switches. It ended up being one of my favourite patch recordings to listen to, and I ended up complementing it with bass and live drums.”

MT: Piety Of Ashes has quite an ominous title and artwork, but the music is pretty downtempo. Do you tend to explore concepts?

BJ: “I usually have concepts and want to tell a story, and so I like to have that planned out within the first couple of tracks, as a guide. I also like to give myself limitations, but with this one, the concept was that there absolutely was no concept and I could take as long as I wanted and spend as much money on any idea that I had – even if that was a terrible decision for my life. Unless it’s a Billboard No. 1, I’m never going to make the money back on this album, but I wanted to put everything I could into a piece of plastic and see where that took me.”

MT: That makes sense; the album sounds like you’re feeling around for a new destination between acoustic and electronic, but it’s not definitive…

BJ: “That’s awesome. The weird thing is technology played a big part in what was possible and that resulted in a lot of tracks being tossed aside or completely changed around. There was so much exploring and I was going back to things I’d recorded a year ago and refining them over and over again.

“It sounds really dark to say this, and I don’t want people taking it too literally, but I sort of look at this album as if it was a suicide note. If I were to die, this would be my headstone. If I look at things that seriously, then I’m forced to put 16 hours a day into music rather than playing video games, so it’s really, really important that everything I can offer to the world is in that.”

MT: Not all artists have such conviction…

BJ: “A lot of people forget why they make music. They forget those moments when they started out making tracks and got high off it. At some point, whether it’s through touring or getting paid for endorsements, all that gets tarnished and you lose that purity.

“I had to make a lot of decisions that weren’t necessarily smart for my living. I took two years off from playing shows, walked away from composing advertisements and moved from everything I recognised in Chicago.”

MT: Is there something to be said for the fact that once artists become financially comfortable they lose that edge, or the desire they initially had?

BJ: “Yeah, that desperation, almost. It can go either way. There are certain artists, dare I say Kanye West, where you listen to his last three releases and, to my ears, he now sounds way more creative… I also think you can get too good, if that makes any sense?

“In my generation now, I feel like everything that’s happening in my head can be made into a recording: that’s scary, because you’re no longer in a walled garden of only being able to use what you have around you. When everything is possible you don’t have any limitations to guide you.”

MT: What was behind your decision to move from Chicago to Georgia?

BJ: “My family lives downstate here and I wanted to leave Chicago, but didn’t know where I wanted to go. Georgia doesn’t really have a winter; the cost of living is cheaper and the rest I’ll find out. There’s a lot less needless stress and cost than I had in Chicago, which has the highest taxes and is the most dangerous city in the US right now.

“I’m still within a 15-minute drive of a restaurant or grocery store, but if you walk out my back door, there’s a 150-foot drop down onto a rocky cliff. My property goes onto a river and behind that is a State Park where you could literally hike for an hour-and-a-half before seeing a road. The average person would probably be pretty creeped out living here alone, especially when the coywolves start howling.”

MT: What’s your go-to source of inspiration, the computer or an acoustic instrument?

BJ: “I would say it’s pretty evenly divided between both. There’s also a lot of experimentation. Over the past five years, I’ve been really into developing my own software. While I used to be playing with plug-ins and VSTs, now I’m editing code to see what comes out the other side.”

MT: Is that because you’re frustrated with the direction software is going in?

BJ: “I think there’s a lot of amazing stuff out there right now, but a lot of it’s gone in the direction of Ableton or DJ-esque software that’s pretty far from traditional musicianship and even writing a melody the way you want to write a melody… I don’t want to shit on all software though, because a lot of what I do is about me wanting to experiment and feel accomplished for doing that. I want everything to be DIY and have my fingers in every aspect of the process.”

