Blinded Me With Sound – Thomas Dolby Interview

With a new book documenting his incredible life, Thomas Dolby has added ‘author’ to his CV alongside ‘hitmaker’, ‘producer’, ‘keys player to the stars’, ‘Silicon Valley entrepreneur’ and ‘Professor’ (both real and imaginary). Andy Jones meets Dolby to talk tech, and about his studio which is, where else, based on a lifeboat… Thomas Dolby’s book […]

With a new book documenting his incredible life, Thomas Dolby has added ‘author’ to his CV alongside ‘hitmaker’, ‘producer’, ‘keys player to the stars’, ‘Silicon Valley entrepreneur’ and ‘Professor’ (both real and imaginary). Andy Jones meets Dolby to talk tech, and about his studio which is, where else, based on a lifeboat…

Thomas Dolby’s book The Speed Of Sound: Breaking The Barriers Between Music And Technology (to give it its full title) documents his life from starting out in music through to his current role of Homewood Professor Of The Arts at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore in the US. What happens between is an astonishing rollercoaster of several lifetimes’ worth of adventure.

Many, for example, would have been happy enough with just releasing some critically acclaimed albums and scoring a smattering of massive pop hits (She Blinded Me With Science and Hyperactive), but not Dolby.

He went on to found his own Silicon Valley enterprise, supplied a large percentage of the world’s mobile phones with a synthesiser that could play polyphonic ringtones, became the Musical Director for the influential TED conferences and married a Hollywood actress.

And let’s not forget, he played keyboards for Bowie at Live Aid; produced several acts, including Prefab Sprout; had several run-ins with Michael Jackson and even played with Stevie Wonder, Herbie Hancock and Howard Jones at the Grammy Awards. After we suggest it’s like the music-production life of Forrest Gump, Dolby laughs and admits it can read a little like that.

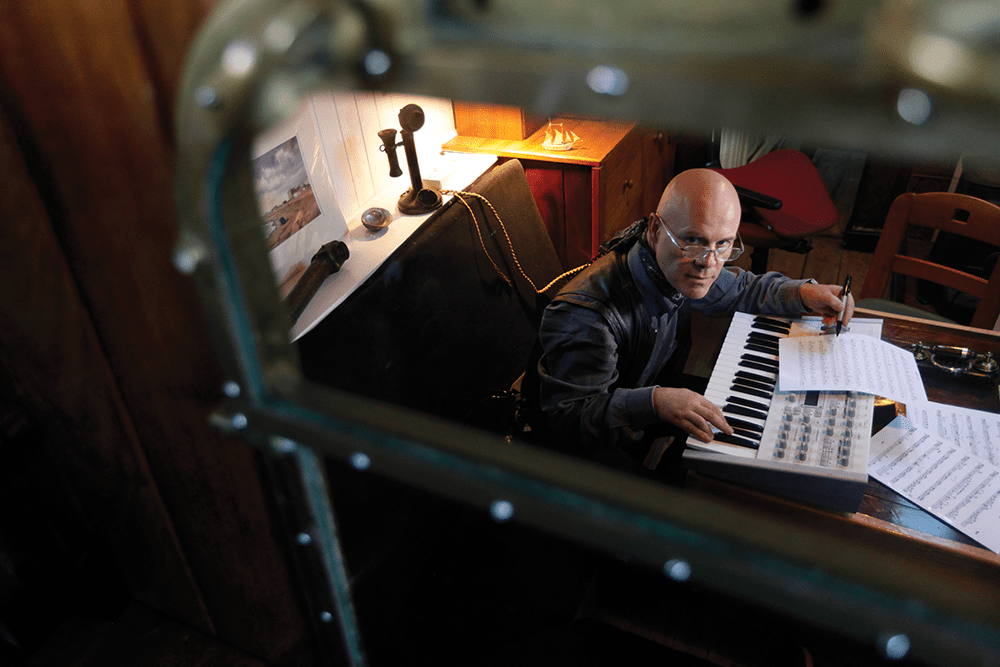

However, we’ve got the rather more serious business of studios to talk to Dolby about today, but of course, knowing Dolby, it’s not quite that straightforward. His studio is based in a 1930s lifeboat called the Nutmeg Of Consolation, which sits in his back garden with glorious views of the East Anglian coastline.

