Robert Glasper: “90 per cent of what I’ve released is one-take recordings. I don’t like to waste that energy when I feel like I’ve got the one”

The Grammy-winning producer on Black Radio III, scoring Bel Air and jamming with J Dilla in Detroit.

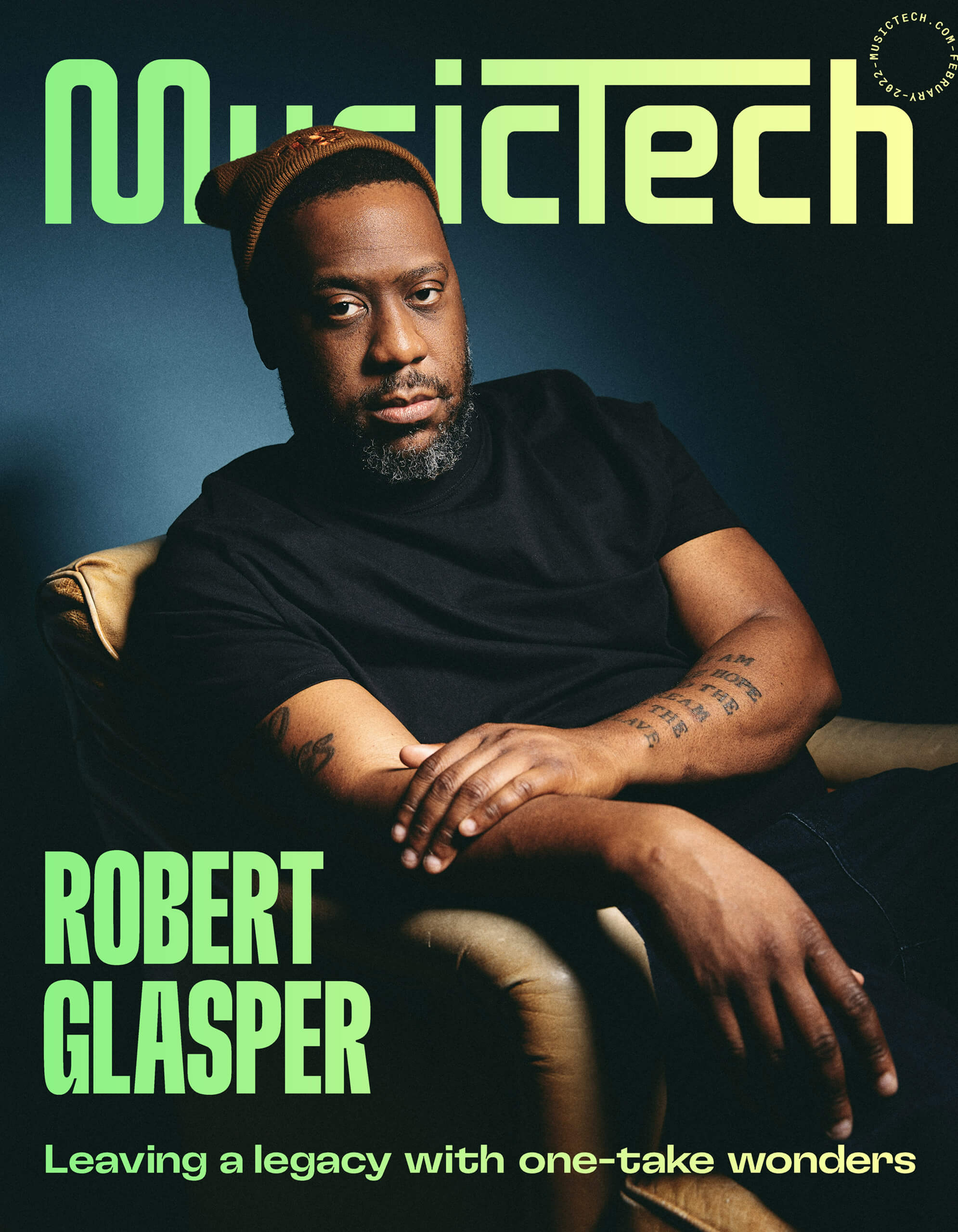

Image: Jonathan Weiner for MusicTech

Robert Glasper is wearing an ampersand T-shirt that celebrates the late Gil Scott-Heron. It lists the artist’s accomplishments: “Poet, Musician, Activist, Influencer and Rock n Roll Hall of Famer”. The Scott-Heron family posted it to Glasper a few weeks ago, after he contributed to the celebrations around the musician’s induction into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame last year.

