Ask Abbey Road: John Barrett talks committing and how to use the Altec RS124

The engineer explains how to get great results from classic gear.

The Altec RS124 compressor, one of the “treasures” of Abbey Road.

In the final part of our extensive interview with Abbey Road engineer John Barrett, we discuss how you might record The Beatles in 2019, how to use classic gear such as the Altec RS124 and how much freedom a recording engineer should give a mixer.

Gui: In your opinion, who is the most influential engineer or producer of all time?

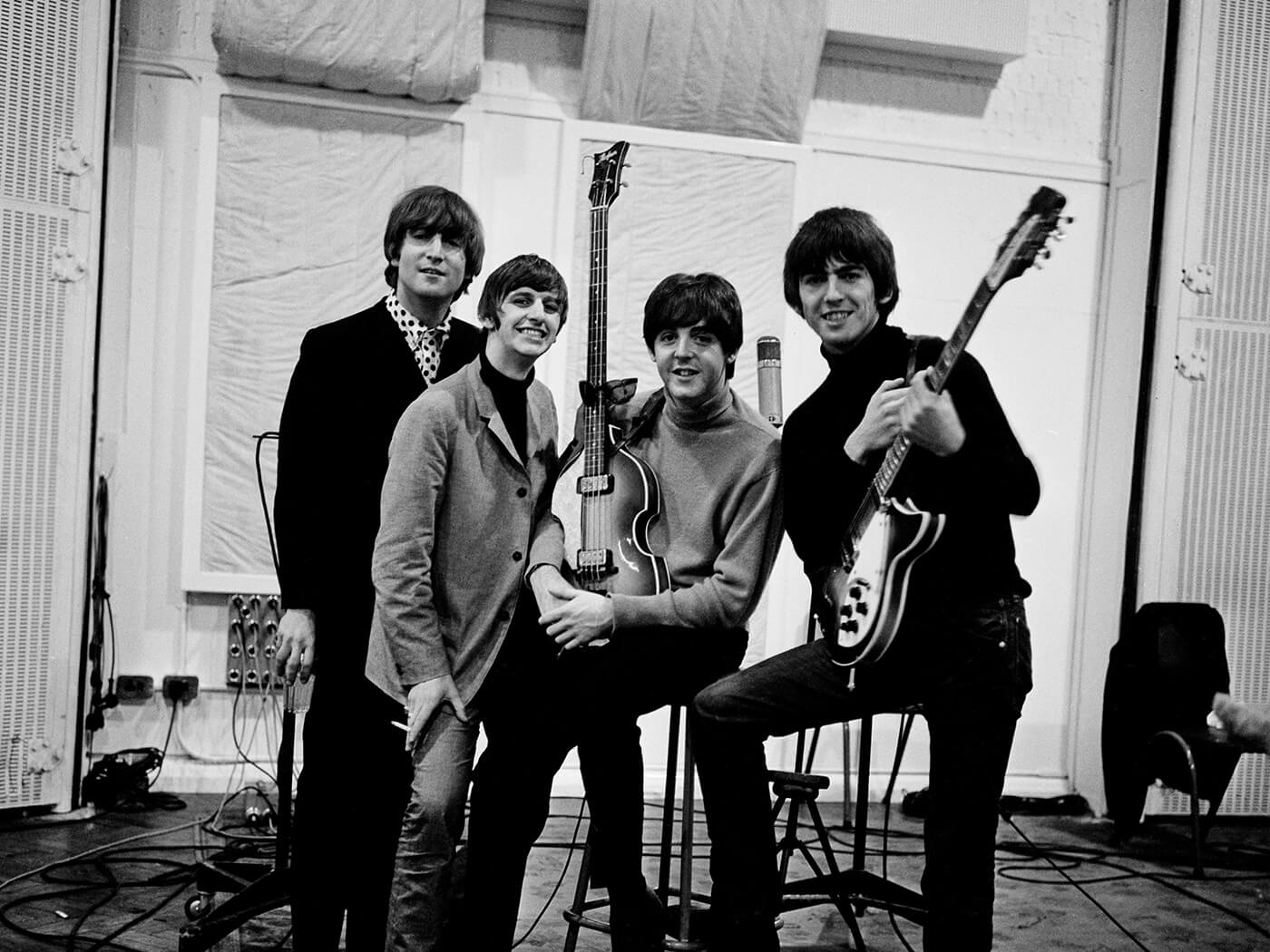

John Barrett: Someone who I think is a bit of an unsung hero is Norman Smith, the engineer for The Beatles up until Rubber Soul. He started with Please, Please Me in 1963 and then went through to Rubber Soul. And after that went on to produce Pink Floyd. To have the development in sound that The Beatles had between those two periods – you’re talking two years – and what he did from an engineering point of view to get Rubber Soul, that’s pretty amazing.

That’s a massive leap in technique and the sounds that he created. Obviously, George Martin was a big part of that, too. But as far as engineers go, I think Norman Smith is often overlooked. I never met him, but he sounded like a charming, unassuming guy as well.

Joel: Who’s the most impressive producer you’ve worked with and why?

JB: I find it very difficult to single anyone out. I’ve been incredibly lucky working here; I work with so many people across so many different styles. You can learn something from anyone that you work with, even if it’s that you don’t like the way that they work. That’s still a learning experience.

You learn different approaches. It’s fascinating seeing how some producers are really hands-on, and others are less hands-on. Or it might be they have a different manner with the artist, or they become more involved with the songwriting, or more engaged in the arrangement. So you can pick up lots from different people and the way they approach the work and dealing with the artist.

For example, I’ve never been able to get a satisfactory sound out of the Altec RS124, which is one of the most famous treasures of Abbey Road. It’s been used at some stage on every single Beatles record, but I’ve always been a bit uninspired by it. I was working with Ken Scott, who used it back in the day with The Beatles, and he showed me how to use it. It was interesting because I would never have used it in that way.

He was hitting it really hard, making it do a lot of compression. And I was looking at it going, ‘Really?’ Then you stop looking at the needle, and just listen. It sounds excellent.

