Amon Tobin: “Get lost in the power of your limitations”

The prolific, ever-changing artist on learning from Ben Burtt, sampling and why he hates the term “sound design”.

Being a prolific artist is one thing, but being prolific and endlessly inventive is something few achieve. Amon Tobin comfortably falls into this latter category, his music consistently embodying a sense of adventure, discovery, and unknown.

Tobin’s music is difficult to categorise or describe in a conventional sense. It’s a testament to his desire to keep challenging himself, and to push the latest technology to breaking point in search of new sounds.

“I’m just curious more than anything, really. That’s it,” Tobin tells us from his studio in Los Angeles. His curiosity is largely focused on the edge cases, using technology in ways it was not intended.

“It’s not that I’m bored and I’m like — how do I keep myself interested? It’s the other way around. I’m just really fucking fascinated by this stuff, and I can’t find the hours in the day to explore all the possibilities of it,” he enthuses.

This fascination has defined Amon Tobin as an artist, with a conceptual approach weaving through most of his oeuvre. His 1997 debut Bricolage took the anthropological concept of misunderstanding aspects of different cultures and reordering them to fit one’s own worldview. This translated to him taking larger chunks of audio and assembling them into a patchwork of sound. It’s a process he describes as “music design rather than sound design.”

1998’s Permutation was even more granular, deconstructing and reassembling tiny slivers of sound from disparate sources and fusing them into something cohesive. Then 2000’s Supermodified delved further into heavy processing and transforming recorded sounds. There’s more of what most people would term “sound design” – a phrase Tobin bristles at.

“Online, [people] will be like, “oh, dude; I love the sound design on this tune”. And most of the time, I don’t know what people are talking about because anything is ‘sound design’. It’s just changing the shape of whatever you’ve got,” he explains.

“I blame the software manufacturers. I really do. The interfaces these days suggest we’re doing vital scientific work. They’re like graphs and charts, and we’re just making music. But I think we’re fooled into thinking that we’re navigating nuclear submarines or something!”

Tobin early works were primarily constructed with Akai hardware samplers – from the S1000 to S01 and later through to the S6000. But it was the 2004 release of Native Instruments’ powerful software sampler Kontakt that allowed him to delve deeper into the possibilities of manipulated audio.

“It was a real watershed moment because it was suddenly so much easier to do what you wanted to do,” he says. But he wasn’t particularly interested in just speeding up the creation process.

“I was trying to find new, difficult things I could do with Kontakt, trying to then see how far I could go within that platform rather than doing what I was already doing with the S6000 quicker.”

Tobin sees this development as a natural extension of his earlier experiments in sound recording. He explains: “The idea on Supermodified, for example, was to try and make playable instruments out of these recorded sounds. The only way to do that effectively was to synthesise them so they behaved as modelled instruments that I could interact with and play rather than triggering samples. Because if you think of a sampler, traditionally, you might have various layers of velocity, but they’re static forms, static sounds.”

This evolution continued with 2007’s Foley Room, taking sound effects made for film and games and bewilderingly turning them into music.

His 2011 LP ISAM (‘Inverted Sounds Applied to Music’) pushed him further into complex synthesis and advanced manipulation of field recordings and found sound. He also brought the record to life with an accompanying, awe-inspiring 3D audiovisual live show – a mind-melting sci-fi spectacle with an underscore that was as much mechanical as musical.

“If we’re talking about ‘sound design’ as a basis for music, ISAM is the furthest I took that whole scope of interest,” he says.

“You really don’t need a lot of gear. You need to be interested. Curiosity is the key.”

It’s perhaps little surprise ISAM sounded so futuristic. During the record’s production, Tobin would regularly visit George Lucas’s Skywalker Ranch, home of Skywalker Sound. He used the facility as a sonic brains trust, drawing on the experience of legendary sound designers and foley artists like Ben Burtt, one of the key people behind the beguiling sounds of Star Wars and Wall-E.

Around that time, he was getting into the Kyma sound design language and became fascinated by modular DSP-based sound creation. “I learnt about things like spectral synthesis and granular synthesis and the aggregates of all these different types of synthesis that I could piece together and use to make what I wanted,” he says

So how exactly does he model instruments from real-world audio recordings?

“It might start with something like a spectral analysis of a sound,” he begins, “It might be to take a Foley sound that I recorded and analyse it, separating the harmonic components out from the non-harmonic components. The harmonic components would be constituted of sine waves – kind of an additive process. So you’d have a fundamental frequency, and you’d add the sympathetic harmonics to a point that approximated the harmonic profile of the sound that you’d recorded. Then the non-harmonic sounds – which can’t effectively be modelled through a sum of sines, as Kyma might describe it – would be modelled with noise, for example.

