Contemporary Production: Prosody In Technology

Prosody is a term we use to define the uniting of the sonic and lyrical elements of a track. To demonstrate, Erin Barra deconstructs one of her compositions. Catch up on the previous instalments of Erin’s contemporary production series with expressive instruments in Ableton and MPE controllers. Prosody’ is a word I use a lot. […]

Prosody is a term we use to define the uniting of the sonic and lyrical elements of a track. To demonstrate, Erin Barra deconstructs one of her compositions. Catch up on the previous instalments of Erin’s contemporary production series with expressive instruments in Ableton and MPE controllers.

Prosody’ is a word I use a lot. Its meaning was taught to me roughly 15 years ago by Berklee professor Pat Pattison and in some ways, it’s become the foundation for what I consider to be art – or at least the kind I’m interested in.

In the words of Pat: “Aristotle said that every great work of art contains the same feature – unity. Everything in the work belongs – works to support every other element. Another word for unity is prosody, which means the ‘appropriate relationship between elements, whatever they may be’”.

Some examples of prosody in songs might be: prosody between words and music – a minor key could create a feeling of sadness to support or even create sadness in an idea. Prosody between syllables and notes – an appropriate relationship between stressed syllables and stressed notes – a really big deal in songwriting. When they’re lined up properly, the shape of the melody matches the natural shape of the language.

Prosody between rhythm and meaning – obvious examples like, “you gotta stop! (pause)… Look and listen.” Or writing a song about galloping horses in a triplet feel. The elements all join together to support the central intent, idea and emotion of the work. Everything fits.

Mainstream examples of this include Garth Brooks’ song Friends In Low Places and Michael Jackson’s Man In The Mirror. In Brooks’ song, the melody of the song when he sings: “I’ve got friends in low places” is pitched quite low on the word ‘low’, again, sonically mimicking the intention of the lyric.

Or in the last chorus of Man In The Mirror, there’s a half step modulation up on the word ‘change’, reinforcing that the narrator himself is going to make that change. There’s so many ways prosody manifests itself in music; harmonically, melodically, rhythmically, lyrically… and perhaps the thing that gets talked about the least and what I’d like to focus on here, is sonically.

