Giles Barrett Interview – All aboard the good ship Soup Studio

Moored on the River Thames is Lightship95, a beautiful big red ship that plays host to Soup Studio – a full-fledged recording studio and live room. MusicTech speaks to mix engineer Giles Barrett about what the studio offers its clientele… Guitar player-turned-bass player Giles Barrett was still at university when he started playing with folk/indie […]

Moored on the River Thames is Lightship95, a beautiful big red ship that plays host to Soup Studio – a full-fledged recording studio and live room. MusicTech speaks to mix engineer Giles Barrett about what the studio offers its clientele…

Guitar player-turned-bass player Giles Barrett was still at university when he started playing with folk/indie pop band Hexicon. He then picked up the production bug having been assigned to produce indie rockers The Maccabees – an experience that motivated the fledgling mix engineer enough to set up his own studio at The Bunker in Whitechapel.

Forced out by high rentals, Barrett then met Simon Trought at Soup Studio in Brick Lane and began working alongside him in an engineering capacity. However, gentrification came calling once more, leading the Soup team to studio hop until Trought, remarkably, found a custom-built recording studio on Lightship95, a vessel moored on the Thames and kitted out by previous owner Ben Phillips.

Located at Trinity Buoy Wharf in East London, Barrett now works with a team of engineers on the boat offering live band recording and post-production. Mixing, sound design and mastering is also undertaken in Soup Studio’s purpose-built, analogue/digital recording facility, which has hosted the likes of Julian Cope, Leo Abrahams, Roots Manuva and a host of other artists for labels including 4AD, Domino, Island, and Universal.

You were initially a bass player?

I was a guitar player as a teenager, but I stopped playing music when I started recording it. I met The Maccabees when I was at university, and that’s when I started recording professionally. They were a cut above other student bands, so I hired out a room at the Biscuit Factory in Bermondsey, cobbled together a bunch of gear and recorded them because I thought the guys were a bit special.

How did your interest in production evolve?

I became more interested in recording than playing because I wasn’t that good at playing piano or guitar when I was a teenager. I remember listening to bands like Massive Attack and thinking, “How the hell did they manage to do that?” So I studied production at university and did some bedroom recording for my brother using Cubase, its really basic two-channel audio interface package and an Audio-Technica microphone.

How did you come to work on Lightship95?

Not a lot of London studios can afford a big live room without their rates being pretty high, so when gentrification arrived we stumbled on a chance to move to the Lightship, which was a no-brainer. The previous owner, Ben Phillips, had already been using it as a recording studio, but wanted to move on and had done a fantastic job of gutting the whole ship.

The control room used to be the diesel tank and the live room was the engine room. He had to cut out huge amounts of steel before he could even start thinking about building the internal walls, soundproofing and doing shock absorbing treatment to decouple the room from the hull.

In what way is it more affordable than a bricks and mortar studio?

We didn’t come here because it was cheap, and although Ben could get more rent out of a non-studio business, he still wanted it to be a studio. For us, it’s about security and separation – we don’t have neighbours who are going to have any noise issues, something that always used to plague us.

The ship is moored at Trinity Buoy Wharf and the owners have written into the lease that businesses that rent from them have to be used for cultural purposes.

What are your separate roles as a team of producers/engineers?

We all have individual characteristics as producers. The way we divide it depends on the best interests of the project and the client. Wherever possible, we’ll help on each other’s sessions, because it’s nice to offer a hand if you’re working with a nine-piece band, but everyone’s got their own tastes and musical backgrounds. There are four producers here, so anything that comes in is going to attract one of us.

Are you all equally competent when it comes to mixing and mastering too?

Yes to mixing, but not necessarily mastering. Simon specialises in mastering, but the rest of us prefer to take a project up to the mixing stage and have it mastered by a mastering engineer who can provide fresh ears, which could be Simon if he’s also been involved in the mixing stage.

How did you go about soundproofing and inserting bass traps in this sort of environment?

In some ways it’s easier and in others a lot harder. You have to pay much more attention to decoupling the internal room from the steel hull, because obviously if you bang on a piece of steel you’re going to hear that at the other end – in this case, the whole boat.

Once you’ve put industrial rubber feet round the wooden frame, it makes things easier because the mass of the steel then acts in your favour as long as you’ve got a sufficient gap.

Do you think this environment lends a unique sound to what’s recorded here?