By separately modelling the transients – the noise-based, non-harmonic sounds – and recombining them with the harmonic sounds, he is able to create cohesive sounds.

Sometimes he layers audio recordings of the sound source over the top to enhance the transients that are lost during this analytic process, giving a neat blend of the original and the approximated sounds. Once the characteristics of the instrument are determined, it’s then a case of mapping parameters to a suitable controller environment, like Kyma.

“If you think of pressing on a guitar’s string, there are so many variables, like the moisture on your finger; not just where you’re pressing it. Then every single time you play, there’s a different resonance and a different tension.”

He then maps as many of those parameters as possible from the synthesised sound to a Kyma controller, for example. He explains: “I would say, ‘OK, maybe the Z-axis on the Kyma controls the amount of resonance, and the Y-axis controls the change in timbre, and the X would be the pitch.’ So I could put my fingers in a sound and play it like an acoustic instrument.”

Despite his adoption of technology, Tobin’s desire to keep pushing the envelope is honed more by self-imposed limitations than the endless possibilities of continually collecting more gear.

“I try to limit myself by not having too many toys to play with because you can do so much with so very little. Getting to know a little piece of equipment intimately is so rewarding,” he says. But once he’s learnt the intended function of a piece of equipment, he takes greater delight in finding ways to use it not as intended.

“That’s a really lovely journey to take with anything, even with software,” he tells us.

“Get lost in the power of your limitations – that’s where creativity lies. That’s what makes you interesting.”

Recording history is littered with happy accidents; Otis Redding’s scorched Motown vocals from the mics being too close, Grandmaster Flash inventing scratching, DJ Pierre stumbling across the acid house sound when pushing a Roland TB-303 to its limits. However, Tobin actively seeks out the accidents, and his modus operandi has set him in good stead for over two decades.

Hitting a purple patch in 2019, Tobin released another three records on distinct themes: Long Stories (primarily made with the Suzuki Omnichord), Fear In A Handful Of Dust (minimalist soundscapes and intricately sculpted sound) and Time To Run (a hard rock record under his Only Child Tyrant moniker).

He actively strives to take the more difficult and time-consuming path when making music, because it’s ultimately more rewarding. However, his approach is at odds with technology’s promise to endlessly make out lives easier.

“I try and rail against this idea of convenience being the primary driver of technology because I feel it’s anti-creativity. Faster, quicker, easier is the idea – and that I feel like that isn’t it,” he tells us.

Tobin has an alternative outlook: “The idea is to allow you to push different frontiers. Once something is made accessible, then new frontiers change – that’s all. So it doesn’t mean that you keep doing what the fuck you were doing before. And I just have more fun using hardware than software in general. I think everybody does.”

2021 will see him release another two records, kicking off with West Coast Love Stories under his new Stone Giants project. This new moniker focuses on songwriting and his own beautifully hushed vocal delivery, presenting him with yet another exciting challenge.

“It’s very new for me to sing, so that took a big part of the production space on this record as well. It’s more to do with songwriting and trying to understand harmony, trying to get my head around things like that. I wanted to see what I could do with very simple elements stripped down, and so composition was more of a focus,” he explains. It makes for a beautiful listen, weaving his usual manipulated audio trickery with acoustic guitar, soaring synths, and soundtrack-esque ambience.

