How the computer became the ultimate synth

Virtual synths have become an established part of the music-technology landscape, but that wasn’t always the case. Let’s explore how the computer has basically become the ultimate synth…

Image: Nicky J. Sims / Redferns

It is said that Atari’s decision to include MIDI I/O in the ST computer was something of a last-minute whim of its management and that the company’s engineers weren’t convinced it would bring any benefits. Whether or not that’s true, what’s without doubt is that it was a decision that was to revolutionise music-making.

Before the ST, the recording world was very stratified, with the only route to top-notch results being to fork out for time in a professional studio – this tended to be a very expensive way to work a demo up to a finished piece, though! But the ST, coupled with a new class of MIDI sequencer software from fresh-faced companies such as Steinberg and C-Lab (the original developers of what is now Apple Logic), gave musicians access to a powerful but affordable toolset that delivered professional results while allowing users to tinker with and perfect their creations to their heart’s content.

The ST had a big impact in pro studios, too, taking on all MIDI recording and playback duties while being synchronised to the studio’s multi-track recorder via SMPTE (pronounced “simp-tee”), a timing-signal format developed for use in film and TV production that stands for “Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers” (as Frank Zappa fans will be aware – check out the song Baby Snakes…)

By the early 90s, computers had started taking on audio-recording duties, too – and by the end of the decade, this capability had been expanded to include powerful editing, mixing and effects processing. Key to this expansion was the development of software architectures that allowed additional processing algorithms to be added in the form of so-called ‘plug-in’ software. Incorporating synthesizers into this mix was the next logical step.

Although plug-in instruments are much more resource-hungry than most effects plug-ins, the amount of resources available was increasing exponentially from one generation of computer CPU to the next. Because of this, by the time the second decade of the millennium was getting underway, even an inexpensive mid-range computer was capable of hosting quite a few instruments simultaneously.

An infinite variety

The total abstraction of synth engine from audio hardware, coupled with the vast processing power of modern CPUs, shattered the few remaining barriers to sound-synthesis nirvana: huge amounts of RAM and data storage coupled with super-fast hard disks and data busses allowed sample-based instruments to work with vast, detailed, multi-gigabyte sample libraries.

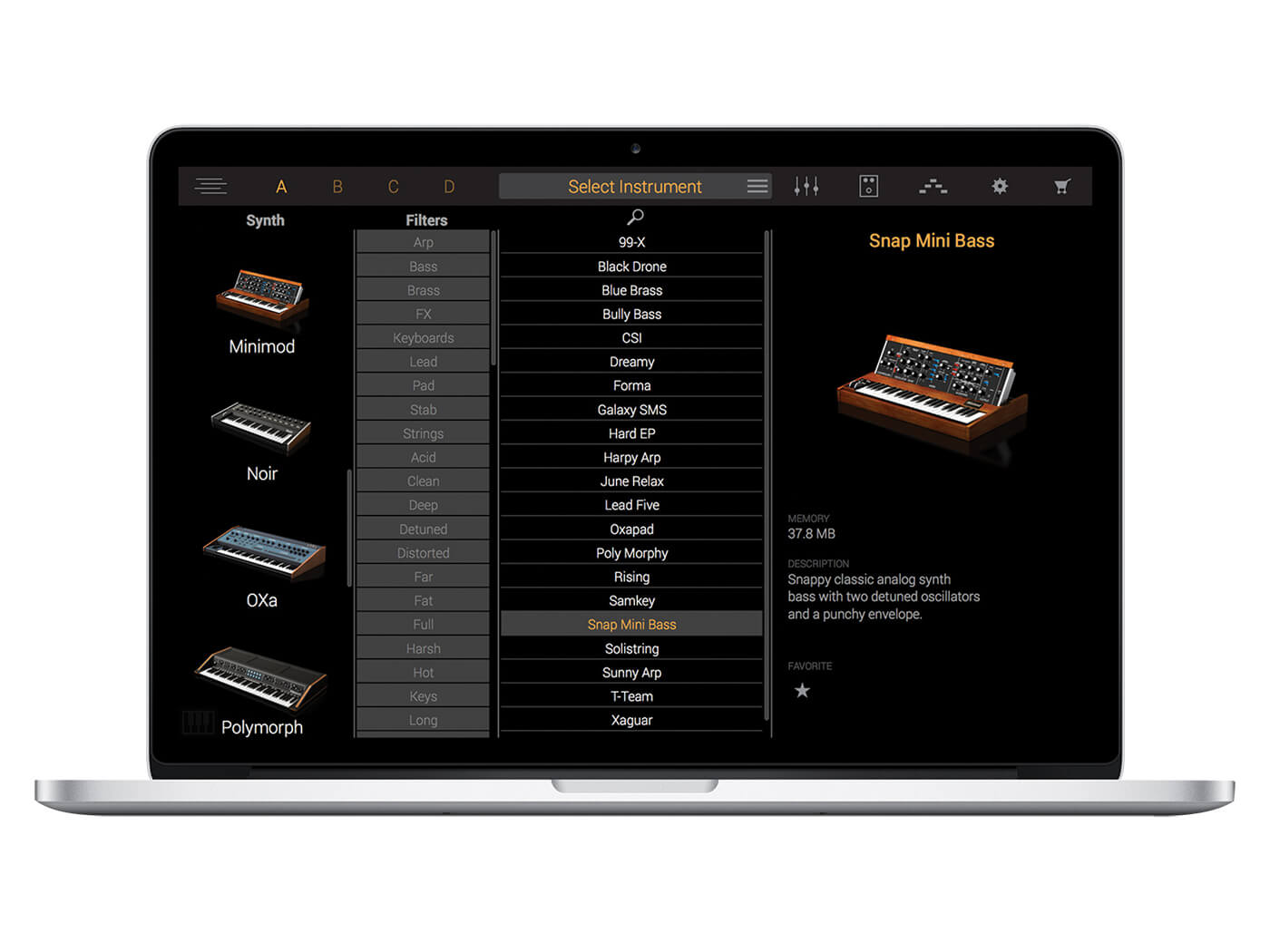

Old digital synthesis techniques that had largely fallen by the wayside were given new life, with the tiny two-line LCD screens of yesteryear replaced by sumptuous high-resolution user interfaces that massively simplified sound editing. And analogue modelling allowed for a near-infinite variety of virtual-analogue subtractive synths, with a growing tendency for these to be modelled on classic analogue instruments from the likes of Moog, Sequential Circuits, PPG and more.

And so it is that finally, after nearly a century of innovation, blind alleys, bankruptcies and successes, sound synthesis reached a point of near perfection – and the humble PC had become the ultimate synthesizer. But technology continues to advance at an ever-increasing rate and so the story of synthesis doesn’t end here.

The next wave of change is already coming into view in the form of software synths that run on hand-held touchscreen devices, the resurrection of classic subtractive synths using analogue components which behave identically to the originals and the re-emergence of very high-end boutique analogue instruments… We’re almost back to where we started!