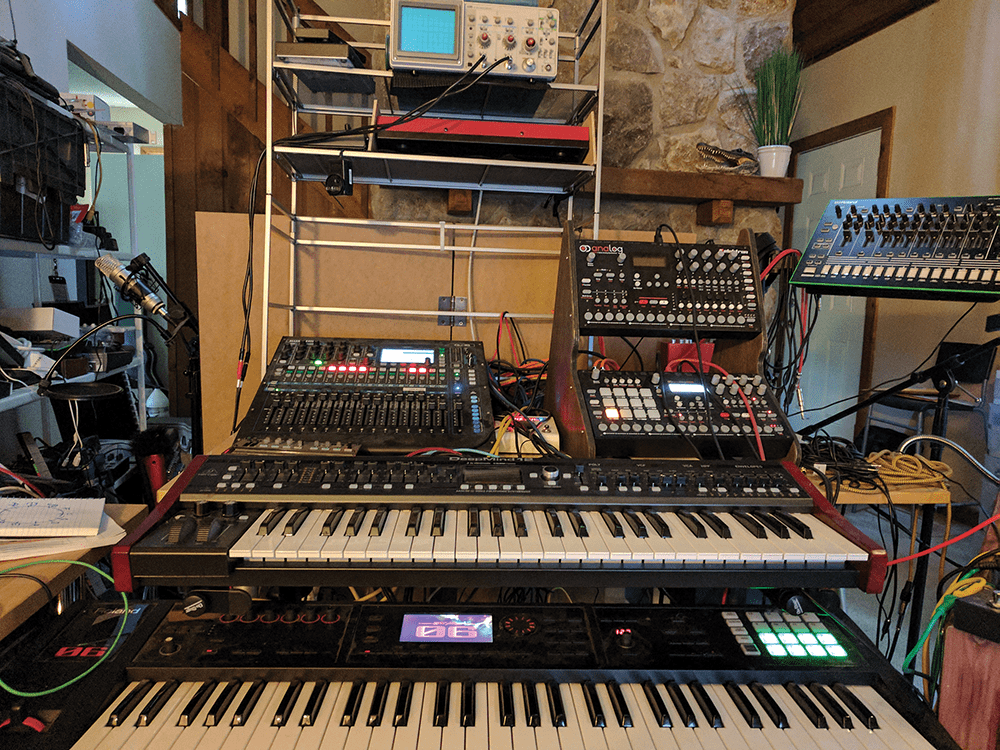

MT: Looking at your hardware synths, the Behringer DeepMind 12 and the Roland FA-06 stand out?

BJ: “The FA-06 is a classic Roland piano-roll-esque sequencer… for a semi-weighted controller, the sequencer is awesome and I use it as a MIDI controller. The Behringer DeepMind 12 is new. I grabbed it a couple of months ago and I’m making a lot of patches for it. It’s Behringer’s first synth, and for the price, you’re getting a heavy-quality 12-voice analogue polysynth, with a bunch of effects on it that are licensed from TC Electronics.”

MT: Is there any other hardware you rely on?

BJ: “I have a Nord Lead 1 that I really like. It’s so old, but the pads have a thin sound that I really dig. I also have a Korg MS2000, which I feel like I’ll never get bored of because it’s really fun to make pads with.

“In terms of drum machines, I have the Analog Rytm and the Analog Four, but I’m not that big a fan of the Octatrack – I can’t seem to get it to do what I want it to do. It’s so powerful, but it has such a weird interface. But I do like Elektron’s products and have all of the stuff they’ve released up to this year, including the Machinedrum.”

MT: What are you getting the most out of from your outboard rack these days?

BJ: “My recording interface is an RME Fireface 802 and I have an Allen & Heath Qu-16, which is entirely used for my modular setup. A lot of times, I’ll have a bunch of different outputs going into the Qu-16 and I’ll record it onto a solid-state drive, so I’m not even working with a PC at the time, it’s just recording all these individual stems. Then I’m able to bring those into a DAW and edit them.”

MT: What is it about modular that makes it a major component of your everyday creative process?

BJ: “One of the biggest attractions with analogue is not just the sound of the sequencing and the modulation, but if you take the Make Noise Maths module, for example, you can’t do anything like that on a computer. It’s kind of like an ADSR, except that it’s so tweakable.

“It has two different ADSRs in it and they can be triggered or run automatically back and forth, and you can modulate each ADSR with the other and have the outputs set as and/or, the sum of both or each one. When you play with it, it can make some of the craziest sounds you’ve ever heard just with a Sine wave. I wish something like that existed on the computer.”

MT: And are you still using FL Studio as your DAW of choice?

BJ: “Yeah, I still use it. Not on everything, but for capturing melodies. I have two computers here: one is Windows and the other is Linux. I run FL Studio on Windows with Adobe Audition for mastering. The Linux is almost entirely used for software that I’ve made myself. In the past year, I’ve got really into working with audio and neural networks.”

MT: For those that may be unfamiliar, can you go into neural-network technology?

BJ: “Sure. It’s kind of funny, because I thought I was the first person putting audio into this incredible technology and then Google dropped something called Magenta! The easiest way to describe it is machine learning; you can train your computer to use an hour of a recorded voice for a day and have it learn every single thing that’s going on with that recording – and the next day, come back and using programming or code, tell it to be a human voice. It’ll either sound surprisingly accurate, surprisingly shitty or something completely nuts.”

[Modula id=’14’]

MT: Can you apply machine learning to effects processing, too?

BJ: “It basically ‘learns’ from a source file of recorded music and an impulse file, which could be anything from a recorded reverb impulse to a pad or waveform. It then uses GPUs to render a result that is harmonically perfect, which makes normal reverb sound random or messy by comparison.

“It sounds like reverb, but it’s a little better because it’s actually just a spacey tone playing in the background that’s melodically correct and you don’t have any frequencies that aren’t in the original recording. The sound is not being dispersed like it is with reverb, it’s actually using machine learning to figure it out. The first sound you hear on my new album is that effect happening.”