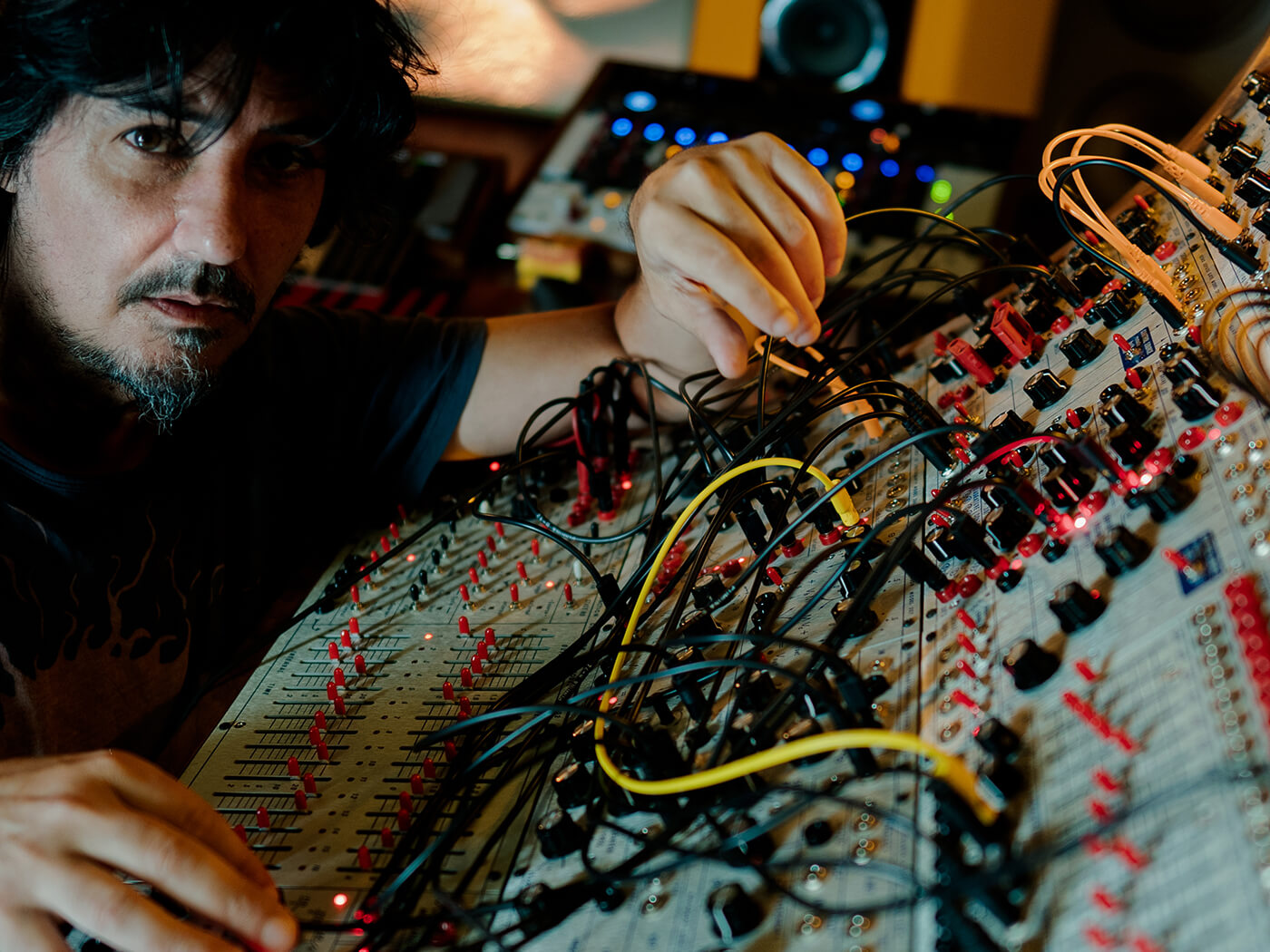

In terms of specific gear on the record, he continues to delve deeper into his fascination for all things modular. The stunning Haken Continuum Fingerboard ‘three-dimensional’ controller and modular synth was one of many key components that features therein.

“Edmund Eagan who made the Continuum, he’s built a very powerful synthesiser behind that controller – The EaganMatrix, he calls it – and it’s this fucking super-powerful synth engine. One of the things it can do very well is model acoustic instruments and to some extent vocals as well. So Metropole uses sounds from the Continuum for voice, for example. I also love simple things like Buchla and Eurorack stuff. I use a lot of resonators in Eurorack. I love things like [Mutable Instruments] Rings; it’s a beautiful module, a beautiful resonator that models strings very nicely. I think A Year To The Day might have been done with a lot of that. I’ve had a lot of fun modelling things like woodwind instruments with hardware. They’re much easier to do in software, but more fun to do in hardware. So I enjoy making feedback loops between things like very nice Sherman filters and short delays and seeing if I can make that kind of embouchure change happen between the feedback loop and the filter.”

The real inspiration that other artists can take from Tobin is not his ability to generate unusual, unheard, original sounds, but more his method for getting there.

“I always feel silly giving advice. I can say that it’s been helpful to me to not look at things as functional for the most part; to look instead at things as a discovery window. So if you’ve got very few resources, don’t get hung up on how long it takes you to do something that you would imagine would be relatively simple for somebody with a much bigger studio. If you think about it, B.B. King was doing sound design,” says Tobin, referencing the blues guitarist’s famous cigar-box guitar

“He knew what he wanted to do and he didn’t have the means to do it. So he found ways to approximate something in sound that he was after,” he continues.

“So I feel like it is more useful to think in those terms than to think about equipment and specific access to hardware or software. Get lost in the power of your limitations – that’s where creativity lies. That’s what makes you try and escape your limitations. That’s what makes you interesting.”

He concludes, “So if you only have a mic and your voice, listen to people like Jamie Lidell and what they can do with their voice and microphones. It doesn’t matter if you just got a DAW and a microphone. You really don’t need a lot of gear. You need to be interested. Curiosity, I think, is the key.”

West Coast Love Stories by Stone Giants is out now on Nomark.