Matt Lange – The MusicTech Interview

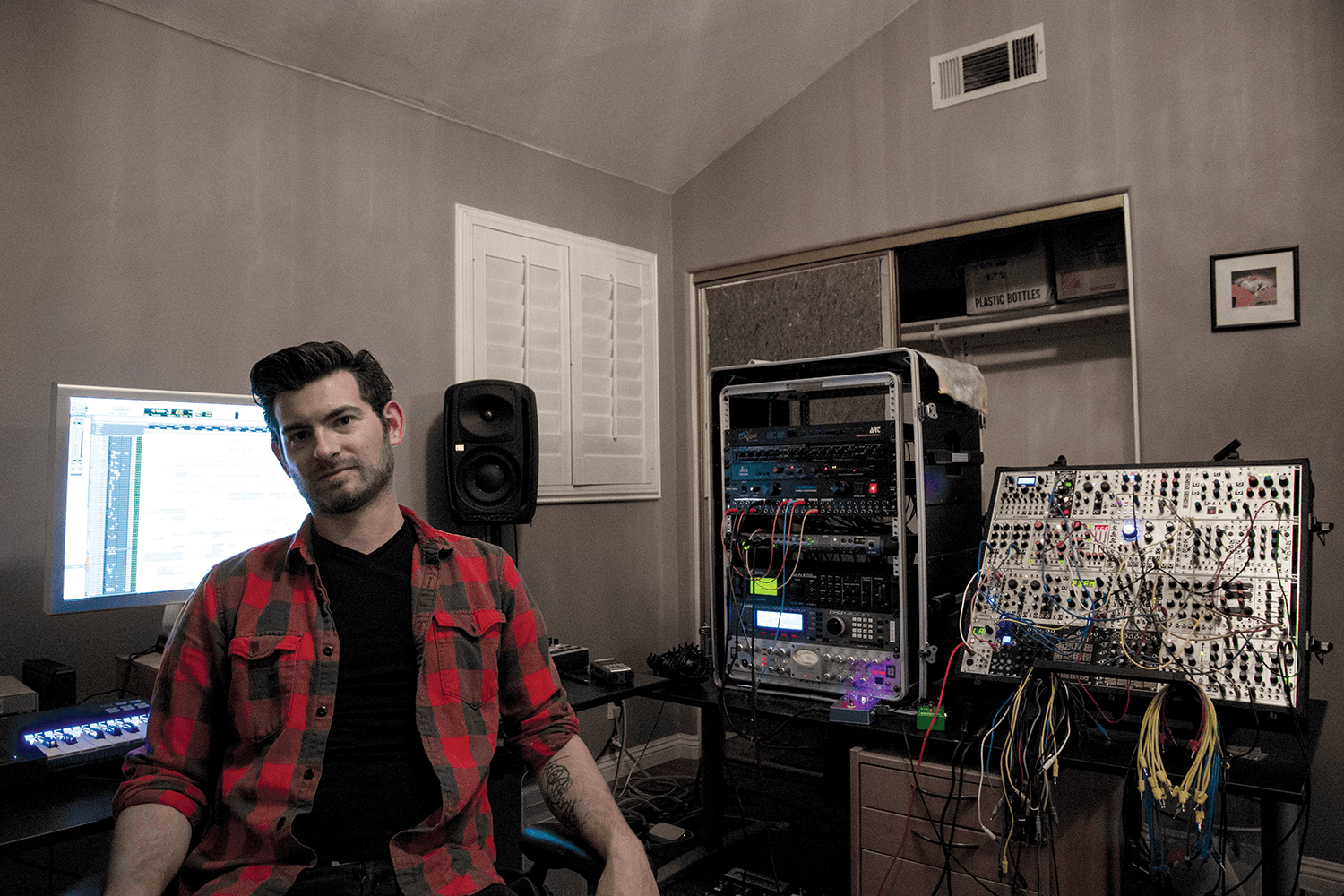

A graduate of Berklee’s Music Synthesis programme, Matt Lange carries the torch of innovation through his infectious love of technology and flair for sound design. MusicTech speaks to the experimental techno producer about his creative technology workflow and his newfound love of modular systems… LA-based producer/DJ Matt Lange was inspired by the aggressive industrial programming […]