“He’s a superhero,” says the multi-Grammy winning producer, recalling when he and Mos Def had Gil Scott-Heron guest on their show at Carnegie Hall a few months before his passing in May 2011. “He was such an important activist and artist. It was great being in the presence of someone who was so fearless and so unapologetic about standing up for social justice. He did it in such a cool way. Sometimes it was artsy, sometimes it was in your face – and that’s art.”

The same could be said for Glasper’s latest edition of his Black Radio albums. Black Radio III runs the gamut from the powerfully political on tracks such as Black Superhero to his gorgeously arranged cover of Tears For Fears’ Everybody Wants To Rule The World with Lalah Hathaway and Common.

The album begins with Amir Sulaiman’s hard-hitting poem In Tune, which contains a lyric that feels like the perfect subtitle for the whole endeavour: “We don’t play music, we pray music.”

“Music means so much to me and to us,” says Glasper from his pandemic-constructed studio in Los Angeles, where he moved after 23 years in New York. “That’s how I give thanks to the ancestors on whose shoulders I stand. That’s how I grieve through things that are happening in the world. That’s how I love. When I’m playing, I’m meditating. That lyric was spot on – music is all things that is prayer.”

Glasper got an early taste of art and creativity at the turn of the millennium, when he spent two weeks in Detroit with J Dilla and Bilal. “Me and Bilal were in college, living in New York,” says Glasper. “He did his demo in my dorm room. Jimmy Iovine (Interscope) signed him – of course, he then dropped out of college – and the first producer they had him working with was Dilla. Bilal graciously brought me to Detroit.”

This was late 1999, early 2000, and what followed was a masterclass in production. The trio would go to the studio and just jam for, say, six hours. After they finished, they’d get in Dilla’s Range Rover and drive around listening to the whole session. Then Dilla would take a few demos that were almost a complete idea and add “a few bells and whistles for a few minutes”.

The road testing extended to parking next to the studio, tweaking a mix and printing off CD-Rs – from a console kept by the door specifically for this purpose – before checking the mix on the car stereo and going back in to make more changes.

“When the night fell, we’d go to a club,” says Glasper. “[Dilla] would give the DJ the few things he thought were ideas and the DJ would play them, not mixed, not mastered, not nothing, just straight-up raw. In all kinds of clubs – I mean dancey clubs and I mean strip clubs. We would be on the side of the stage and we’d see the reaction of the audience, which is an amazing thing to do. That gives you a temperature, you know, if you’re going in the right direction or not. If you’re trying to rock a club, what better way to see if you’re on the right path than go watch ’em.”

The producer had been hired to make two tunes with Bilal, with one – Reminisce – selected for Bilal’s 2001 debut album, 1st Born Second.

“I watched it happen in real time,” Glasper says of the 4am session. “Watching J Dilla make a beat in 15 minutes was one of the most extraordinary things. Someone’s process is where you can tell if they’re a genius or not.”

He mimes Dilla picking a few records off the shelf and recalls him asking Bilal, “‘If I put them together to make one bassline could you sing over it?’” He’d pull four notes from one bassline, three notes from another, two from another still.

“What?!” says Glasper, deep in the memory. “How do you even hear what that’s going to be? Then you put it together and it sounds fucking crazy amazing. That’s why I am like, ‘The genius is in the process’. Seeing that made me realise what kind of person I was dealing with – a savant. It was an amazing experience.”