Every room is different and there’s no such thing as perfect treatment, but we have made particular efforts to capture a certain type of unique sound. Part of that is the echo chamber, which Simon built in the old studio and we had to have here as well. It’s quite small, just a tiled room, but we put a couple of AKG 451 mics in there and the sound smacks off the tiles.

Some people will put a speaker in their echo chamber, but we leave the door open so we’ve got the drums at the other end of the room going round a corner, then a door and into the echo chamber to get that length of decay. We love the sound of that, especially for drums, but it’s cool for lots of things.

Not many young producers may even be aware of what an echo chamber is?

It was the original technique for studios to get reverb. Some used a metallic-sounding big space, like an old empty grain silo or big tiled room, which if they were big enough you could put a speaker at one end and a pair of microphones at the other and the sound reverberated around the room giving you natural reverb.

A lot of those techniques were replaced by plate reverbs, which were a similar principle with a metallic plate echoing. We’ve got one of those as well, and people are more familiar with those because plate reverbs are used a lot for vocals, but echo chambers sound a bit more spacious and natural than a plate.

If you’ve got Altiverb or one of those other plug-ins, you’ll see recreations of a lot of classic reverb chambers used in other studios.

What mic techniques do you employ to get different results from live recordings?

We really specialise in bands playing together. When you’ve got a bunch of different musicians in the room, it helps that the room is well treated, but we’ll make use of anything that has a figure of eight pattern to take advantage of those dead spots around the sides of the mic.

When I first started recording jazz, I thought I’d have to separate people off a lot, but with most jazz bands we’ll use four Coles 4038 ribbon mics, because we can line up the whole horn section in front of those, have them slightly side-on to the drums and you have just the right amount of separation without having to use screens.

They’re my favourite mics for drum overheads as well, although they’re not really bright enough for modern vocals.

You have two drum stations, based on Rogers kits from the 60s and 70s?

We’ve got a Rogers drum kit, which came to us by chance but we love it. It’s got quite a small 20” kick drum, but that’s got so much punch. We do have a 24” Slingerland kick drum too, which is lovely for producing a round, subby, warm sound, but a lot of drummers have been shocked by the power of our tiny Rogers kick drum.

Presumably, people can always bring their own gear?

We totally encourage people to bring their own gear of, course, but it’s nice to have a really solid backline. We’ve got a good selection of Fender amps, a few top-quality guitars and some keyboard instruments, like piano, Wurlitzer and Hammond.

I know that some drummers come here because they don’t have to bring anything, but I think it’s important for bands to have their own specialised equipment if they want a specialised sound. It’s better if someone brings a £100 guitar that they can really play than use a £10,000 guitar that they’re not comfortable with.

Your analogue tape machine is a real feature of the studio?

We’ve got an Otari MTR-90 MkII, which is a 24-track, 2” tape machine and we use that on about half of the tracking work we do because there’s nothing really like it. One reel of tape costs about £300 these days, so because budgets are tight we keep a good stock of old tape that’s well-maintained and just re-use it. It’s nice to use tape when recording an entire band, but I particularly like using it for drums.

What does the Otari bring to the sound that’s so special?

I don’t think any plug-in has really emulated tape compression, but it’s not just that, there’s also something about the way that tape captures the sound. The way we have it set up is very seamless; the tape machine goes between the desk and our Pro Tools interface and we’ll do a test in the morning to find out how many samples the tape machine is delaying the signal by.

The reason we do that is because we might want to record tracks 1, 3 and 5 through tape and 2, 4 and 6 straight to digital, so we’ll just delay the digital signal by the same amount as the tape signal. Also, because we’re running audio through tape at the same time as we record it into Pro Tools, artists have the benefit of not having to wait around for us to rewind the tape or test it.

Does using tape help when it comes to mixing and post-production, because you’re originating a more complete sound?

That’s part of it. As much as possible, we’ll try to get the material sounding how we want it to as it goes directly into Pro Tools. Particularly since moving to the ship, but throughout my years of recording, I’ve found that my typical Pro Tools plug-in count on any channel has probably gone down from eight to one.

Having used digital processing, was there a point at which you realised analogue is actually the best way to go?

It’s something I learned when I recorded my own band last year, because half way through recording the album, we got hold of a Warm Audio WX76, which is an emulation of a classic ‘76 outboard compressor. I started recording all the vocals through it because it has a really transparent sound and you can push things really hard without hearing any obvious distortion or artefacts.