A graduate of Berklee’s Music Synthesis programme, Matt Lange carries the torch of innovation through his infectious love of technology and flair for sound design. MusicTech speaks to the experimental techno producer about his creative technology workflow and his newfound love of modular systems…

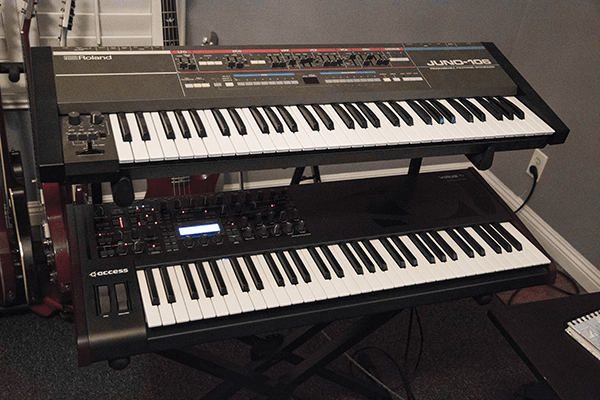

LA-based producer/DJ Matt Lange was inspired by the aggressive industrial programming of early Nine Inch Nails and Aphex Twin’s brutal contrast of ambient and jungle. Packed off to Boston’s Berklee College by his parents, Lange undertook a music-production course and began home recording on an old laptop. Introduced to BT by one of his college mentors, Lange worked as an engineer on the trance producer’s Grammy nominated album, These Hopeful Machines. He then began developing sample libraries before striking out on his own to create official remixes for The M Machine and Usher, while co-producing Glenn Morrisson’s platinum-selling progressive house album, Goodbye in 2013.

Self-produced releases arrived under the pseudonym Altered Tensions alongside the collaborative project Above & Beyond. Then, to his surprise, Lange was handpicked by renowned Canadian producer Deadmau5, who released the album Ephemera (2015) on his own mau5trap label. Both this and the following year’s Patchwork demonstrate Lange’s heavily textured production aesthetic, based on a love for analytical programming and an increasingly modular-based setup.

MusicTech: Tell us about your interest in electronic music…

Matt Lange: I was introduced to Aphex Twin’s Richard D. James album in the late 90s. Around the same time, Nine Inch Nails’ The Fragile came out and it really pushed me in the right direction. It combined orchestrated elements with cool electronic programming and songwriting. I pretty much grew up being a metalhead, so it was a combination of many different styles I loved. It really pushed me in terms of electronic music programming, production and the marriage of acoustic and synthetic material.

MT: Did you make music at this point?

ML: Yeah, I had this old Sony laptop and a version of Fruity Loops and Acid Pro, so I would program these awful – or maybe not so awful at the time – beats that I thought were that style. Then I’d bring those into Acid, record a bunch of guitars and make my compositions. I hadn’t got into synths yet; it was guitars and beat programming.

MT: What direction were you taking?

ML: When I first started getting into dance music, a trick that a few people taught me was to take a track you really like, put it at the top of your sequencer and emulate the arrangement. I wouldn’t copy the track, but I’d place markers wherever a change happened, like a hi-hat or a melody, and that would guide me. It gives you a roadmap. Even now I’ll do it, not so much in the same way, but I definitely analyse pieces of music that I admire, mostly because I can’t turn off the analytical side of my brain [laughs].

MT: Why did you take the Berklee course?

ML: It was the only place I wanted to go. I had to do college – with my parents, it wasn’t an option. I had this dream of becoming a pro skateboarder, but when I was 17 I tore all the cartilage in my ankle so that was the end of that. I was playing in a band at the time and doing a lot of the production at home using my laptop setup to record a bunch of demos. Using a very old version of Sibelius, I’d transcribe all these different parts for pretty much everyone to play. I’d bring them to my bandmates and they’d be like, “What the fuck man? We’re not going to do this – you just did everything for us!” I thought I was going to take an engineering course, but once I got there I realised that when you do that, you don’t really get to write any of your own music. You’re behind a console the entire time, which is great, but I’m a creative.

Then I found a major called ‘Music Synthesis’, which doesn’t exist anymore. It married a lot of the music production with writing for picture and sound design and was much more composition-based. It was amazing, because you could come out of that and have the tools to do anything on the production front these days.

MT: Plus you were recording at home at the time, too?