It’s solar- and wind-powered – apt, as it’s the name of one of Dolby’s early hits – and it’s as streamlined as you like, a far cry from his early studio setups that were crammed full of analogue synths and an ultra-expensive Fairlight. Indeed, that move of technology, also a theme running through Dolby’s book in more than one sense, seems an appropriate way for us to

begin our chat…

MusicTech: We’ve witnessed a huge shift in music-production technology since you started in the early 80s. Are you surprised about just how quickly things have moved?

Thomas Dolby: “In hindsight, it’s not that surprising that it has progressed as it has, but I would also argue that the most exciting time for technology was actually in the 60s. Anything musicians would play in a room back then could be recorded and put out as a record. Then, somewhere along the way, perhaps starting with Pet Sounds and Sgt Pepper’s…, recording technology got used for something other than linear recording and became a creative medium of its own.

“You could do stuff in the studio which you couldn’t do live and I think that’s one of the reasons The Beatles stopped playing live, because of the big gap. Then when it came to The Dark Side Of The Moon, technology had advanced so that Pink Floyd could play Wembley and actually do a fairly faithful reproduction of their album.

“Also in that period, when four or five people went into the control room and got really creative with the equipment, it really was possible for something to emerge that was greater than the sum of the parts and there was a sense of occasion about it.

It was new or rare enough that any new idea or combination of ideas resulted in a new sound. There was a limited period when this happened, because, as technology became more ubiquitous and accessible to anyone with the motivation to mess about with it, there was a bigger chance that someone in the world would come up with the same combination. So, in terms of most exciting eras, my career did cover a lot, but I’d also have to take my hats off to the pioneers that came 10 or 15 years before me.”

MT: Do you think those early constraints in the studio and with technology were a good thing?

TD: “It’s a mixed blessing. Very, very few of us had access to those tools, the magic potion, in those days. There weren’t many Pink Floyds and Beach Boys that had time to spend in a luxury studio to mess around. They were the elite, even among the bands signed to record deals and given enough leeway. So it’s a good thing now that anyone who feels inspired can get their hands on technology that’s capable of making music and distributing it, but the downside is that if you take away all the constraints, you take away the need to cut corners creatively and get around stumbling blocks in creative ways.”

MT: Tell us what kind of gear is in the Thomas Dolby studio these days?

TD: “I have very, very little gear. I’m not in the camp that gets nostalgic about old analogue equipment. To me, it’s actually more about the environment that I work in. A lot of the work I do is in my imagination, so for example, my lifeboat studio in East Anglia where I am sitting right now has really very little gear in it, but it’s the state of mind when I’m here. There’s no time limit on it; I could do it for half an hour or 20 hours – or actually, as long as there’s wind or sun, as that’s how it’s powered! People come here and say: ‘How do you get any work done, because we’d just sit and stare and look at the sea?’ And I say: ‘Well, that is me working!”

MT: Tell us more about your studio boat, the Nutmeg Of Consolation…

TD: “It was originally an open rescue boat for a merchant ship, but there’s a wheel house that was added on. I had some local traditional boatbuilders build me the wheelhouse out of reclaimed timber, which is where the control room is, and the rest of it is like a spare room for guests and a workshop/storage room for bits and bobs.”

MT: So what gear do you have ‘on board’?

TD: “These days, it’s a laptop. I have a tower computer that hasn’t been fired up in a while, as there isn’t much I can’t do on the laptop. It’s a notepad for everything I do. There’s a Nord and a Virus, a Moog Voyager, which was a present from Moog, a Lifetime Achievement Award… Then I’ve got a couple of mic pres, and that’s it.”

Making it in music in 2017

Thomas was lucky in that he scored his hits at a time when people made money from doing so – and admits it’s tougher to make it as a musician these days…

“Well, it’s very hard,” he says. “Someone said to me the other day that the charts these days are really how far up or down you come on a festival poster. Everything is about that, as it is one of the only metrics in terms of making a living. Making records is not going to make you a living. Even if you get a deal with a label, it’s not going to get you a big advance to live on. You’ll get a more even split, but you’ll not have the luxury that some of us had when you sign a deal and you can live for a couple of years.

