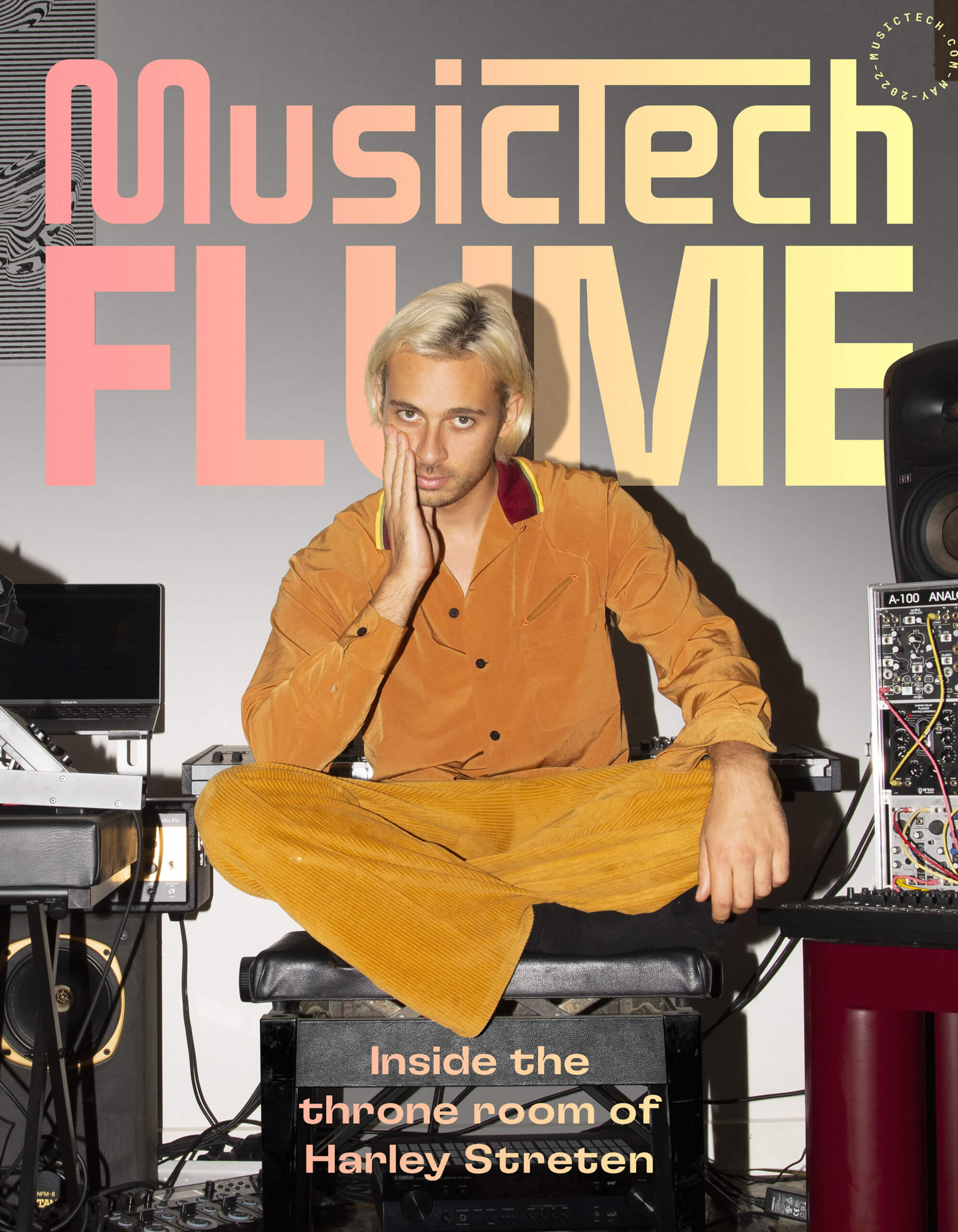

Flume: “Being a solo producer can be lonely. I try to make it fun with as low stakes as possible”

Following the release of his third album, Palaces, the Grammy-winning beatmaker brings us to the wilderness of rural Australia and into his throne room.