When I came to do the mixing, the tracks that were put through the 76 were ten times easier to mix than those that hadn’t been, particularly as we were doing quite complex vocal production using group vocals and double-tracking.

So having that sound already sitting in the mix as soon as you’ve tracked it saves a lot of time, because when you leave everything to the mixing stage you’re often second guessing and just hoping things work out. Tape comes into that category as well; it just helps tie the sound together and gives you a sound that you’re happy with right from the start.

You mentioned favouring Pro Tools as your DAW?

Yes, Pro Tools 12. I’ve used Cubase and Logic too, but we do a lot of editing and I like to encourage people not to play to a click unless they need to. I think there’s a tendency these days for people to assume they have to play to a click and it’s nice to tell them they don’t.

When I’m editing, I’m not thinking it needs to be bang on the grid, I edit with the idea of it sounding good, which is the only goal. Pro Tools allows me to do that and it’s streets ahead of the other DAWs in terms of editing.

What speakers are you using?

Our main set is the ADAM A77Xs, which we absolutely love. Financially, they were a downgrade from our Focal Twin 6Bs, which were pretty good, but the producer Leo Abrahams hired the ADAMs in for a session here and we were pretty blown away. I’d never heard that level of detail in the control room and the bass really stood out.

Going to listen to speakers in a speaker showroom or another studio is really not the same as listening to them in your own studio, which is why it’s quite scary buying speakers, so we were really lucky Leo brought them in. We also have a pair of Auratone MixCubes for mono checking.

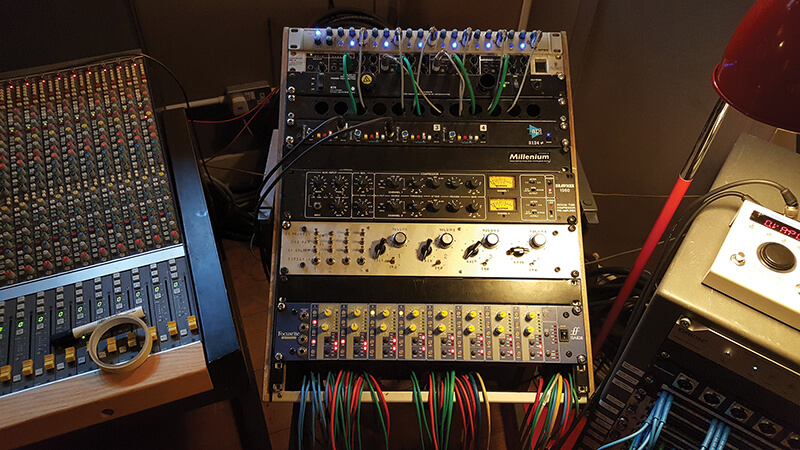

What other outboard are you using?

We’re into our analogue tape echoes. Again, EchoBoy is amazing and does pretty accurate replication of the Copicat and Space Echo hardware, but I know exactly how the software’s going to behave and when you’re sending the Space Echo into feedback it’s never exactly the same each time.

It’s also about the interaction with the client. If you tell them you’re going to use a plug-in, that’s fine, but if you ask them if they want to control the repeat rate while you adjust the intensity and nudge the Space Echo to the edge of feedback, they’ll prefer using the hardware.

We’ve got a Roland RE-5 digital delay/reverb and a dbx compressor as well, and I’d definitely like to get my hands on a Teletronix LA-2A or Pultec compressor sooner rather than later. There are lots of people making analogue outboard these days, so there is more affordable high-quality analogue gear around than ever before.

You have a few hardware synths too?

Yes, we’ve got a Roland RS09 organ/strings synth, a Korg M500 Micro-Preset, an Arturia Microbrute and the Korg Volca Keys. We do get rock bands coming in that use synthesisers as a lead instrument and we find that the Micro Brute is particularly flexible for lots of different production styles.

The centrepiece of the main studio is the Calrec S2 48-channel mixing console?

It’s a fantastic desk with six SSL-style stereo compressors and huge levels of connectivity with everything that’s coming from the patch bay. I love using an analogue desk and because the Calrec was designed for broadcasting, everything is duplicated.

It’s amazing what’s happened to the price of desks like these. It was new in 2002 for £250,000 and kitted out for a Sky broadcast truck, but we picked it up last year for just £10,000. We just got a technician to spend a day on it and after that we were very happy.