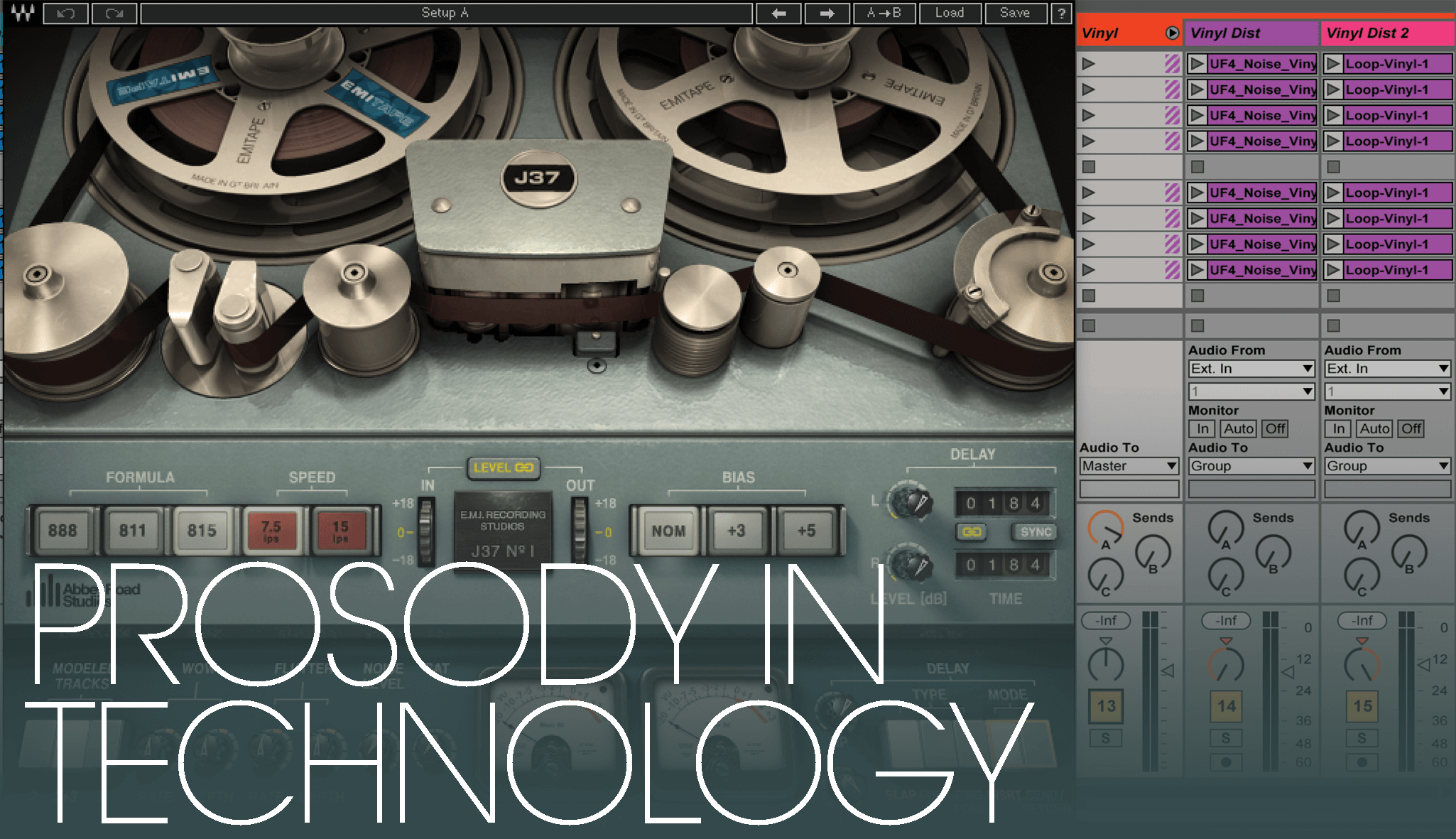

Two vinyl distortion loops, panned left and right, and drenched in reverb and run through the Waves J37 plug-in

About seven years ago, I was working with a mix engineer on a song of mine and I suggested he add a delay throw on the lyric “begin again”, pointing out that the delayed signal was in and of itself beginning again, and wouldn’t that be a cool way to spotlight that lyric?

He looked at me a little confused and asked me which part of the song that was in, which is when I realised that after countless hours into working on this song, he hadn’t been listening to the lyrics at all.

It’s almost too easy for us as producers and engineers to get completely caught up in the way something sounds without stepping back and taking a full view of what it is we’re working on and why it was composed in the first place.

Writers are constantly encouraged to make these deep connections as often as they can, making sure to pick the right musical tool to tell a story – but we hardly ever talk about these artistic choices as engineers and producers.

To Illustrate the power of sonic prosody, I’m going to walk you through a piece I wrote and produced titled House On Fire. You can watch my performance of it and tutorial breakdown via the DVD included with this issue, or by searching for it on YouTube.

I’ll be pointing out the sonic connections that make this piece work as a whole and create an interconnected listening experience, while touching upon some of the compositional elements as well.

Primary inspiration

First off, let me tell you where the song came from. I have a friend that I often find myself writing about. She lives her life with a sort of reckless passion that is almost diametrically opposed to my own life, which simultaneously confuses and inspires me.

A few years ago, she found herself in a broken marriage that she was desperately trying to cling to while singlehandedly ruining it through her own actions. I remember saying to her one day: “It’s like you’re living in a house that’s on fire, but you two are just sitting in the living room pretending nothing’s wrong.”

Once the phrase came out of my mouth, I knew I had stumbled upon something good, and thus House On Fire was born. I wanted to capture the desperation, anger, confusion, blame, sadness, rage… all of it, inside this burning house of a song/production.