Glasper played piano on the other tune, which remains in the vaults. “His process is kind of like my process now, which is probably where I got it from, I don’t know. It’s just jamming and letting all the ideas fall through.”

The making of Black Radio III was inevitably different to 2012’s Black Radio and its 2013 follow-up, both of which won Grammy Awards. “My whole idea was always to be in the studio with the artists, to bounce ideas off each other and to come up with beautiful mistakes that lead to some other porthole of creative things.” Of course, in 2020, global realities required a shift in workflow and process. “When the pandemic hit, I thought, ‘This will be a challenge but let me do it’.

“So many artists were depressed, not feeling like making art,” says Glasper. “Other people felt it gave them something to do, to write. That’s what made Black Radio III different from the jump – it was a different world.”

Glasper worked with songwriters to send ideas to vocalists, sometimes firing over two or three sketch ideas at a time. “That kind of process I never did previously,” he says. “I’d do that for a film score but not for Black Radio. But some people weren’t feeling creative so I had to send them more ideas.”

Some of the recordings began in the usual way: jams. Glasper’s engineer Keith ‘QMillion’ Lewis would be in the studio and various musicians would come by, including drummer Justin Tyson and bassist Burniss Travis, who was in LA at the time working with Common.

Robert Glasper Experiment drummer Chris Dave was in town doing a session with Adele along with primo bassist Pino Palladino. They dropped by too. “After the session with Adele they came over here and knocked out two joints,” says Glasper. He mailed bassists Derrick Hodge and Thaddeus Tribbett the files and they added their parts from home. It was a creative response to a tricky situation.

Many of the lessons Glasper picked up during those early days with Dilla and Bilal proved pivotal in the Black Radio series. The beautiful third album possesses a timeless quality that opens and closes with Glasper’s world-famous piano lines that create acres of space for other musicians and vocalists to shine. It’s cut through with golden-era feels, that of 90s boom-bap and of the neo-soul age in which Erykah Badu, Jill Scott and D’Angelo were making their first records.

The Black Radio series features covers of classic hits across a range of genres. In Glasper’s third iteration of Black Radio, he put his spin on Tears For Fears’ 1985 worldwide hit. He heard it on the radio on the way to a session with Lalah Hathaway and instantly decided that Everybody Wants To Rule The World was one for the album. He asked the vocalist to take a look at the lyrics, had the arrangement in his head by the time he arrived at the studio, and recorded it in one take.

This is his ideal workflow, in the same vein of iconic R&B and soul records that were recorded in one pass, such as Roberta Flack’s The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face and James Brown cuts like Papa’s Got A Brand New Bag.

Lalah Hathaway’s cover of Sade’s Cherish The Day on the original Black Radio was recorded in one take – “the soundcheck actually”, Glasper says. And their one-take version of Jesus Children Of America on Black Radio II won a Grammy for Best Traditional R&B song.

“I don’t like doing extra takes for no reason,” he says. “I don’t like to waste that energy, especially when I feel like that’s the one. Literally, 90 per cent of what I’ve done is one take. Even if the solo is less good than another solo, if the spirit was better on the first one, I’m more into that.”

Shine, Black Radio III’s third track, came from a jam in which the usual roles had been reversed: Glasper was on drums and his drummer moved over to the Moog One. The music just rolled out and Glasper later added bass, keys and piano.

He’s been collaborating with Keith ‘Qmillion’ Lewis since 2009 when the engineer worked on Double Booked. Glasper says he met Qmillion through his work with Chris Dave’s “amazing live R&B band” Mint Condition. “[Qmillion] is not a producer that oversteps,” says Glasper. “He can troubleshoot, he knows things before they happen, he knows me artistically. When he sends me a session, it sounds mixed already. Half of the battle is done once he’s recorded it.”

