Neu!’s Michael Rother on forgetting his heroes and finding inspiration during lockdown

Rother drafted the blueprints for punk and electronica in the early 1970s with bands Neu! and Harmonia. And the multi-instrumentalist continues to make and perform music with relentless zeal. As a new boxset brings together his varied solo works, he reflects on his decades exploring new frontiers.

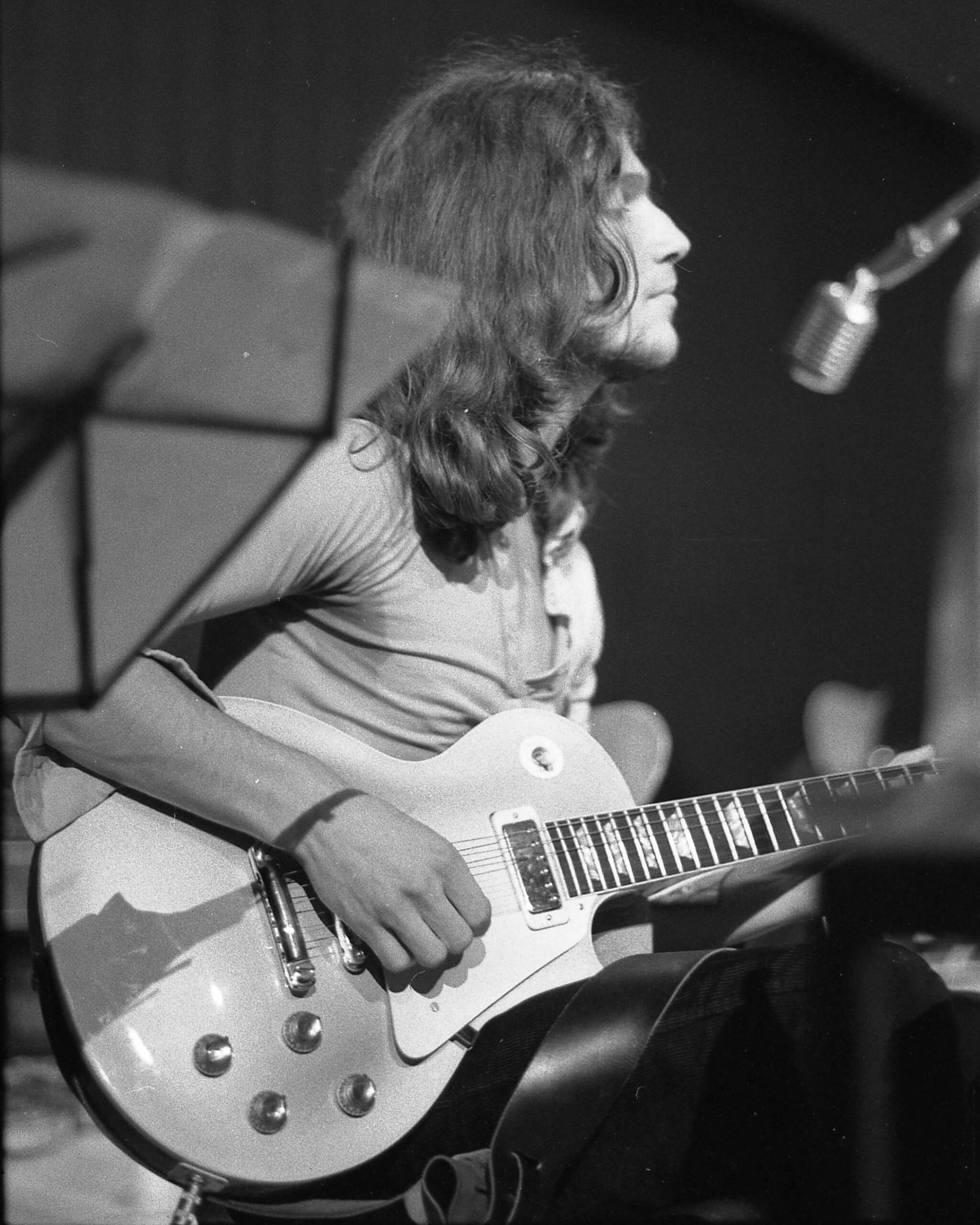

Image: Max Zerrahn

I think we were children of our time,” says Michael Rother, reflecting on the foundation of Neu. “The idea driving us was that we would dispense with all our heroes and try something completely different. Not a little bit different but totally different.” Apparent from the release of their groundbreaking 1972 debut, Neu – which means ‘new’ in German – were exactly that. The seeds of the band were sewn a year earlier, when Rother met drummer Klaus Dinger while the pair played in an early and unrecognisable incarnation of Kraftwerk, an act still in its infancy and far from the synth-dominated men-machines they would become. “It was a unique time,” says Rother. “There were a lot of innovators in different fields. In Berlin, we had this divided city, and we had the Wall and armed forces everywhere. There was a real atmosphere. I was influenced by what was going on, the military complex and the Vietnam war overseas. I was a conscientious objector, so I had to go and work in a mental hospital. It was the end of that period where I first met Florian Schneider.”