Needless to say, I needed to start a fire so I began with some vinyl distortion. I took two separate loops, panned them right and left, drenched them in reverb with a bit of J37 slapback tape delay and next thing you knew, I had a warm crackling fire.

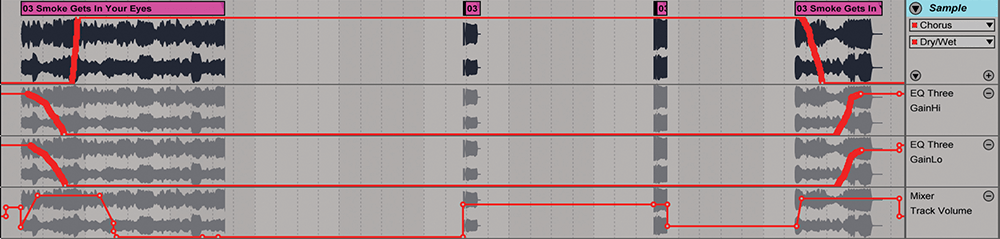

Then I used a sample of Smoke Gets In Your Eyes written by Jerome Kern and Otto Harbach in 1933, and later recorded and made hugely famous by The Platters in 1958. The lyric I was most interested in using was: “They said ‘someday you’ll find all who love are blind’/ When your heart’s on fire, you must realise, smoke gets in your eyes”.

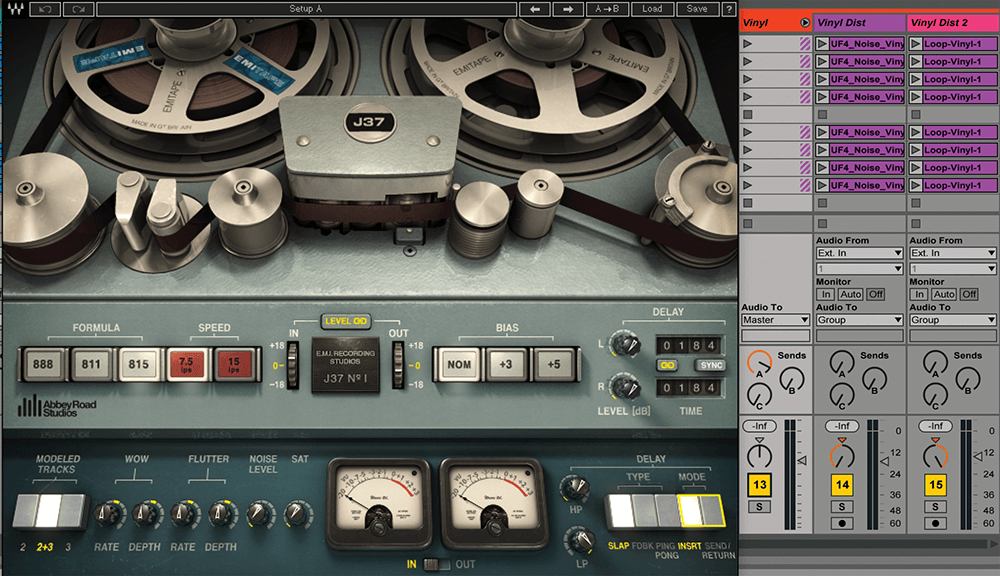

Four automation lanes showing filtering of lows and highs using Ableton’s EQ3 and the Dry/Wet knob on the native Chorus.

Since this is a story about a love which starts off with the best of intentions and slowly deteriorates, I start by just playing the sample as is, and then slowly filter out the low and high frequencies to create a sort of telephone effect which mimics the growing distance between these two people, then add a chorus to smear and diffuse the signal.

I could have gone further by doing some bit reduction, distortion, etc. I also use smaller snippets of this song elsewhere. I took a part where the lead vocalists held an ‘Oh’ and his voice sort of broke in this desperate way, pitched it up and slowed it down, turning it into an unsettling scream I trigger right before the chorus.

