Tony Visconti Interview – The Superman

Of all the towering figures in music production history, there is no-one quite as innovative (and unpredictable) as Tony Visconti, from his early days working with a young Marc Bolan to the career-defining highs with David Bowie, Visconti has always been keen to push the boundaries of what is possible in the studio. Andy Price […]

Of all the towering figures in music production history, there is no-one quite as innovative (and unpredictable) as Tony Visconti, from his early days working with a young Marc Bolan to the career-defining highs with David Bowie, Visconti has always been keen to push the boundaries of what is possible in the studio. Andy Price sits down for a chat with a bona fide production legend…

Image courtesy Getty Images

Tony Visconti’s name is one of those that is now enshrined in the annals of history. Since the late sixties, he has been involved in music making and production, working with some of the most important artists of their respective generations. T-Rex, Iggy Pop, U2, Morrissey, The Moody Blues… the list of artists whose work Visconti’s production has enriched goes on and on.

Perhaps the work he’ll forever be celebrated the most for, though, is the revered records he’s produced for David Bowie, including his most recent – 2013’s stealth surprise The Next Day. Visconti met Bowie at a young age, working on his Space Oddity LP – he also provided bass for his early band.

As Bowie’s talents and reputation grew, Visconti became one of his closest musical confidants and the producer of the bulk of Bowie’s greatest material, including Young Americans, Scary Monsters and the universally acclaimed Berlin Trilogy.