Image: Zac Bayly for MusicTech

Listen to Flume’s new album, Palaces, and try to imagine just how he conjured its supermassive sounds. Go on, we’ll even give you til the end of this article. You might be able to decipher some of them but certainly not the body-shaking bass parts in Get U. Not the mind-boggling chops in Escape ft. Kučka and Quiet Bison. Not the otherworldly textures on opener Highest Building ft. Oklou. Even Damon Albarn sounds unfamiliar in the album’s title track.

“I try to make things that sound unique. The paths that haven’t been trodden,” 30-year-old Harley Streten tells MusicTech when asked about his wild sound design. “There’s so much diversity on the record, you know? There’s a wide range of sounds and every song is quite different.”

Such an intricate, rich and abrasive sonic palette is not unusual for a Flume record. In 2012, Flume shook the electronic music scene with the huge, wonky synth parts, heavy beats and chopped vocals of his self-titled debut. He was soon thrust into the limelight and gained further fame for his genre-warping remixes of Disclosure, Lorde, Ta-ku, Rustie and more. Collectively these remixes have amassed hundreds of millions of streams on YouTube alone.

By the time his second album, Skin, dropped in 2016 with features from the likes of Vince Staples, Beck and AlunaGeorge, the scene had their ears locked on Flume’s frenzied productions.

Though Palaces comes 10 years after his debut, Harley isn’t celebrating this anniversary with a third album. “No, I just make stuff and it comes out when it comes out,” he says. “When I feel like I’ve got a strong body of work, I’ll just put it out.”

Harley’s most memorable moment of his 11-year-long career isn’t a release or award. Instead, it’s when he realised that Flume was a sustainable full-time project. “The first moment of being able to fully support myself, financially, from just making music was very cool,” he says.

“I used to work at Hard Rock Cafe as a waiter and I fucking hated that job so much,” he continues. “And then, when my first EP came out as Flume – I was making other music before that but more clubby stuff – the ball started rolling, and I started to get gigs. That was a huge moment to be able to say, ‘I quit’.”

It was a long time coming. Harley started producing electronic music at the age of 10 after discovering the 1999 music-making PlayStation game, Music 2000. “I was like, ‘Holy shit. You can make music on PlayStation?’” he says. The game whet his appetite for beatmaking.

“I went to a video game store and asked [the staff], ‘Do you have any music-making games?’ The guy recommended eJay,” he tells us, the 1997 music game for Microsoft Windows. “He was like, ‘If you want to come back next week, I’ll burn you a CD-ROM full of cracked music-making software’. I came back a week later and he gave me a demo CD of his music and another CD [of music software]. I’d come home from school and hop on my cracked DAW. I was always just doing it as a hobby.”

Harley mastered his craft during a worrying time for software developers. In the 2000s and early 2010s, online file-sharing was rife and software piracy was near impossible to prevent. Harley happened across plenty of DAWs and plug-ins to help him build on his Music 2000 masterpieces. It’s only recently that he started experimenting with hardware instruments.

“I know it’s illegal but, as a kid, it was amazing to have access to everything,” he says. “I did buy one piece of gear. It was the Korg Radias and I was so confused by it that I never used it. But now that I can afford it, I’ve got a bunch of hardware.”

As we geek out about the synths, modules and drum machines he’s collected, he becomes visibly excited, like a kid during show-and-tell.

“Ah man, I’m taking the fucking – have you heard of the SOMA Pulsar-23?” he asks us, enthusiastically. “We’re gonna figure out how to take that [on tour]. It’s like the devil made a drum machine. It’s not pretty [laughs]. You gotta get your hands on one and try it out.”