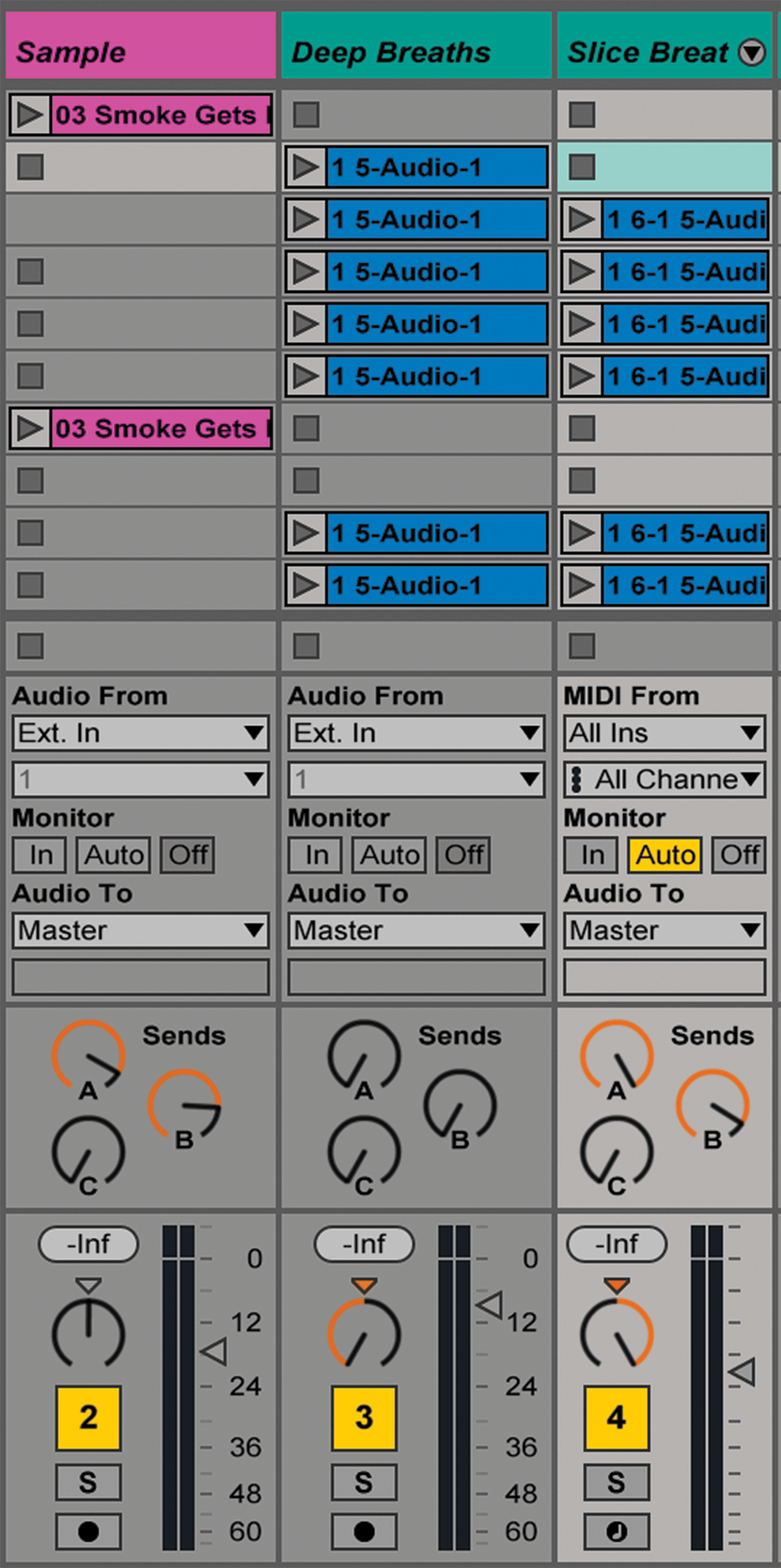

Then I did some deep breathing… literally. I took a variety of deep breaths into an AT4050 running through an Apogee Duet, then took that file and sliced it up on another track in a sampler and grouped the two tracks together.