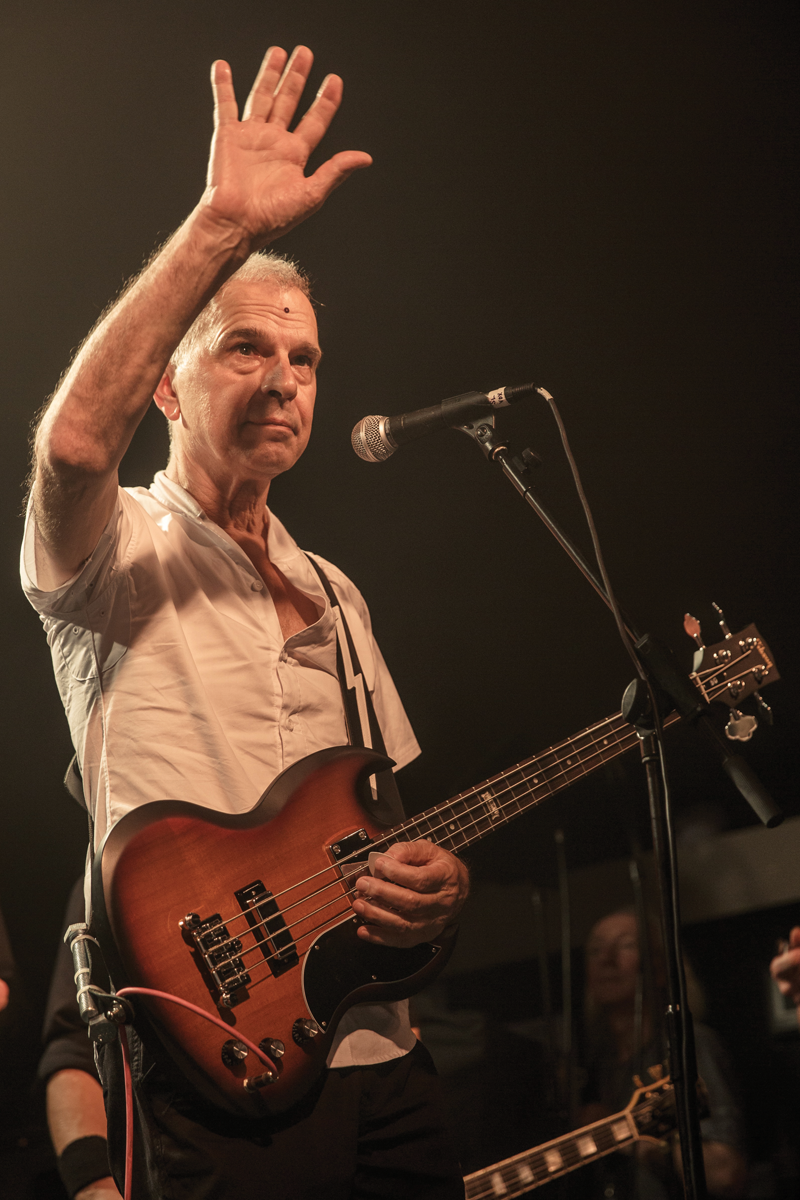

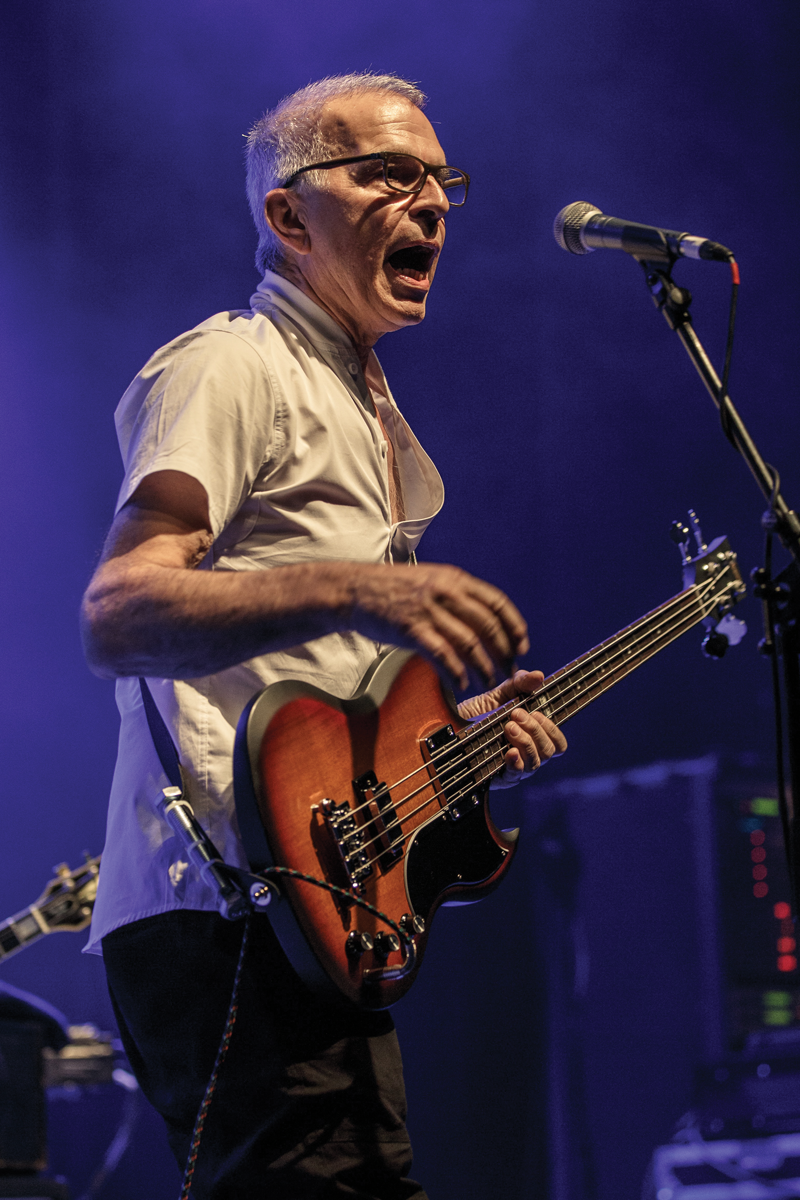

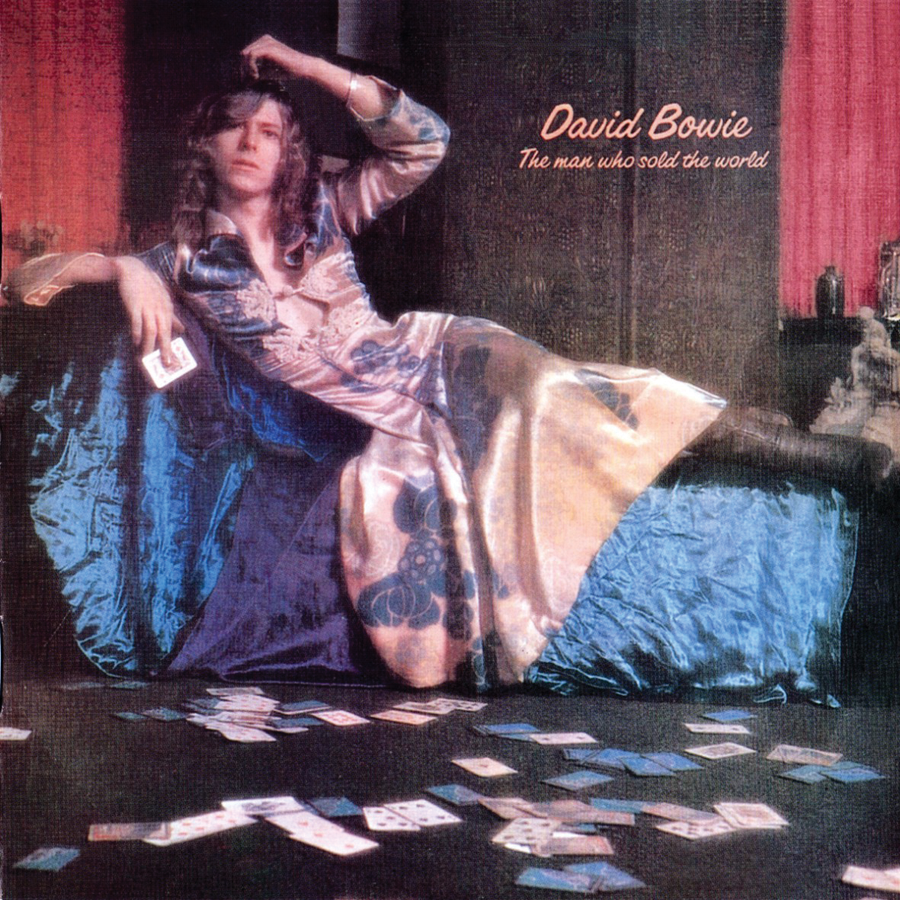

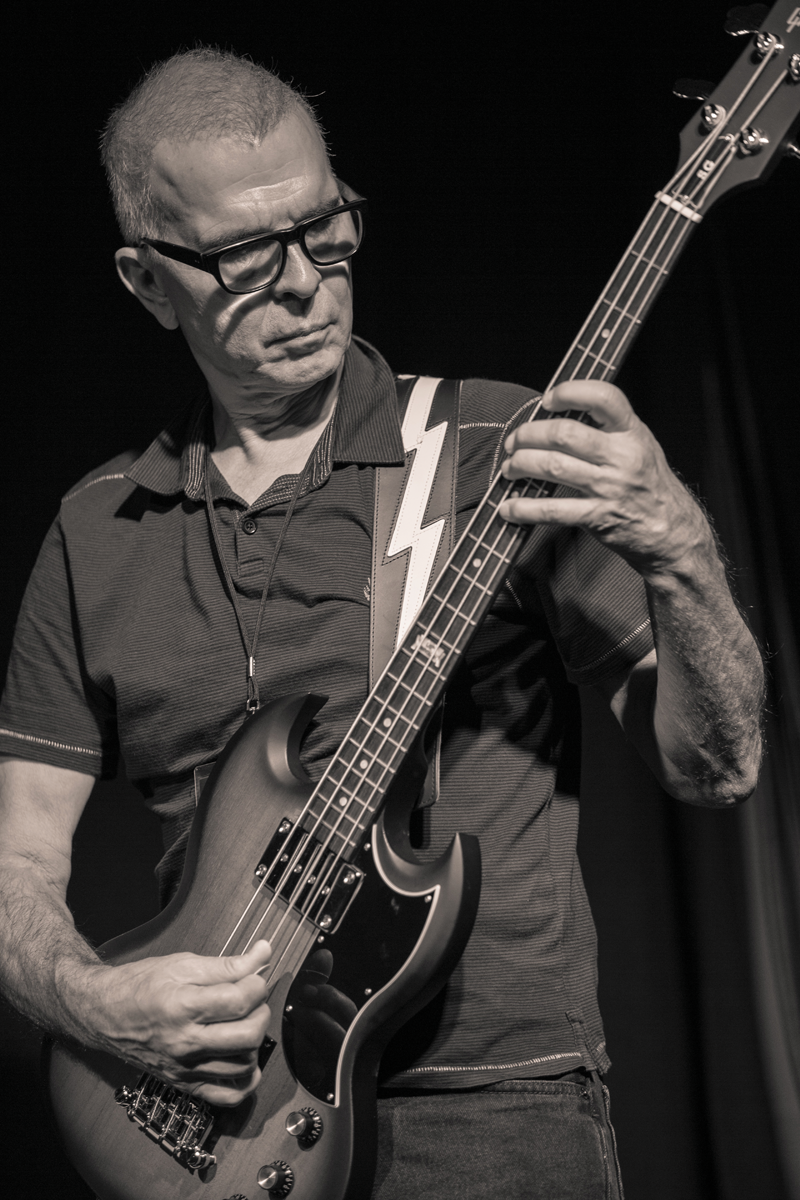

Recently, Visconti has been back out on the road, alongside former Spider From Mars Woody Woodmansey and Heaven 17 vocalist Glenn Gregory in the band Holy Holy, performing the (previously never played live) Bowie album The Man Who Sold The World in its entirety. We spoke to Visconti about his production philosophy, working on some of those legendary records and what it’s like to be back on the road again…

MusicTech: How did you first get into music, and then into record production?

Tony Visconti: I learned to play ukulele when I was five – my family was a musical one. I spent the next 15 or so years doing almost every conceivable gig you could get as a young man in New York City, including recording sessions.

I was totally fascinated by how records were made. When I heard people like Les Paul and Mary Ford, and then The Beatles’ Revolver album, I knew there was an even deeper alchemy involved and I was hooked, I had to learn recording technology.

A chance meeting with producer Denny Cordell by a water cooler in a NY office led him to hiring me for my music abilities for his assistant in London. That happening was like an unbelievable film script. It was in London where I learned my craft.

