The E-mu SP-1200: How one sampler ushered in a revolution

Easy Mo Bee, Nick Hook, Cookin Soul and designer Dave Rossum himself guide us through the story of the sampler that changed everything.

If the name Dave Rossum isn’t familiar to you, don’t punish yourself. But it belongs on the honour roll of music production’s prime movers, next to the likes of Robert Moog, Tom Oberheim, Roger Linn, Don Buchla and even Leon Theremin. Rossum may have invented the polyphonic keyboard but, for a litany of lauded producers and artists, his greatest gift to music is the E-mu SP-1200 sampler.

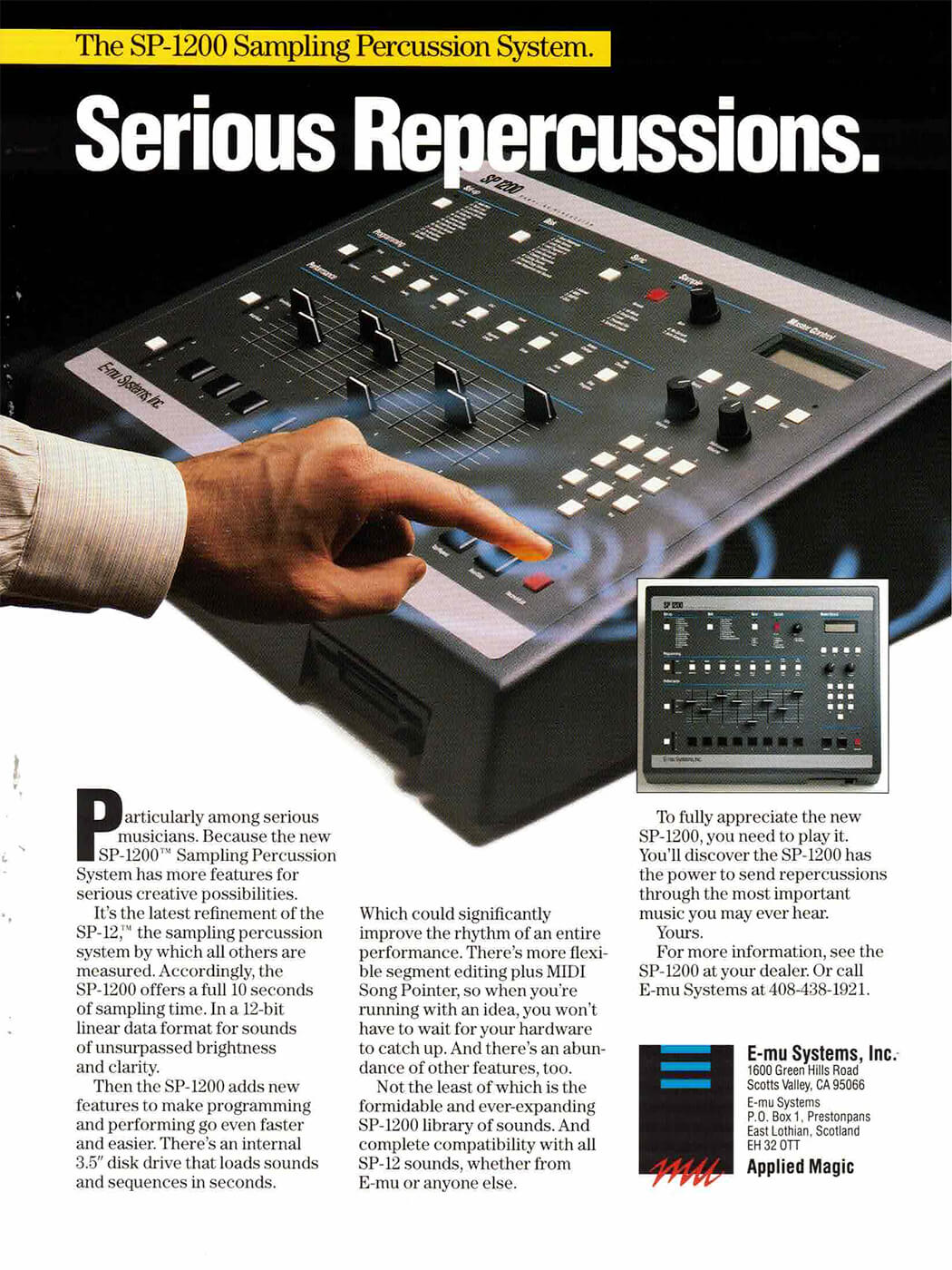

With its eight buttons and respective sliders, miniature LCD screen and numerical keypad, the SP-1200 resembled something between a miniature console and a giant, souped-up calculator. By today’s standards it’s built like a tank and functionally limited. But upon its release in 1987, it was compact, sleek and nothing short of revolutionary. Its loyalists ranged from The Prodigy to Cypress Hill, Daft Punk to DJ Premier.

The SP-1200 helped shape the art of sampling as we know it. Yet it remains an enigma to many contemporary producers. Unlike Akai’s MPC and Roland’s SP series, there have been no variations or updated models. It has ceded recognisability over the years and largely been consigned to the archives of music production history. Why? Mainly because, after leaving an indelible mark on music throughout the 1980s, E-mu Systems would shift focus not long after being acquired by Creative Labs in 1993. While RA Moog Inc was carried through the 1970s thanks to a fluke – the Minimoog Model D – E-mu saw no such luck a few decades later.

However, in late 2021, 36 years after the launch of the original, the SP-1200 received a near circuit-for-circuit, “better-than-new” reissue. At least, circuit-for-circuit in all the ways that matter. The reissue also welcomes a few mod-cons, such as an SD card slot in place of the original’s floppy disc drive.