On the sliced track, I sequenced a new rhythmic pattern of the breaths, which I again drenched in reverb and delay while keeping the original file completely raw and as is, then panned the two left and right. Just the breaths themselves in this iteration, paired with the vinyl distortion, are enough to make you feel like something terrible is about to happen, foreshadowing what’s to come.

Next thing I did was slice up a breakbeat and resequence it so that the rhythm felt both ‘on’ and ‘off’, by switching back and forth from straight subdivisions of the beats to triplets. I was trying to create a sense of rhythmic stability for the piece that simultaneously felt very unstable, again mimicking the relationship in question.

A sample of Smoke Gets in Your Eyes by The Platters, and two tracks of deep breaths, one panned to the left and left completely dry, the other sliced and resequenced, then panned to the right and heavily effected.

From there, I used a digital emulation of a Mellotron choir called Microtron by Puremagnetik to lay down the harmonic foundation. Generally speaking, I find Mellotron choirs to have a really eerie sound, so using it was an easy conclusion to come to.

I used chords that had tense intervals, like 4ths or clusters of three adjacent notes playing simultaneously. To make it even more tense, I used an LFO to modulate the volume, creating a tremolo effect that was running at a frequency that was not synced to any subdivision of the bpm, so it just felt ‘off’.

Borrowed sounds

As you can tell, samples and samplers play a huge part in making this piece a success and are a big part of my compositional process. Between sampling my own audio, using other people’s audio or an instrument such as a Mellotron, there’s a whole lot of sampling going on.

To me, it’s a lot like borrowing a chord progression from another song or building a new piece around a lyric from another – both of which are things I’m not ashamed to do. Similar to sonic prosody, this sonic borrowing is just a further extension of my writing process.

At this point in the piece, I still haven’t sung a single lyric of my own, but the choices I’ve made in terms of my sonic palette, effects processing and automation have done a lot of talking on my behalf. When I perform the song, the arrangement gets built in real time via live looping of MIDI sequences, creating a slow build to the verse.

Usually, I wouldn’t have such a long intro in a song, but in the context of a performance, it made a lot of sense and helped to create that looming sense of impending ‘something’.