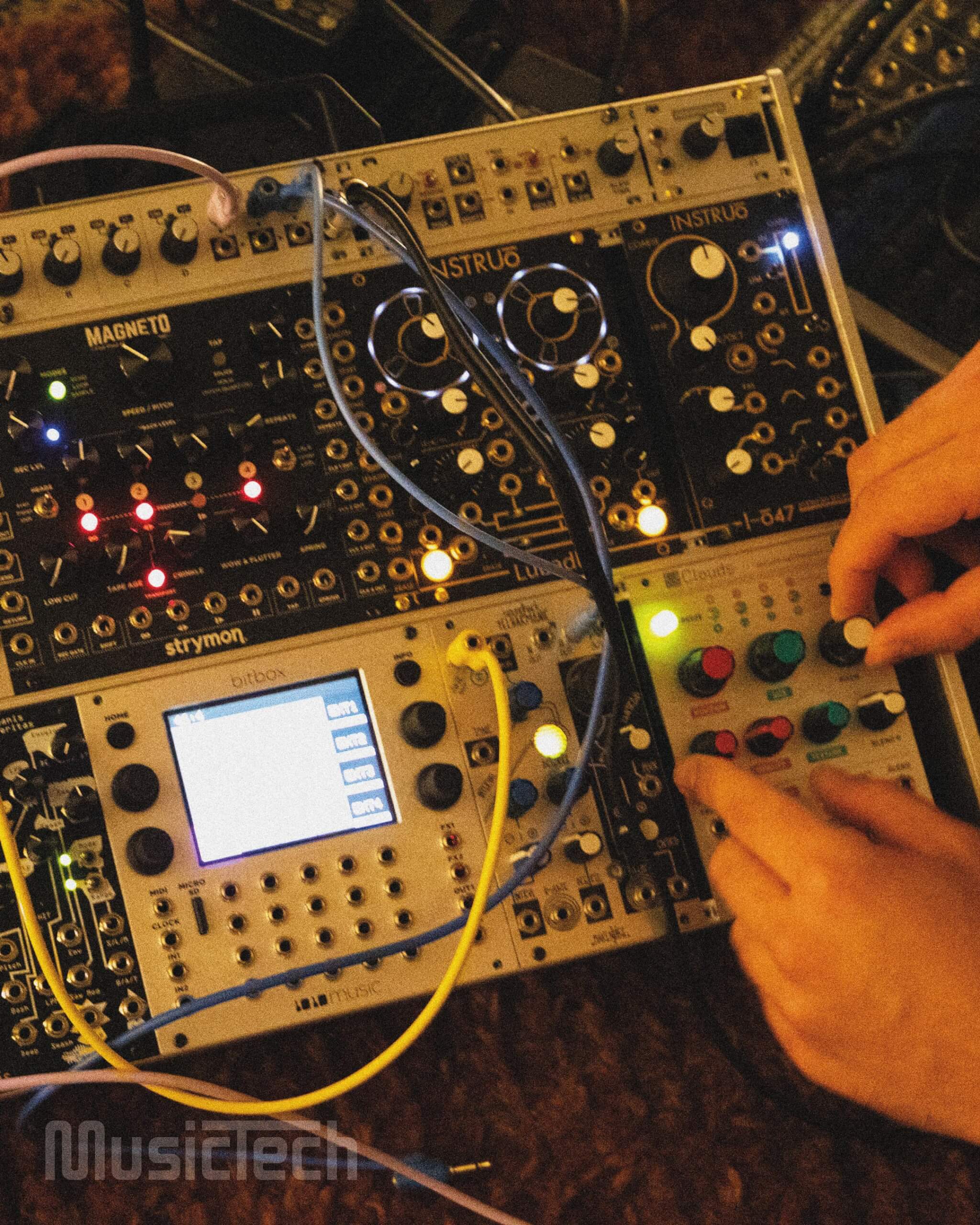

It’s no wonder Harley loves this aggressive beat machine – Palaces is brimming with hot bass parts, saturated kick drums and overdriven leads. Elsewhere, he’s jumped headfirst into the overflowing world of Eurorack modules and patch cables and has fallen in love with Sequential’s Prophet synth series.