This meeting of minds would prove instrumental for Rother, not just in establishing a vast network of forward-thinking musicians but in solidifying the core principles that would drive him to create Neu.

“I went along with another guitar player who had been given an invitation to head into the studio and work with this band called Kraftwerk,” says Michael. “I went in and saw a young Ralf Hütter at his organ. I casually picked up a bass and we started jamming. I didn’t know anyone else who had that ambition of overcoming traditions and starting something new until I met Ralf. At first, we just threw around some melodies and parts but it was soon clear to all of us that we shared a common idea of a Central European melodic base. It was not related to [the then-dominant] blues. It was its own character.”

Building tomorrow

Born in Hamburg in 1950, Michael’s formative years rolled on against an ever-shifting backdrop: he was schooled in England, Pakistan and his native Germany. This changing scenery proved important in shaping his thought process, as he soaked up influences from diverse cultures and their accompanying musical genres. By the early 1960s, Michael’s love affair with British pop had blossomed. “I was enraptured by The Beatles, The Kinks and The Rolling Stones,” he says, “and then later by Cream and Jimi Hendrix. There was such excitement and creativity there, and this led to me joining bands myself and learning guitar. I was very melodic and so I was put into the lead guitarist role. That went on for five years maybe, during which I tried to copy those heroes of mine and stick to the rules.”

Before long though, Rother began to envision a world free from the conventions of pop songwriting. “When I got to about 18 years old, it dawned on me that I had to leave all that behind in order to find my own musical identity,” says Rother. To do so, he sought to make music that reflected the anxiety and tension of the times, and thus a more accurate portrayal of the human experience.

“I didn’t know what the future would bring, that was quite clear. My intention was to create something that was different to everything that had come before. It was a very ambitious approach. We were trying to push the erase button of our memories and discard all the influences we’d picked up over the years. The intellectual approach was to leave behind Anglo-American pop and rock structures, and to find a new way of expression.”

“They rode an MCI JH-24 tape machine into my studio in 1979 and it hasn’t moved since”

After the aforementioned stint with Kraftwerk, Rother and Dinger birthed Neu alongside visionary producer Conny Plank. Though sales of the self-titled 1972 debut album were low, the band’s influence grew via word of mouth, and their continued inquiries into thrilling new musical forms saw them pioneer key developments in modern music, including the motorik 4/4 beat, less reliance on conventional hooks, and some of the earliest examples of remixing.

“When we started Neu, it was quite clear to us that we wanted to create something unique, hence the name,” says Rother. “We were driven by the desire to be different and to create something that hadn’t been heard 10 times before. “Of course, it is difficult to re-invent the wheel,” he continues. “But with tracks such as Hallogallo, for example, the first thing I did when composing was to throw away everything I had learnt from those hours of finger practice and running through scales. The idea of piling harmonies on top of each other was discarded and, instead, we went back to simple single notes and tried to develop ideas that could be expressed with one note on one level.”

Many of the approaches pioneered by Rother and Dinger would go on to form the foundations of future genres, including electronica. “On the first Neu album, there’s only one track that has two harmonic levels,” says Rother, “Weissensee – I remember clearly thinking about whether it was necessary to have that harmonic change. But then I thought about it like breathing in and out, so the tension is released.”

Wunderkind, wanderlust

Following the band’s second album, 1973’s Neu! 2, Rother formed Harmonia with Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius of German act Cluster. That same year, the three retreated to a small village in Saxony to record music that would further build on Rother’s innovative ideals, and would win fans in Brian Eno and David Bowie. The pair would incorporate everything they loved about Harmonia’s music into the latter’s lauded Berlin Trilogy, with Eno describing Harmonia as “the most important band in the world”. “We knew Roxy Music and were quite thrilled by Eno’s words,” says Rother. “But Harmonia was really neglected at the time. We didn’t make much money and the albums didn’t sell well. So when this famous guy told us how much he admired German music – Kraftwerk, Neu and Harmonia – we were delighted. I was in love with what we did in Harmonia just as much as Neu. I was completely convinced of the music. It was always frustrating when the first albums came out and they didn’t get the attention they deserved. I guess people weren’t ready for them.”