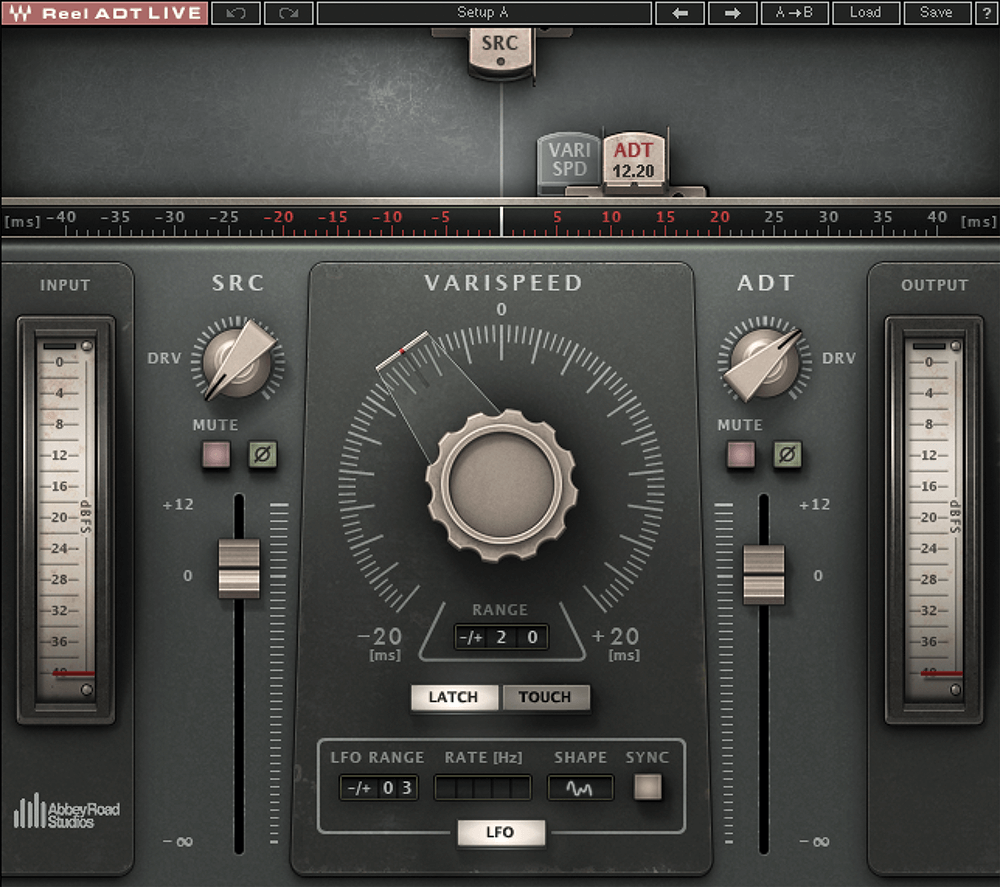

Saturation, drive and tape delay, via the Waves Reel ADT Live plug-in and used as an insert on a vocal chain.

Quarter-note delay via Waves H Delay, used in parallel on Send B.

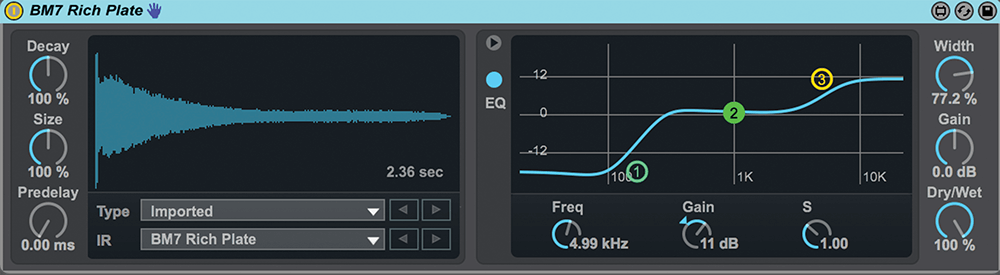

Max For Live Convolution reverb emulating Bricasti’s M7 Rich Plate setting, used in parallel on Send A.

Emotional effects

When it came to the vocal, I knew I wanted to obscure and process the signal in a way I typically wouldn’t. A lot of the time, when I’m creating a vocal chain I’m looking for warmth, clarity and presence, but considering what the song was about, all of those things seemed wrong for this composition.

I settled on bussing way more reverb and delay than is usually considered tasteful, which helped to smear and obfuscate the signal, but the rug that pulls this whole vocal chain together is an Abbey Road Reel ADT, which I used to create an eerie double-tracking effect – which I drove pretty hard.

The end result is catered, custom and to me, adds a huge amount of meaning. Melodically, I’m holding out notes while slowly gliding up or down into other tones, trying to mimic the sound of an alarm or siren. I also end my phrases on unstable tones, so that you never really get a sense of arrival or safety.

The next texture I addressed was the bass, which I synthessed using a Moog Minitaur running through an MF Drive pedal. To me, analogue synthesis offers the ultimate depth and warmth and, when overdriven, it gives me that extra edge of grit and gnarl, which works perfectly for this piece.

Since the song needs room to evolve, I actually hold off on engaging the overdrive until the very last chorus, where the emotional narrative moves from denial and blame to outright rage. I reinforce this harmonically by only playing the tonic pedal throughout the entire piece leading up to this last chorus, which in this instance, happens to be the note D.