MT: Do you tend to get involved in the composition process with the artists that you produce?

TV: Of course I get involved in the creative process, I’m a fully qualified musician and arranger. I became a recording engineer and mixer late in the game really.

I almost always use a great engineer for the tracking of a band because I am far more concerned with the performance of the band. I’m in the studio more than I am in the control room.

This is mainly why I’m hired. For vocals, etc, I take charge of the engineering, with an assistant, because of the speed I like to work. The overdubs are a much more creative process and I find some engineers too slow to work with at this stage.

I also mix most of my productions by myself for the same reason. However, a great tracking engineer is invaluable to me.

Tony on the road with Holy Holy (Photo courtesy Chris Youd)

MT: Do you tend to favour analogue gear, or have you adopted digital technology into your setup?

TV: I am a big fan of analogue gear. Drums sound great recorded through a Neve console, but since the 90s we all realised that once you’re finished recording the backing tracks you can finish the project with a handful of great mics and preamps.

You don’t need that drum studio to record vocals and guitar solos, for instance. For reverbs and special effects, however, the digital in-the-box versions are just as good as standalone boxes, and in many instances better.

An H3000 in the box is just wonderful. When the budget permits, I record a band on analogue tape, but overdubs are done in Pro Tools. That’s the way we are now, addicted to the speed and editing possibilities of digital recording.

MT: So what would you say is the cornerstone of your studio today?

TV: I work in Pro Tools mainly, and sometimes in Logic, on a powerful Mac with hundreds of plug-ins, lots of UADs. I used to have a fabulous studio in London, called Good Earth.

The classic 1176 was used on The Man Who Sold The World. Tony’s New York studio today contains a combination of classic preamps and Pro Tools

I had a hot-rodded SSL E series and great outboard gear, but I sold it all to go back to New York in 1989. Today, in my small studio in Manhattan I have a nice collection of analogue preamps and dynamic gear, some with valves, some FET, that give me a wide variety of flavours to put into Pro Tools.

I record drums in larger studios, like The Magic Shop in New York. I can’t do that in my small studio.