“I’ve gone down the modular hole,” he says, with a laugh. “I have modules that do things I can’t do on a computer. I treat my modular synths like a guitar pedal effects rack. I’ll record myself messing around for 20 minutes then I’ll use software to cut up the sounds and warp them and take it from there.

“The Prophet-10 is the most beautiful synth,” he continues. “Everything about it: the sounds, the fact it has no effects, it’s just pure synth; I adore that. And then the Prophet X, which is not just a synth, it’s a ROMpler – you’ve got your strings and voices and all that. Those might be my two favourite things.”

Buried in the foliage of Palaces’ meticulously crafted sonics are ambient sounds of Flume’s homeland. You’ll hear the faint singing of birds in the introduction of the title track and subtle field recordings sprinkled throughout. Even though each track has its own distinct flavour, the producer sees Oz as the thread that ties the album together.

“I put all the pieces of the puzzle together and was able to dig into some sketches and complete them. The album came together in Australia and I wanted to incorporate my environment into the music because it was such a scatter of [material] from different years and different times.”

In 2020, Harley returned to Byron Bay, Australia, feeling uninspired after some time in California. He moved to the countryside, just down the road from his creative partner on the Flume project, Jonathan Zadawa, who has been working with Harley since before Skin, in 2015. The subtropical area Harley moved to is where he gathered foley recordings for Palaces. Living out of the city and in rural Australia offers a break from the “fast-paced life” and gives Harley the “simple, wholesome existence” he’s always wanted.

LA, it turns out, wasn’t quite right. “I wasn’t feeling particularly creative,” he tells us. “I’m quite a neurotic person; I put pressure on myself. And being a solo producer, it’s always a mental battle. One day, you’re like, ‘I did this amazing song, this is gonna be great’. The next day, you’re like, ‘I fucking suck, I made that one good thing, it’ll never happen again’.”

Harley finds comfort in bouncing ideas off other artists, either remotely or at the studio. For instance, he has worked with Kučka on three projects now – Skin, Palaces and 2019’s mixtape Hi, This Is Flume – and says he adores her “alien, sexy space lady, vocal tone”.

“She’s been on so much stuff,” he continues, chuckling. “Now I think about it, we always do stuff. When I find these people, some of them end up being lifelong collaborators.”

On Palaces, almost all the featured artists are female. Harley gravitates towards female singers “mainly because of where the vocal sits,” he says. “It allows me to take all the room down the bottom, all the bass and low-mids. And [Kučka’s voice] just kind of sits on top so nicely, with very little effort in EQ’ing.”

Harley recalls a magical moment when Oklou sent over her vocal recording for Highest Building. “When she sent that back, I was like, ‘Holy shit. This is amazing.’” The track was made mostly over FaceTime, and the two artists are still yet to meet in person.

Harley compares remote and in-studio collaboration, telling us that “in a studio session, there’s pressure to keep things moving. So I end up doing safer things that I know will work. When it’s remote, I can do things that I don’t know if we’re going to work and take my time.”

Still, Harley is fond of studio sessions for the intimate experience with other artists. So long as it’s not uncomfortable – as it almost was with Damon Albarn.

“I was nervous because I was a huge fan of his. I had a bunch of ideas prepared that I wanted to play him,” Harley says. “I played the first idea, he wasn’t into it. Played the second idea, he was nonchalant about it. I must have played 20 different drafts and he just wasn’t into anything. And I was like, ‘Oh my god, he hates everything I’m showing him’. I was sweating so much.

“It was the second-to-last idea that I played him when he said, ‘Yes, this is it’. And I was like, ‘Great, thank fuck’. Then we sat together in front of a little MIDI keyboard, he played some chords over it and just hummed some stuff.”