The Mellotron is harmonically progressing, but it’s pinned down by this single note which won’t allow it to move. I imagine that’s what being in a failing marriage might feel like; this desire to move ahead while not being able to. In the last chorus, I release that tension and engage the overdrive, allowing the bass to follow a rising-lne cliché shadowing the rage and anger this part of the song represents.

After this emotional peak in the last chorus, there’s an arrangement break where we reach a point of sadness and even perhaps acceptance. The majority of the textures fall away, leaving our protagonist at the end of the song, exhausted and having reached some point of clarity. To underscore this, I rerun the Platters sample, this time reversing the automation, removing the chorus and filtering the lows and highs back in, bringing the signal back into focus.

To conclude, all we’re left with on the song is the crackling fire, this time representing the ashes of what once was a house, and then we fade to black on the master.

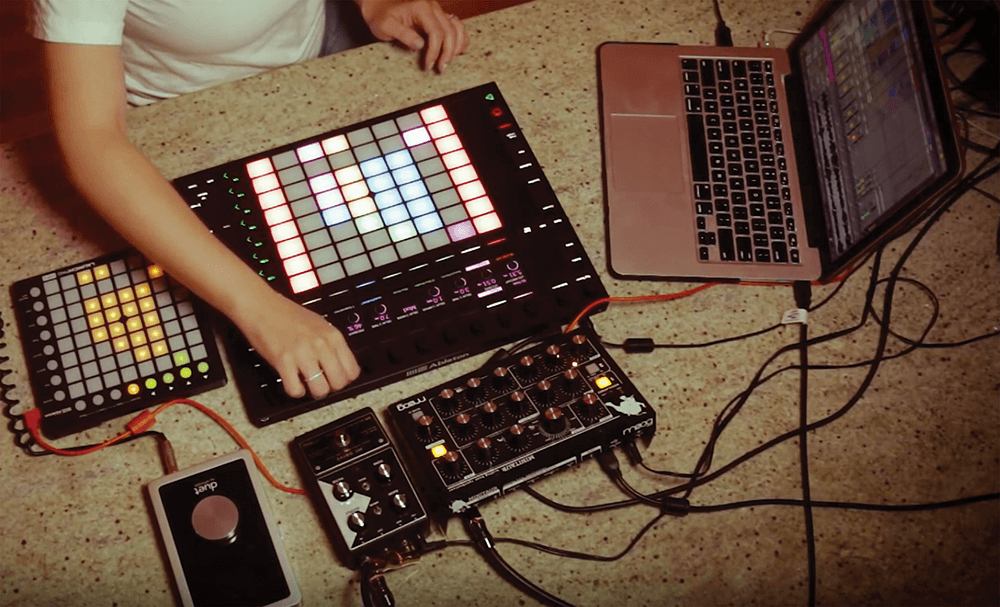

Hardware used in the performance:

Ableton Push 2, Novation Launchpad Mini, Apogee Duet, Moog Minitaur, Moog MF Drive pedal, AT4050 (not pictured), MacBook Pro.

Don’t think…feel

When I perform and listen to this song, I feel feelings, which I believe to be the point of why music gets made in the first place. Creating these deep connections between the stories we tell and the tools we choose to tell them, to me, is art.

Technology doesn’t have to be purely a technical tool, it can be very creative if you approach it in this way. Hence, during this article, I’ve touched on how prosody can manifest itself through automation, sampling, synthesis, effects processors, engineering, sequencing, software and hardware instruments and arrangement, not to mention all the musical interplay.

I happen to be both the composer and producer in this instance, but whatever role you’re playing, you just need to look for and find these type of connections. Next time you’re engineering a song, ask yourself what it’s about and how you can you reinforce those ideas via your mic’ing techniques, signal-flow management or the choices you make in the mix.

On your next production, take a step back and look for ways to link the sonic canvas you’re creating to the emotion the song is trying to communicate. I guarantee that both you and your listener will walk away feeling more connected.