The major aesthetic difference between the SP-1200 of 1987 and that of 2022 is the name on the back. The original’s ‘E-mu Systems’ logomark has been replaced with 2022’s succinct ‘Rossum’. With the help of erstwhile E-mu colleague Marco Alpert, Rossum Electro-Music LLC was born in 2015 and – alongside returning to E-mu’s foundational craft of modular synthesizers – wasted no time acquiring the trademarks of the SP-1200 and its predecessor, the SP-12.

The dawn of a new era

Rossum speaks to us from his Santa Cruz workshop, all the evidence of a man with no intention of slowing down scattered around him. The 73-year-old recalls E-mu’s breakthrough with the nascent Emulator keyboard sampler in 1980 as a genesis moment. “When we got the sampling feature useable on the Emulator,” he says, “my girlfriend at the time, now my wife, came in and spoke the first words, ‘Mary had a little lamb’, into the sampler, and then we looped it to go ‘Mary had a little-little-little-little-little lamb’.

“I remember that day. A friend of ours named Ken Provost, who played violin, came over and, for the first time, we sampled a violin and looped it so you could play it on the keyboard. Marco was there, also Ed Rudnick [E-mu’s first employee] and probably Scott [Wedge, E-mu president]. They were all very excited, saying, ‘We’ve really got something here! Sampling is cool!’

“We didn’t know it at the time but it really did change how music is made. It was revolutionary. That was our first inkling that sampling was something that musicians could use – and use extensively, that there was a lot more to it than just a gimmick.”

Stevie Wonder bought Emulator #0001, hugging it at The NAMM Show 1981. So exciting was the instrument’s scope that even its factory sounds were used in seminal works.

“Bladerunner,” Rossum recalls with a grin. “There’s a scene where Harrison Ford walks into a bar and there’s this kind of weird, reggae-type beat in the background. That was one of the factory discs in the original Emulator 1, used for testing the looping function. Kevin Monahan, our sound guy, recorded that off the AM radio in Santa Cruz.”

Over the next five years, E-mu would release the Drumulator sample-based drum machine, Emulator II, Emulator III, Emax and the 12-bit SP-12 sampler. “I started making integrated circuits,” says Rossum. “And that was what made us capable of making things much more compact.”