ML: When I was at school, you’d have to rent out lab time to use the computer systems and you’d only have two hours at a time. Everyone’s wearing headphones and you’re in this room with 20 other people – how is that productive? I was bartending, so I took the money and bought my own gear. Suddenly, there were no time limitations. I didn’t really have much of a social life; I’d go to class and then I’d be home working on my music all day long.

I learned how to handle very high-stress situations in the best way I could for my age and how to work and interface with the people at the business end. It was really a wake-up call.

MT: Tell us about your debut Ephemera on Deadmau5’s mau5trap label?

ML: I’d been releasing music with Above & Beyond on Anjunadeep for five years, and they’d put out a compilation album of various tracks of mine. Mau5trap’s A&R had heard a techno record I’d done and reached out to my management asking if I had any contracts. I had all these techno records just sitting on my hard drive and sent them six or seven files but didn’t hear anything for six or seven months. Then they hit me up on Twitter after hearing a track called Scorched Earth Policy and within two hours there was already a record contract. Essentially, it was for a single and an option for an EP, but I gave them an album instead, which allowed me to be more creative.

MT: It’s very electronic, but you start out of the box…

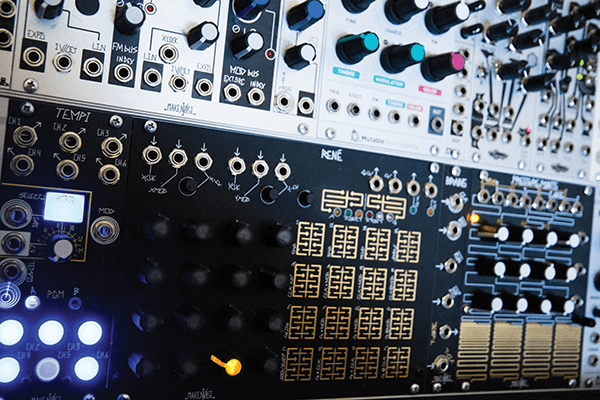

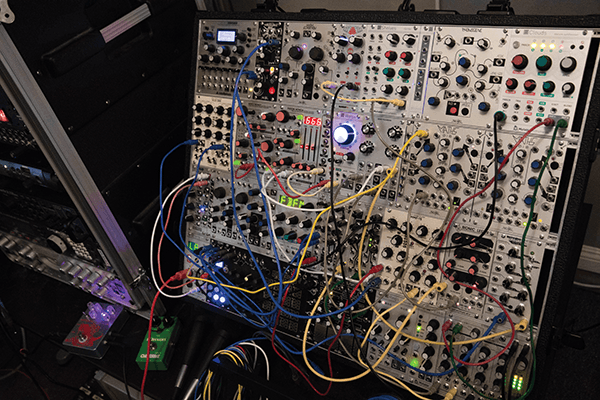

ML: Yes, the tracks that are more melodic, especially the vocal tracks, started on the Rhodes, but tracks like Inside My Head started on guitar. The club tracks started on the modular, and when I started putting the modular together about three years ago it really did transform the way I make techno music.

MT: How did you start in modular?