“So it’s not enough to just be great at your instrument and your songwriting any more. You also have to be a marketeer and a business person, a publicist and so on. You are not going to be in a position where someone is going to put that team together and fund it, so it’s either not done, or you do it yourself and beg, borrow or steal to do it.

“The upside of the technology is that the barrier has gone – so tens of thousands of people can do it, but now you’re competing with those tens of thousands of people. There are no filters any more, so to rise above the noise you have to go that extra mile, as it’s not about the quality of the music any more, unfortunately.”

MT: It sounds like a far cry from your earlier studio setups, but is there anything you miss about them?

TD: “It probably comes back to this sense of occasion on it. Very often, when I was working on a song I’d set it all up, work on it for a bit, get too excited, realise I had to get some sleep, go to sleep and there was always that thrill when you woke up in the morning and you had fresh ears and hit play and you were a step more removed than you were at 3am. Things would pop out at you that you couldn’t hear at the time, when you couldn’t see the wood for the trees and your first reaction was a really precious thing, as you were almost listening to it like a stranger.

“So you’d take on board what your gut reaction was and you’d spend the next few hours implementing changes, because you had the confidence that your objectivity was helping you make those decisions.

“And that’s versus today, when I can hit Save and Quit and do something completely different, like go and edit my film or work on my book and it might be two weeks before I open that song again. I’m not saying you don’t have the objectivity now, but you don’t get the freshness, the ‘live-ness’ of when you hoped it was still there in the morning.”

MT: What is the best piece of music-production gear that you’ve used over the years?

TD: “I think probably the Fairlight was my favourite – it was the biggest breakthrough for me. Analogue sequencing in those days was still fairly primitive, so making the leap to be able to cut-and-paste bars and repeat-paste bars was great, and instead of working with individual notes, each of which is generated on the fly, you were working with building blocks – which might be a chord or fully formed vocal line, so suddenly, the harmonic complexity, even though it was only eight voices and a limited memory, was suddenly on a new level.”

MT: It was an expensive piece of kit, though…

TD: “It was insane. The year I bought my first Fairlight in London, the price was the equivalent of four London flats, and the power of that Fairlight you’d probably get in an app now for 99p!”

MT: What sequencer do you use?

TD: “I use Logic, but I use it in ways that it is not particularly suited for when playing live too, so I probably would be better off with Ableton Live for that. When I first saw Ableton, I didn’t seem to relate to it as it seemed to be geared for the kind of constructivist music, what I call ‘symmetrical music’. Some of my music is more like that, but often, it’s more free-flowing than that, so it didn’t click with me. I knew Logic, and it has some powerful tools buried in its innards that I was able to adapt for my purposes. I’d also used a lot of Logic’s own synths, so it would have taken a lot to switch.

“Logic has also become a lot more stable over the years, so I can now run things on a solid-state laptop live, rather than a tower computer. There was a period when there would be a crash every third or fourth show on a tour, where I’d have a crash in the middle of a song. I had a box of old merchandise T-shirts wrapped up in rubber bands that I’d throw out like it was a football game. It makes an event of it and people would read about it, so if I had a crash, a huge cheer would go up!”

Thomas Dolby: the producer

Thomas produced several bands in the late 80s and early 90s, but is perhaps best known for a trio of albums he worked on with Prefab Sprout called Steve McQueen, From Langley Park To Memphis and Jordan: The Comeback. So what does he think makes a good producer in the studio?

“Of course, there are different kinds of producers,” he replies. “There are engineer producers and there are musician producers. A musician producer would be a Quincy Jones or a George Martin and an engineer producer would be a Mutt Lange or a Steve Lillywhite, and different artists need different types of help. Prefab Sprout were open-minded enough to let me shape their arrangements and once the arrangements and the structures of the songs were right, which we did in rehearsal, the recording part was made a lot easier.

“A lot of good productions are built on the foundation of a good arrangement where the parts are good and don’t step on each other and there is space for the vocal to fall in to. It’s where the aural focus of the listener is directed to a solo instrument, to a percussive part or vocal, so the listener is led through – the point of view of the listener is well managed by the arrangement and the production. If you get that right, it’s easy for people to fall in love with the sounds: they shine because of the context.”

MT: What would you like in your studio that perhaps hasn’t been invented yet?