With a total sampling time of more than 10 seconds and floppy disc-based RAM rather than ROM-based memory, the SP-1200 soon superseded the SP-12. “We somehow hit a sweet spot with the ’12 and the ’1200,” Rossum says, “in terms of what the market demanded.”

It was one thing to develop the technology but, during this period, the team’s notion of what sampling actually was saw an evolution of its own. Rossum recalls a conversation with Leon Russell: “He said, ‘You know, when I’m composing with a Fender Rhodes, I know what it’s going to sound like. I know where to put it in the composition. With a synthesizer, I don’t know what it’s going to sound like. It’s much harder to compose with a synthesizer than with traditional instruments.’ And that was a really interesting and eye-opening observation for us.

“That is really what took off with the hip-hop revolution. That combination of urban sounds, the record scratches, the limited fidelity, the gruzzy drop-sample sound, the pitch shifting and the marginal 12-bit fidelity. That all fit so well with that genre, with the emotion it was trying to express.”

A hip-hop revolution

In 1980s America, if any genre was simultaneously expressing the raw spirit of Delta blues and the zeal of 1960s protest music, it was hip-hop. The art of sampling was adopted instinctively by the genre, welcomed by its producers as a natural counterpart to the lyrical compositions of rappers.

This development was not lost on Rossum and E-mu president Scott Wedge, who sought to enable the fast-growing genre to not just continue but proliferate. The SP-1200 proved frustratingly slow in its sales yet stubbornly constant, and with the ever-looming threat of surplus parts, the team at E-mu routinely debated discontinuing it.

“Scott and I had our formative years in the 1960s,” Rossum tells us. “At that time, music was about political and social issues, about change. Things moved away from that in the 70s and 80s. So when hip-hop came around, it was much more toward the music Scott and I loved in the 60s. Scott became a huge proponent of hip-hop. He was the one saying, ‘Let’s keep the SP-1200 in production’. That very nature of the music resonated with us.”

One beneficiary of this decision was a young New York-based producer named Easy Mo Bee, who would later create records with many of the most iconic names in hip-hop and beyond, including 2Pac, the Notorious BIG, Busta Rhymes, Wu-Tang Clan, LL Cool J, Queen Latifah and even Miles Davis.

“I’d say it was around 1986 when sampling became fully-fledged,” Mo Bee tells MusicTech. “When E-mu came out with the SP-1200, [sampling] became more affordable. I still couldn’t afford one though. But I kept hearing this sound – The Juice Crew, or Boogie Down Productions featuring KRS-One – tracks like [1987’s] South Bronx and The Bridge Is Over.

“I finally figured out what producers like Marley Marl, Ced-Gee and Paul C were using: it was the SP-1200. Paul C was an amazing producer whose life ended early. He was murdered. But he was a very important, pioneering producer who used the SP-1200.”

A generation later, Paul C’s own SP-1200 unit would fall into the custody of another young New York producer, Nick Hook. “One of my homies was selling a bunch of gear and had an SP-1200 in the list,” Hook tells us. “I thought ‘Yo, I need that!’ And then I came to find out that it was owned by Paul C. In a lot of ways, I’m holding one of the most important relics in sampling.”

Hook has made records with leading lights of modern hip-hop, from Run The Jewels to Azealia Banks. “The colour, the buttons, the filters, the outputs, the way you do the levels,”, he says, “it’s just a unique sampler. That’s why I feel like any time you hear a song with the SP-1200, you know it right away – the punch of it.”

“It became a personal goal for me to buy this machine,” continues Easy Mo Bee. “Most of the stuff I was doing at that time I was achieving through tape edits. A homemade overdubbing process. But the SP-1200 was going to eliminate all of that.”

The opportunity finally came when Mo Bee’s friend and fellow Rappin’ Is Fundamental member AB Money alerted the artist Big Daddy Kane to what the young producer was doing. “That got me two tracks on the It’s A Big Daddy Thing album,” Mo Bee remembers. “With the money I got from those two songs, I ran down to 48th Street in Manhattan and bought one of the SP-1200 units. And that’s where all of my work began.”