All The Madmen

MT: How did the idea to form Holy Holy first get off the ground?

TV: Basically, on a dare from Woody Woodmansey. He pointed out that the David Bowie album The Man Who Sold The World was never performed live. We split up as a band immediately after it was delivered. It happens to be one of my favourite albums that I’ve ever produced, and one that I played kind of insane bass parts on – so I took the challenge.

Holy Holy is Woody’s band, a very versatile bunch of musicians. I accepted the challenge, which led to three months of practice to get back into shape. I always play something on my productions, but playing in the studio is more forgiving than a live performance. I told myself that if I was going to pull this off I’d better be good at it…

A young Visconti along with former Spider From Mars and co-Holy Holy band member Woody Woodmansy during the Man Who Sold The World era (circa 1970)

MT: The Man Who Sold The World is very much considered Bowie’s ‘hard rock’ album, would you agree with that assessment?

TV: That album is a big turning point in Bowie’s career – and Woody’s and mine. It wasn’t the big hit we were expecting but, by jingo, it was quite brilliant.

The songs were masterpieces and we pushed ourselves to our limits. Records aren’t made that way these days, these days of dumbing down. Anyway, there wouldn’t be a Ziggy Stardust if we didn’t make this album. Bowie and I parted after this album, but the matrix was made for Woody and Mick Ronson, who brought in their friend from Hull, Trevor Bolder, to take over my role on the bass.

MT: With David, you produced The Man Who Sold The World and a whole range of classic, and stylistically, varied albums throughout his career. How did the experience of making the early work compare to working with David in his later, more experimental days on the Berlin Trilogy?

TV: Over the years, David and I have developed a vocabulary and a musical frame of reference. We met in 1967 and discovered we had very similar tastes in music, like The Fugs, The Velvet Underground, the Stan Kenton Orchestra, The Beatles, The Kinks and many, many more. The list has grown into modern music as well.

We’re good friends, too, which helps, although I hardly see him unless we’re making a record. Recently, we made a single with the jazz composer, Maria Schneider, called Sue (Or In A Season Of Crime). Since we were all on the same page with Stan Kenton, Gil Evans and Maria herself, who was Gil Evans’ apprentice, we just flew through making that exciting recording.

The Next Day was a commercial and critical success which Tony views as one of the finest albums in the Bowie catalogue

MT: The release of The Next Day surprised (and overjoyed) everyone; how long did the making of the album take? And how do you feel about it now after a couple of years have passed?

TV: The Next Day is an amazing album. We made it over a two-year period, on and off. There was no rush because no one was aware we were making it.

There were others involved, but we all vowed to keep it a secret. It was finished when David said it was finished. I definitely think it’s one of his best.

The Supermen

MT: You’ve had such a varied career, working with T. Rex, David Bowie, The Moody Blues and many others – is there a specific highlight that towers above all the others?

TV: The artists of the seventies were from the golden age. If you were a creative iconoclast, the seventies was the best time to be signed. There was more freedom.

I guess the Berlin Trilogy was my highlight of the seventies. Low, Heroes and Lodger were uncompromising, great moments of innovation. I am pleased that creative artists do still exist today, but these times are bad for music generally – it began just before the turn of the century. Labels started dumbing down and signing mediocre artists who had mass appeal due to their appearance or aesthetic.

The epitome of this was the whole Gaga insanity. I think that some of my favourite modern artists are female; I think Florence [Welch] is wonderful, and I loved Amy Winehouse. I have been working with two other amazing female artists, Kristeen Young and Esperanza Spalding – both virtuosos who write fabulous songs and can play and sing like black belts!

MT: How do you select the artists you work with? Do you listen out for people you’d like to work with, or are you sought out specifically?

TV: I rarely seek out artists, I usually wait to be approached. There is no shortage of work for me, I’m constantly working. I have to stick to my ethics.

I have a cultural responsibility to keep standards high, I know that sounds pompous but I don’t want to contribute to the mindless soft material that clogs the airways and internet. I hold out for great artists, they are out there, and I try to do my bit to get them heard.

MT: Prior to your live work with Holy Holy, how frequently did you get out and play live? And do you think live playing is still important for musicians and producers?