Despite commercial indifference to both Neu and Harmonia, Rother pressed on in fascinating new directions via nine solo records, recently topped up by the release of new studio album Dreaming, featured in the second volume of his Solo boxset, which comprises much of his back catalogue.

“If you’d asked me last year

if I’d be releasing new music

in 2020, I would’ve laughed”

“The first record in the box is 1983’s Lust,” says Rother. “The name pertains to ‘wanderlust’, which means ‘joy’. It was very different to its predecessor, Fernwärme, which had a much darker atmosphere. When I started working on Lust, I had just discovered the Fairlight musical computer. It was revolutionary at the time and super-expensive. It let me introduce sounds that I couldn’t use before. That was a thrilling period. The Fairlight operated using a composing language based on mathematical equations and, for the first time, you could also introduce samples. It was very low quality, 8-bit. But it opened so many doors. There was a rhythmic page that allowed you to make interesting patterns spontaneously. Lust was dominated by that early dabbling with computer-generated sound. It was a very positive feeling.”

On follow-up albums Süssherz und Tiefenschärfe, released in 1985, and Traumreisen, released in 1987, Rother would double down on the nascent sampling and computer-based technology helping to upend musical traditions and create new ones altogether.

“On the next record, I continued to explore new technology to create music and discover new sounds,” he says. “I used an expensive reverb unit that I processed my guitar through on that album. It has a wonderful room to it, and you can hear that clearly on the track Süssherz. Making the next album, Traumreisen, I discovered digital synthesis with the DX7. I incorporated those sounds into songs such as Lichtermeer and the title track. I was amazed when I listened back to them recently. Despite being made more than 30 years ago, the sounds still hold up.”

The great adventure

Rother’s keen desire to harness new technology continued through 1993’s Radio and 1996’s Esperanza, on which he began using the Akai DD-1000 sampler and an early version of Pro Tools. “The final album in the Solo II collection, Remember, was started in 1997, and was a very different production,” he says. “I worked with Thomas Beckmann on that record. We had so much material but loads was left unfinished. After that record finally came out in 2004, my life took a different trajectory and I started working on film scores and playing live more, and I never returned to that stuff – until now.”

Rother found the time to return to this dormant material during this year’s lockdown. “I had the opportunity to go back and delve into the unfinished Remember material. There were sketches from 1997 to 2003. I started working in late March and listened to all the remaining recordings. I assembled the new record from these beginnings, added some more guitar and some new spontaneous elements. I’m really happy with how it ended up.”

The living museum

Has Rother’s personal creative space changed during the many decades he’s been working? “I am a living museum,” he says. “I have an MCI JH-24 tape machine that Conny Plank used. It was installed in 1979 and it’s on wheels. They rode it into my studio and it hasn’t moved since. As technology evolved, I started working on laptops mainly. I now have a living-room studio, which is my favourite place, as it’s the middle of my life. When I work on music, after two hours of fine-tuning a mix, it’s important to listen differently. I do that by playing the music while I’m in the next room making coffee. This allows me to listen in a different way to analysing every frequency coming from the monitors. It’s much more real.”

In terms of modern production, Rother oscillates between Cubase and Pro Tools. “I bought a Pro Tools system for my Mac during the 1990s, and mixed and mastered Remember with it. But then I started working on RME Fireface interfaces both at home and live, and that remains my basic set-up. I bought a Mackie mixer in the 1990s for live mixing. It looks like a piece of military gear now but it has travelled the whole world with me and still works. I have some effects units, and some notebooks with different versions of Cubase on them. I use an old version of Cubase when I play live too. I know my way around it. I don’t want things to be too complex. It works fine for me.”

Forward thinking

With another new solo record in the can and a boxset now on shelves, does Rother plan to

keep making new music? “If you had asked me last year if I’d be releasing new music in 2020, I would’ve laughed at you. What we’ve learnt is that you should never expect. Things happen and we react to them. I would love to return to playing live and at festivals. We played at Green Man Festival a few years back and it was remarkable. I miss that. We have some provisional dates lined up next year, at the Union Chapel in London and in Copenhagen in May. Let’s keep fingers firmly crossed that we can get back out there soon.”

What does the next decade hold for Rother then? “I don’t have to think about making new music now,” he says, “because I’ve just stepped back from this beautiful process of working on new music. It’s a bit like giving birth. After that, you want to concentrate on other aspects of life. My partner and I compose music together too, just for our own creative fulfilment. But, to be honest, I’d love to get back on stage right now.”

Michael Rother’s Solo II boxset, which features new album Dreaming is available now.