The result of this nerve-wracking session is Palaces’ title track, a melancholic closer to a mostly hyperactive album.

Palaces, like Flume’s other albums, comprises loose beats with vocal chops scattered atop unpredictable melodies and chords. These stylistic choices come from his discovery of J Dilla, Flying Lotus and Jai Paul, artists who aren’t locked to a four-to-the-floor groove. Once he heard Jai Paul’s 2010 track BTSTU, he realised, “‘this is what I want my music to sound like’.”

But now, after spending so much time dabbling in off-grid rhythms, does he miss his time as a dance producer? “Every six months or so, I get really excited about house music,” he says. “Then I make a song or two that’s at 120bpm, 130bpm, four-to-the-floor.

“I got really inspired when lo-fi house started happening with Ross From Friends, DJ Seinfeld, all those people. It was terribly mixed but melodic and something about it was so exciting.”

Harley reveals that his lo-fi house project may soon see the light of day, telling us he’s “got an album’s worth of house music ideas” he wants to put out. “I was thinking about starting a completely different project. Or I could put it out as Flume, I guess some of it probably does sound a bit Flume-like. Whenever I make house music, I’m locked in. It’s a whole area of production I don’t get to experiment in and be creative in because it’s just 4/4. But it’s also the best rhythm in the world, at least I think so.”

Listening to his past remixes, you can tell Harley has a soft spot for dance music. Eiffel 65’s 1988 chart-topper Blue (Da Ba Dee) got the Flume treatment after the Aussie producer was “having a few beers with a friend one night and slapped it into Ableton Live”.

After having fun chopping up the track, he reached out to the Italian group to see if they’d send over the stems – to which they obliged. “I got that record when I was a kid; it was one of the first CDs I ever bought,” says Harley. “So it was cool to see them totally down to share the parts. And then hearing the parts – I’d never heard the vocals separated and it’s kind of an iconic track,” he adds with a laugh.

Harley approaches remixes much like his original material. Mostly, it’s a case of taking the vocal hook from the original track, modulating the pitch and slicing it up over the top of his own beat. His remixes are iconic, often becoming more well known than the original track. Just take a look at his spin on Disclosure’s You & Me – it’s clocked hundreds of millions more streams than the original and has even been covered by marching band, MEUTE. But such reverence can sometimes become a burden.

“I felt like there was a lot of pressure on me because I had a lot of successful remix work and everyone wanted remixes from me,” he says. “But I didn’t have ideas constantly and I didn’t want to repeat myself; I developed ‘remix-phobia’. But now I’m doing them again, not putting pressure on them, and just having fun.”

His early days of producing also had Harley flipping samples and vocal lines from old records. Though he misses imparting the sonic artefacts of vinyl records into his music, his sampling skills almost got him in hot water.

“I’ve got into dramas with sampling stuff in the past; putting samples in tracks and not telling the label about it because I’m like, ‘No one’s gonna know’. Then someone on Reddit figures it out. It can get messy.”

We speak about our favourite sampled music for a few minutes, including Bomfunk MC’s 1999 track Freestyler and Hilltop Hoods’ Nosebleed Section from 2004. “Fuck, I really need to get back into sampling,” Harley says with a grin.

So much has changed for Flume in the 10 years since he released his debut album. His novel sound has inspired a generation of producers and landed him in the studio with his idols. He’s set to tour the world this year for the third time, he won a Grammy in 2016 – “the bigger the award, the better”, he jokes – and has an ever-growing fanbase.

But, as his production style evolves with each album, it feels like he’s just getting started. He’s maintained the childlike spark that he had when he was playing Music 2000 on the PS1. As Harley settles into a quaint lifestyle in Australia, we may yet hear more of Flume’s eJay-inspired masterpieces. Perhaps we’ll even get that lo-fi house record – so long as he enjoys making it.

“I try and keep it fun. That’s the main thing – just making it fun with as low stakes as possible.”