Once the music is recorded, Glasper goes to Qmillion’s house for some critical listening. “He has four different types of speakers from big to small, and we’ll see how it sounds on each one. Everything sounds good on huge speakers. It’s banging! It’s crazy! Normal people don’t have those speakers. We go from big speakers to headphones, to different headphones. I have all kinds of headphones, cheap headphones all the way up. You have to step into the listener’s world to see what they’re gonna hear. Sometimes I make a change after a month of listening. I get away from it, then I’ll come back to it when I have fresh ears.”

After a month, Glasper might send additional notes: add a bit more low-end; take some reverb off the piano, dry it up a bit; add some mid-range to this part of the vocal. These are all “little bitty things that you hear after you’ve been mixing,” he says. “I know for sure if I [only] go to his house one time, that’s not ‘it.’”

The worldwide turmoil during the recording of Black Radio III had Glasper dealing with the decisions that face all artists – the degree to which he addresses social issues around the globe.

“You have to choose to acknowledge it at all, acknowledge a bit, or acknowledge it too much,” he says. “When a lot is happening in the world, people turn to music to escape those things. George Floyd, Donald Trump, the pandemic, police shootings. People don’t want to be reminded – they know. But some people have a responsibility to say something and I feel I’m one of those people.

“I thought, ‘Let’s go ahead and address the elephants in the room at the very beginning’”. Hence the Amir Sulaiman poem and the single Black Superhero, which was broadcasted on a huge screen in Times Square, New York. “Boom. Let me just do it. After that, other subjects come into play, it’s a listening album. But the first two songs are coming at you.”

Black Superhero was inspired by a lunch lady who worked at his junior high school. “I didn’t live in the right neighbourhood to go to the school I went to. The lunch lady would pick me up from the gas station by my house and drive me to school every morning for a year – my mom couldn’t take me all the time. Looking back, she was a superhero. It allowed me to go to a better school, and I was able to go to an even better high school because of that. I hope Black Superhero inspires that snowball effect.”

The track includes scratches from Jazzy Jeff, who created the original theme to US sitcom The Fresh Prince Of Bel-Air. Glasper recently scored the remake, Bel-Air, with fellow musician, producer and composer Terrace Martin. Glasper also collaborated with Martin on a more concrete project: his new outhouse studio and drum room that they built together during the pandemic.

“Before I had this room it was different,” says Glasper. “I would score from Logic Pro and had a lot of premeditated ideas. Then I’d get into this studio with the cats and flesh out those ideas. When I got this room it became less premeditated and more just in the moment.”

They’d pull up each scene and read the notes from the spotting sessions – Zoom calls with the director, music supervisor and editor, during which they’d watch episodes of the show and stop at each scene that needed music.

“Normally a day or two after, we do the score, vibe together and come up with something on the spot. I come up with things faster on the fly.”

Alongside composer Nicholas Britell (Moonlight, If Beale Street Could Talk), Glasper also co-scored Winning Time: The Rise Of The Lakers Dynasty, the upcoming HBO documentary series on the LA Lakers. “It focuses on the 80s era, when they first drafted Magic Johnson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar; the Jerry Buss era. It’s amazing.”

Gil Scott-Heron paved the way for a generation that would combine their artistry with social commentary and activism. Now, Robert Glasper and Terrace Martin are following in his footsteps, developing routes for younger artists to access new worlds of music.

“We were able to craft hip-hop beats in a way that worked for the [Bel-Air] score. For someone who’s never scored but knows how to make beats on the fly, with different emotions attached – that’s something that a lot of young kids can get into.”

Part of the problem, says Glasper, is the image that comes to mind when people think of a composer. “A lot of people think of a composer as the nerd who has to know how to score for a 100-piece orchestra and has to be able to write music,” he says. “You don’t.

“People don’t think they can fit in that space because nothing in the world tells you that you can step into that space. Me and Terrace being who we are and how we roll, it’s gonna look like that.”

It’s a sentiment that Black Radio’s creative forebears, including Gil Scott Heron and Dilla, would no doubt salute. Robert Glasper is flying the flag for the music, the culture and the process.