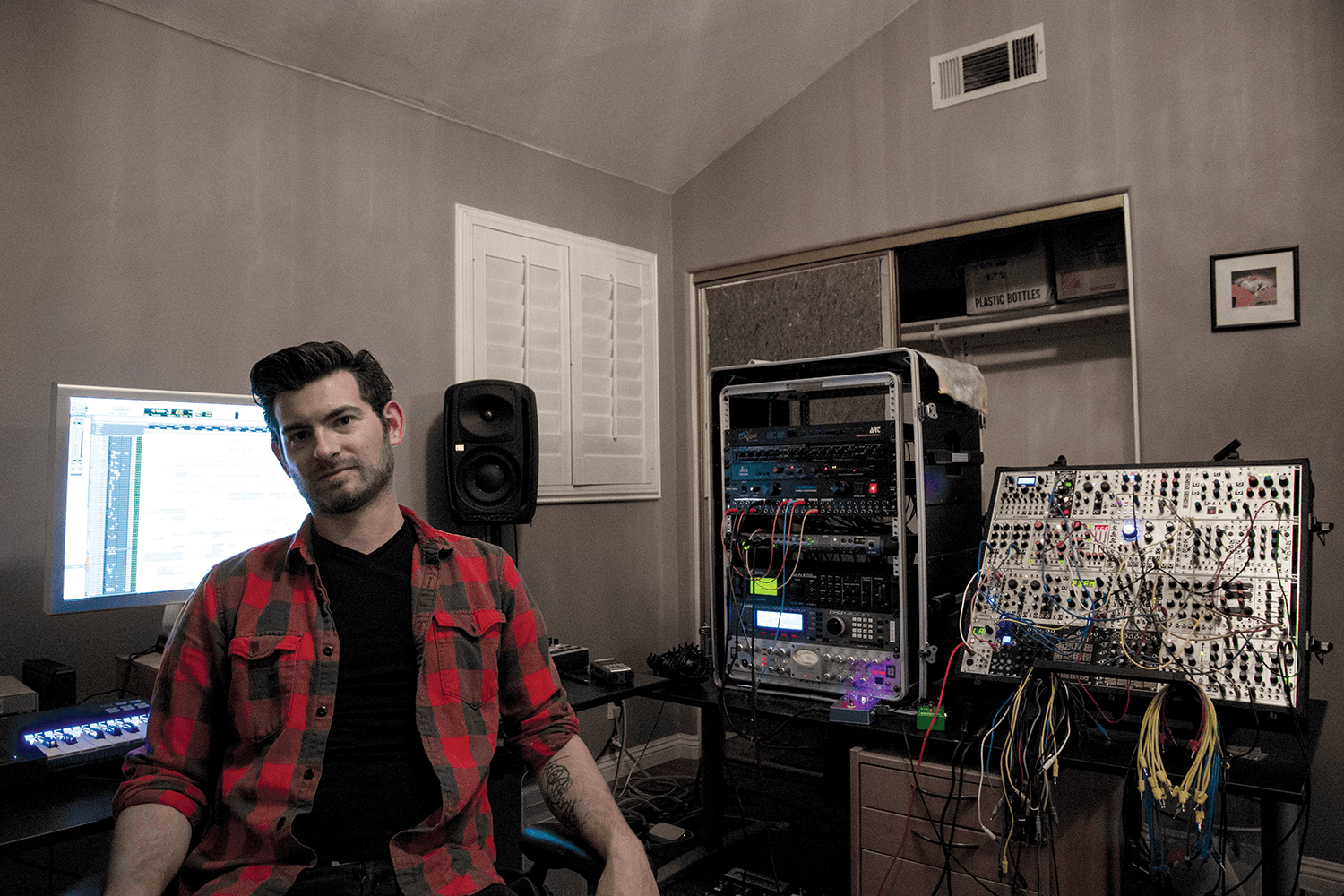

ML: The first time I really got introduced to it was at BT’s. Brian didn’t have one, but Richard Devine came and stayed with us for a couple of days and in the back of his car he had his first Doepfer synth. I remember, we were all sitting on the living room floor and he was piecing it all together. It was so new at the time for all of us, but ultimately, my friend Anthony Baldino brought his over and said, just touch it and you’ll understand. And he was right, it was immediate.

MT: What would you recommend to those looking to create a modular synth setup?

ML: For someone getting into modular, Mutable Instruments’ Braids is unbelievable in its versatility, and its sound quality is unmatched. So much of Ephemera came out of Braids, from the chords on Removes Me to the bass sounds on You’ll Remember Me and Ripples – the title of which was a filter that also came from Mutable Instruments. For more exciting things, I recently got a Cwejman VC02RM and a Cwejman MMF-1F, which sounds great and has the best resonance of anything I have here. Thanks to the VC02, I never need another analogue oscillator – this does everything in that realm better than anything I’ve ever heard. I’m a huge Cwejman fan.

MT: The ‘problem’ with modular is that, everything can be lost, right?

ML: When I’m in exploratory mode, so to speak, as soon as I find something I like the sound of I’ll hit record and keep tweaking. Sometimes, I’ll use the modular in a more directed manner, where I know I need a certain kind of sound and want to make it on a modular because it’s going to sound more interesting than doing it traditionally.

MT: Everybody presumed software was the future, but now hardware is big…

ML: Ultimately, modular is just another tool, but the ideas I’ll create out of the modular are things that I would never think of in a traditional musical way. And then there’s the tactile approach of being able to touch knobs, turn them and hear the physicality of electricity when you do it, and that is exciting. And of course, you can do things wrong.