TV: Oh yeah, I have to play live to keep my connection with music and the audience that loves music. I have done many local gigs in New York over the past couple of decades, sometimes getting onstage with some band as a guest bass player.

But I have my own show that I put on occasionally, where I am the band leader and I play the whole time, on bass. I call it The TV Show. I hire a few great local musicians to join me, and I get four great singers (the list always changes) to perform about 20 songs that I’ve produced or arranged. There are probably 1,000 to chose from.

I prefer to mix it up with well known songs like Heroes, and some lesser-known songs like She Was Born To Be My Unicorn by Tyrannosaurus Rex. True fans know all the songs. The last TV Show was in January, and I’d like to do one again later this year. It takes a lot of work and rehearsals to make this happen.

MT: When you think about some of the great records you’ve produced that have been released on a range of different formats, how do you feel about modern distribution methods such as iTunes and Spotify, and do you think something is lost when listening to classic tracks from albums such as Low, for example, in this way?

TV: Hmm, that’s a difficult question. I actually prefer the sound of a well-mastered CD over vinyl because of the increased frequency response and lack of surface noise.

Vinyl is a wonderful medium, it’s just romantic. Now, with the file compression of files these days, we’ve taken a step backwards. A well-recorded chrome cassette sounds better than a compressed digital format. But I see Spotify as a kind of advert to invite the listener to buy a high-quality version of the music they like.

It’s not too different from what radio use to be in the seventies through to the nineties. There was always a lot of music you liked but you didn’t buy.

iTunes has made great strides with its Apple Lossless format. I was really surprised when it streamed The Next Day live for the day of its release. Sony brought the head of iTunes to my studio to explain the ‘mastered for iTunes’ technology and

I followed the rules, I bought the plug-in to follow the guidelines. It paid off. The Next Day sounds great on iTunes, and if you still want better quality you can always find it in other formats, including a three-disc vinyl. Back to Spotify, I can’t wait until it is forced to pay a royalty that reflects a record deal royalty.

Otherwise, it will surely bring on the death of a creative profession. I guess when there is a film equivalent, the courts will start to

get it right.

The Man Who Sold The Gear

So what does Visconti remember about the recording process of the album he produced (and played bass on) 45 years later? “Man Who Sold The World was recorded in Advision and Trident studios in London, now defunct, of course,”

Tony remembers. “We didn’t have lot of gear in those days. Standalone preamps were unheard of. They were class-A recording studios, both Trident and Advision made their own consoles, like a few other studios did at the time. Pye and Phillips did the same.

“This is why recordings sound so unique from those times. You can even hear the difference on TMWSTW. She Shook Me Cold is the big Advision sound.

The darker The Supermen was the tighter Trident sound. Both studios, however, did not have lots of outboard gear. For instance, Trident had one LA 1176 mounted in the wall.

You had to make a big decision what you were going to use it for. I worked with great engineers at the time, like Ken Scott, Malcolm Toft, Eddy Offord and Martin Rushent.

“There were no outboard preamps, but the preamps on the console were really great-sounding, and those engineers were masters of British EQ, laying it on during the tracking sessions, something American engineers didn’t do at the time. They preferred recording flat and EQ’ing in the mix only. But this is why I wanted to live in London, to learn the British techniques of making records. They sounded so much better than American records in that period.”

Oh By Jingo!

Photo courtesy Chris Youd

MT: As a seasoned veteran, what tips would you give to young producers who are starting out in their careers?

TV: Follow your instincts and do what’s right for the culture. A record isn’t just cool sounds. Great records are made by gifted artists with something to say and a talent to say it. I’m sure you’ve heard the expression to ‘polish a turd’.

Well, don’t do that! Only work with the best. You don’t have to be famous to find great artists, undiscovered ones are living all around you. If you follow your heart, the hits will come.

MT: Aside from your work with Holy Holy, what’s next on the agenda for you?

TV: There is a little bit more studio work coming up (wink wink) but, honestly, I could use a break! I haven’t had a proper two-week holiday in probably eight years, although it’s nice to make an album in places like Woodstock, Paris and Rome, I’m working six days a week in those beautiful locales.