MT: You mentioned Google’s Magenta project. Is that the only pre-existing software that can currently do machine learning?

BJ: “That’s the closest you can get right now. A great neural-network SDK platform is TensorFlow. Have you ever seen those deep-dream images? They were pretty popular on the internet about two years ago. You’d feed an image into the computer and it would dream up a bunch of weird dogs that would appear as though they’re tripping. It’s basically artificial intelligence; you’re training the computer to learn.”

MT: So are you still using plug-ins and VSTs for sound generation these days?

BJ: “Not as much. I still like Reaktor and Pure Data a lot. There’s actually a computer-game company that I’m working with that is using pure data inside the engine for physical modelling and I just went crazy for that. I’ve got pretty proficient in making synths and sounds, especially physically modelling to make an instrument sound like a bell or a vibraphone.”

MT: Have you tested this out on your own music?

BJ: “Absolutely. For example, right towards the end of the track Starlight, you’ll hear a bunch of cellos come in. I just tweaked a certain variable in the physical modelling and it exploded into this crazy sound, then I brought it right back.”

MT: The horns on the closing track Goodbye Bastion surely can’t be software-generated?

BJ: “They’re real horns. I rented a trumpet player for that and a saxophone player for the track Wind. In terms of being a musician, those are probably the hardest moments on the entire album, because they’re not instruments I play that often – because of the lips. I was dizzy from playing the sax all day and my lips were all cut up from using the reed.”

MT: Do you think the gulf is being bridged between virtual instruments and the real thing?

BJ: “It’s interesting you ask that, because it goes long with what I was saying about neural networks. I don’t think we’re there yet, because the machine I use for neural networking has three super-high-powered GPUs and can do an enormous amount of computing for video rendering and data mining.

“Once we get to the point where computers are fast enough to actively do that kind of stuff, you’ll be able to have a VST that, instead of saying we’re going to modulate a violin to sound this way or have this type of vibrato on every note, will be able to study as much violin playing as you can give it, reproduce it and make it almost indistinguishable to the human ear. I think that will probably be the next big step in the whole Kontakt library world.”

MT: You mentioned using the reed on the saxophone, but of course, that would be missing on a virtual instrument?

BJ: “You do have those MIDI wind controllers. I’ve never played with one of those, but MIDI guitar is something that I use live a lot, even though I feel it’s being held hostage by Roland, for some reason. Every 10 years, they’ll release something that’s groundbreaking and then they’ll ignore that entire market for another 10 years.

“The Roland VG-99 is 10 years old and I was hoping I’d hear something new at this year’s NAMM. It basically uses a MIDI pickup as a normal guitar pickup and if I want to retune the strings, then since it has a different pick up for each string, it will automatically tune it however I want on stage. So I can change the tuning with a foot pedal and change it right back, or I could have distortion on one string and another that’s clean. This is really incredible for instrument players, but I feel like there’s probably more money in making pedals.”

MT: Until the demand is there, companies are probably reticent to make the investment…

BJ: “That’s where the industry is. How many VSTs come out that are recreations of analogue synths, or something that already has five recreations? It’s kind of frustrating, but you would imagine people are eventually going to get bored of buying this stuff and want something more inspiring and revolutionary.”

MT: You could relate it to surround sound. There’s so much to explore, but everybody still sits at home in front of stereo speakers…

BJ: “I used to think that surround sound was definitely the future and started learning how to mix that way. This was 12 years ago, but I started noticing that every single house I went to that had a surround-sound setup had all the speakers set up next to the TV [laughs]. People don’t actually give a shit about any of this stuff, so how could we expect to them to actually read a bunch of books on how to set up surround sound properly?

“Even when I master my music, I always cringe, imagining that 30% of people who listen to this album will be listening on laptop speakers from across the room, a Bluetooth speaker or Apple’s default headphones that come with the iPod…”So I can change the tuning with a foot pedal and change it right back, or I could have distortion on one string and another that’s clean. This is really incredible for instrument players, but I feel like there’s probably more money in making pedals.”

MT: Until the demand is there, companies are probably reticent to make the investment…

BJ: “That’s where the industry is. How many VSTs come out that are recreations of analogue synths, or something that already has five recreations? It’s kind of frustrating, but you would imagine people are eventually going to get bored of buying this stuff and want something more inspiring and revolutionary.”

MT: You could relate it to surround sound. There’s so much to explore, but everybody still sits at home in front of stereo speakers…

BJ: “I used to think that surround sound was definitely the future and started learning how to mix that way. This was 12 years ago, but I started noticing that every single house I went to that had a surround-sound setup had all the speakers set up next to the TV [laughs]. People don’t actually give a shit about any of this stuff, so how could we expect to them to actually read a bunch of books on how to set up surround sound properly?

“Even when I master my music, I always cringe, imagining that 30% of people who listen to this album will be listening on laptop speakers from across the room, a Bluetooth speaker or Apple’s default headphones that come with the iPod…”