You can take an oscillator signal, plug it into the wrong input of something else and it’s not going to be like a computer that says, ‘No, you can’t do that.’ You can do it and it might create a sound that you’re never heard before – and in terms of sonic exploration, that’s really crucial. I can’t use modular for everything by any means, but I always turn to it. And regarding the sound, there’s nothing in software that comes close.

A lot of modules these days are digital, but there’s always something to be said for a sound coming from outside of the box and going through a preamp, converters and audio going through iron transistors. On top of that, a lot of these module manufacturers are not big companies; they don’t have a board of investors and can do whatever they want. They might only make a run of 200, but you’ll get these really creative modules that you would never see in the software realm.

MT: So they give you unique options…

ML: Each system is different, so you can build your own Frankenstein synth based on your own needs and wants. For me, I’ll buy something if I know how it’s going to behave, or if there’s a more experimental oscillator. Dave Rossum just came out with a Morpheus Eurorack module that is the Z-Plane filter from the E-mu Morpheus, which is finally in a Eurorack format. I didn’t know how that was going to behave with some of the other things that I have, but I knew what it did and I love Z-Plane filter sounds from 90s drum ’n’ bass.

MT: When you’re using modular gear, is it true that you treat sounds differently?

ML: Oh yeah, 100 per cent. It sounds great on its own a lot of the time, but one of my favourite things to do with them is to run them through hardware. On the track Hyperwarp, I ran the bass sound from the modular through my Fractal Audio Axe-Fx guitar processor and used it for a lot of distortion, waveshaping and modulation. Recently, I got this fuzz pedal called the Devi Ever Big Distortion Sound Machine.

I was in a music shop and brought in this old Eurorack modular to trade in and saw this pedal that had two cats wrestling on it. I was like, Whoa, I have to plug this in, and when I looked closer, the knobs said Ruiner Gain and Ruiner Volume. So I plugged it in and it was like obliteration, so I brought it home and now it’s my favourite thing. I’ll send drum sounds, loops or programming out of Pro Tools through it and it’s a sonic annihilation of fuzz. For creating new sounds and getting ideas, it’s unbelievable.

MT: Tell us how you were called up to work with BT on his album, These Hopeful Machines…

ML: That came out of Berklee as the teacher I had during my senior thesis was also a mentor of Brian Transeau’s. After I graduated, BT was looking for someone to work for him in the studio he’d put together and my name came up. I flew down to DC, met with him and a month later I was driving down with everything I had in a Ford Focus. Previously to that, I’d released an album myself under the alias of Altered Tensions, which was very naïve and cute-sounding IDM, emulating artists like Richard Devine, Telefon Tel Aviv and elements of Squarepusher and Aphex Twin. That actually came out before I’d moved down to Brian’s.

MT: What do you learn from that whole experience of working with Brian?

ML: Erm, I’m trying to figure out the most political way to say this [laughs]. Right from the beginning, I got thrown into a very intensive working environment, which could be anything from dealing with major-label managers to executives. It was all very high level and I was only 21 at the time, so it was very much a sink or swim situation. It was long hours, overnighters, and although I lived five minutes away, some nights I didn’t leave at all. My technical role was as an engineer, but what came along with the job was everything but engineering.

MT: What’s your approach to using granular synthesis?

ML: I’ll use it in every way; I love it. Everything from making cloudy textures to ambient evolving pads – it’s great for that. For doing really cool time-stretchy clicky percussion, I’ll use Ophelia or cSound and just feed things into them and break apart the signal entirely. From there, you can pitch stuff up and down or make the grains shorter or further apart.

When you break a sound down to a granular level, you can reconstruct it to be anything else. Even if you granulise the hell out of a piano or a guitar, you get this evolving textural thing, but you know it’s familiar because it still keeps it character and still sounds beautiful and evocative. I just love how it can affect traditional sound and put it in that sphere of the ordinary and otherworldly.

MT: Sound placement is such an important component of instrumental music, could you give us some of your tips for panning?

ML: Double track. Instead of using a delay or panning plug-in, record the same thing twice and pan it left or right. It’s the oldest trick in the book and it sounds better. I love panning automation, but not a lot of people do it.

It’s also amazing what you can do with delay by offsetting a channel by five milliseconds. I don’t really like fancy plug-ins to do that kind of thing; I much prefer doing it by hand. A lot of times I’ll misalign things on purpose on the grid and do it visually. If I’m looking at claps or something, I like to visually see how all the different peaks of the claps are hitting at different points in time and pan all of them in different directions.