Mastering the machine

As his workflow on the SP-1200 developed, so too did Easy Mo Bee’s sound. “I got the idea to take the SP-1200 and turn it into a ‘band’,” he says. “A band has guitar, bass, drums, piano… so I’d take these individual instruments, put my ‘band’ into the machine and play back something original. That’s how we got a lot of beats, like on Machine Gun Funk by Biggie and Everything Remains Raw by Busta Rhymes. Anyone can loop but I created techniques on [the SP-1200] that nobody had ever used or was even thinking about.”

Nick Hook fondly remembers DJ Muggs and Cypress Hill applying a similar concept – this time with several SP-1200s. “The Cypress Hill guys used to put four of them up next to each other. There’s only 2.5 seconds of sample time per sample, so one would be the drums, one would be the bass. They would assemble a band of SP-1200s, basically.”

Grammy-winning Spanish beatmaker Cookin Soul, also a longtime user of the SP-1200, is another producer who accepted the SP-1200’s challenge to develop his practice. “I used to see Pete Rock with the SP-1200 and I was like, ‘Oh, I got to get an SP-1200’,” he told MusicTech in December. “But drum machines have no soul; you have to create the magic.”

At one stage, Rossum remembers, E-mu’s production team won the aforementioned debate, and the decision was made to discontinue the sampler in favour of more profitable ventures. “The orders kept staying constant though,” he says. “So we brought it back.”

It was during that brief fallow period that Wedge was asked why E-mu had discontinued the sampler. With no concrete answer to offer, Wedge jokingly replied off-hand, “because we don’t like hip-hop”. Inevitably, the ironic comment was taken out of context and circulated, much to his and his colleagues’ dismay. “It was so far from the truth,” Rossum says. “But someone picked this up and didn’t think it was a joke. One of the things I’m most proud of in my whole career is my modest role in the birth of hip-hop.”

A timeless classic, reborn

Back on our video chat, Easy Mo Bee demonstrates his process. He successively hits each of the buttons on his SP-1200 to demonstrate their respective contributions to the ‘band’: a snare, a kick, a hat, a Rhodes flourish, another chord.

“Now listen to this,” he murmurs as he triggers the kind of dynamic and immediate fusion of beat and melody that only decades of experience can muster. A demonstration of archaic technology this was not. “It’s just art, man,” he says modestly. “It’s art. The way you can take a bunch of random pieces from a song and arrange them such that they become a new composition. The style became a habit. And the habit is my sound. It’s the Easy Mo Bee sound.”

Rossum needed little encouragement to reissue the SP-1200 in all but its original form. “The moment we opened our doors at Rossum Electro-Music we got emails from people asking, ‘Will you bring the SP-1200 back?!” he says.

“We knew that people wanted an SP-1200, we knew they loved the sound of it. They loved the nature of that primitive technology. The choice then becomes: do you make something that has that primitive technology but uses today’s technology to fit the rest of the modern period? Or the flipside – which we chose – to actually reproduce the vintage instrument?”

For producers like Nick Hook, this was the right decision. “The limitations are the magic of the machine,” he declares. “Limitation changes the creative situation and the output of your music. The SP-1200 is the holy grail of them all. I’m curious to see what the next generation does, having only ever known unlimited sample time. Each generation breaks the rules in a different way. But these kids won’t have any rules to break.”

Cookin Soul agrees. “I listen to so much stuff that was created on that machine. The limitations are what makes it fun. It has to be fun. Because if you really want to get good at something, you have to spend a lot of time, and you have to love it.”

Despite so far resisting the pressure to reboot the E-mu SP series entirely, Rossum plans to continue right from where this reissue has left off. “My hope for the future is that Rossum Electro will continue in the drum machine world and that we can start making some modern innovations on top of what the SP-1200 is,” he says. “I don’t know what I’m going to do yet but I’ve got some ideas. Watch this space.”

For more gear features and reviews, click here.