TD: “Maybe some gestural stuff. I’m quite lucky that I can juggle left-brain and right-brain activities, so I can divide 13 by seven while remembering the chord sequence or the melody I’ve just thought of. So I’m quite lucky from that point of view, but I’m not always comfortable. I wish in a way that those gloves, batons or swirly gestural things had taken root a bit, because the tools we have to work with now are a combination of what we had 30 years ago. It’s like the QWERTY keyboard that has been inherited. I’m not really up on alternative interfaces, but am starting a new degree about all of that called Music For New Media at Johns Hopkins about using everything from alternative controllers to EEG brainwaves and things. It will launch in Autumn 2018, so people will come in who are interested in virtual or augmented reality and sound.”

The importance of online…

MT: The internet has become an incredibly important element for you now, hasn’t it?

TD: “Yes it has, and is for all artists. I was listening to a young songwriter on the radio and she was talking about how she put together a South American tour. A handful of fans down there really wanted her to go so she said: ‘Well, if I can sleep on your couch and you can help me set up the gigs, then I will get on a plane and make it work.’

“In a way, that’s a lot more like the musicians of hundreds of years ago who were travelling minstrels benefitting from the hospitality of their patrons. The 20th century was when recording and broadcast gave one person the ability to reach millions of listeners and get paid for it. It went from one musician to many listeners and now there are many more people involved in making music and making something out of it for their trouble.”

MT: And also, the barriers between the superstar pop star and the fan have been removed, which is a good thing…

TD: “I think it is a good thing. When I started, the metrics were radio playlists, sales figures, royalty statements, and chart positions. The audience were just units which added up to ‘x’ number of sales, but they were faceless people and we – as the artist – had very little opportunity to understand why they liked it, how they heard about it and what they liked about it.

“If you played live, you were more face-to-face with the audience and you might hang out at the stage door and sign a few autographs and have a bit of a chat, but it was really very limiting. Today, it’s all about knowing exactly why your audience likes you, how did they find out about it, what was it they loved about the last record, and zeroing in on your sound and fanbase… and that is a much healthier thing, in some ways.”

Getting bands to do it themselves

Thomas used the internet to cleverly distribute his own music via the game the Floating City, but even back in the 90s, he was trying to tell bands that the then-advancing march of the internet and music technology would change the way they operate…

“When it came to the 90s, the internet was growing and the big-label system starting to break down,” Thomas recalls. “And the Sprouts were having some issues with their label, so I said to Paddy [McAloon, the band’s lead singer]: ‘You really should just put out your home demos.’ His studio was getting more sophisticated at home, so the demos were getting better, as he was doing more on his own. And then his brother Martin was teaching music tech at Newcastle and teaching people how to build websites, and their fanbase was emerging online the same way that mine was.

“So I said: “Your demos are wonderful, you could put out a couple of albums a year and not be dependent on major-label funding, Martin could go out and distribute them, get your arms around your fanbase and make sure you have something to offer them, you could make a decent living from it.” But he wouldn’t be swayed, which is a real shame. He has stuff in his archives which is excellent and will never see the light of day.”

MT: And it all came together for you in the A Map Of The Floating City video game…

TD: “When I came back and started making music again in the middle of the 90s, I built my lifeboat and I was sat here writing songs, thinking ‘I’ve nearly got enough for an album’, but then realised that was the last thing people wanted, another CD album. That’s not what is happening these days.

“They’re on social media or playing video games. So I thought the right way to view my music was as a video game or social-media experience, which has the advantage of opening up to a new generation of fans. The idea of the game was that you had to collaborate. You couldn’t be successful without being good at the game, or knowing a lot about the music or the lyrics.”

MT: So, to our final question – over the course of your amazing career, you’ve made albums, had hits, developed a game, had a lot of success with technology, become a lecturer… what would you like to be remembered for?

TD: “For bringing some kind of warmth or humanity to electronic music. One of the things that people love about electronic music is that the machines have a mind of their own. You can applaud them for that quirkiness and make interesting music that allows machines to be machines.

“I think that is what I chose to do with them, and it was quite different. I think it’s unlikely that I will go back to music full-time, as I will always be attracted to something newer and more challenging, but I don’t feel I’m done.”