MT: Tell us more about some of your synth hardware?

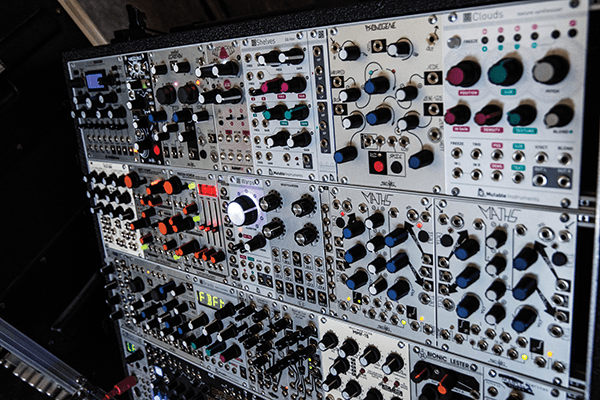

ML: I bought the Juno-106 entirely to make 90s drum and bass sounds. I got it for $200 about 10 years ago and I’ll use it periodically to make a chord or a pad, but my favourite thing to do with it is just make bass sounds, even though it’s a one-trick pony. I also have an Access Virus TI, which I don’t use very often. Until I got the modular, almost every kick drum, snare or pad used to come out of the Elektron Machinedrum MKII, but these days it’s mostly been retired, because the modular gives me more control.

MT: We noticed you use a Zoom Handy Recorder, for sampling, we presume?

ML: The last time I used it was to record a washing machine at someone’s house, which became a percussive texture for a track I was working on.

My newest favourite thing is that I have all these magnolia leaves outside my house. They’re really big, thick leaves and when you step on them they have the biggest crunch. So I recorded them at 96kHz, pitched the sound down two octaves and they sound like the clap of Godzilla.

The outside world has so many interesting sounds that we take for granted every day. If you put your musician ear to them, they’re so much more interesting than a fucking Saw wave.

MT: What outboard gear are you using for effects processing?

ML: Oh, the Eventide DSP4000 – that’s my favourite reverb box ever. I’ve never heard a reverb that sounds as lush as that. The first time I used it was at Berklee when we ran stuff through one of the polyphonic pitch-shifter reverb things on it called Genesis Worlds and got this giant reverb orchestral swell.

I made a whole track off that one recording. The other fun piece of gear in there is the Avalon VT-737, which I bought from Charlie Cooper of Telefon Tel Aviv six months before he passed away. One of my favourite albums ever is Map Of What Is Effortless and this is what they used to record a lot of that album. It’s a very special piece of gear to me.

MT: What’s your choice behind using Pro Tools as a DAW?

ML: Everything gets edited in Pro Tools, so it’s not like the music is being made out of the box. Once the sounds come in, everything gets arranged, destroyed and reconstructed in Pro Tools. So much of my workflow is audio. I don’t use much MIDI and nothing handles audio as well or with as much stability as Pro Tools.

Audio Suite is a huge part of my workflow – a lot of the time I’m moving through little clips and affecting things, whether it’s taking a snare and reversing it, throwing a reverb on it, flanging it, reversing it back again or pitching it up 12 steps, and I can’t do that with anything other than Pro Tools.

The only two VSTs I use are Reaktor for its granular synths – as far as granular goes, it is the best one – and the other, which doesn’t really count because it’s not a synth, is Kontakt. I make a lot of bass sounds on the modular and they’ll get retriggered out of Kontakt. I also use its orchestral and drum libraries for things I can’t make.

MT: So what’s behind your most recent single, the 10-minute track Unsettled?

ML: As far as the club music I do, I pretty much just make records that I want to play out at this point. I needed a track to brand the tour with, which is basically what Unsettled started out as. So this was my version of a larger-than-life techno tune, but because I’m me, I couldn’t do that and had to start putting vocals in and taking things a bit further [laughs]. Right now, I’m utilising my own label to release the more experimental music that’s inside my head, because that’s really where my heart lies. The plan is to put out a three-track EP every quarter, so I’m making an album but will be releasing it in parts. Each EP will be digital, and at the end of the cycle it will come out physically on vinyl, too. I polled my fan base, so now I’m accountable for following it up.