It’s got such an interesting attack-and-release characteristic – both are slow – and if you hit it hard, it just makes things sound creamy. So it sounds great on a bass guitar, and quite often, back in the day, they would have used it on the whole rhythm track. There was a philosophy back then at EMI that you had two basic controls for dynamic control. You had the compressor which was the Altec RS124, or the limiter which was the Fairchild.

It was exciting working with somebody who worked with those pieces of gear and knew them inside out. Just seeing Ken dialling in a sound was amazing.

MT: What was the advice for using the Fairchild?

JB: Just dial it in until it sounds good. His insight was the distortion on the Fairchild was the go-to sound, and he loved it. So, put a vocal through that, and it sounds like a record.

It’s about knowing how to work with analogue gear rather than just thinking about stuff in the box. A point that Ken made was that, even now, there are certain things that you can’t recreate with a plug-in that you can quickly achieve with real hardware.

John: If you were able to record The Beatles in 2019, would you use equipment from their time or all the technology available today to replicate the sound?

JB: That would be dictated entirely by what they wanted to do – and dictated by whoever was producing them. From my point of view, I imagine they would probably feel relatively comfortable working with similar sounds to what they did before because they were good sounds. You’d put a Fairchild on the vocal, have the Altec RS124 on the bass, for example.

The Beatles were pushing boundaries back then, though, so the likelihood is that if you were recording them in a studio now, they’d be trying to push the boundaries even further. I think you’d end up with a hybrid approach. I would be surprised if they weren’t into the idea of recording onto a Pro Tools rig rather than using a tape machine.

Then they would probably try to do all those crazy things that aren’t very easy on a Pro Tools – things that are easier on a tape machine like vari-speed.

You’d probably take a slightly different approach now because their earlier stuff was mixed to four-track so nowadays you’d recording it all separately.

Asa: Is there are specific historical recording session that you would like to have been present for?

JB: I would love to have been there when they were recording Buddy Holly back in the day. That would have been pretty impressive. I’m a total sucker for Curtis Mayfield, The Beatles, The Beach Boys. There are so many! Robert Johnson, The Specials, The Clash. There are loads and loads. Radiohead. They’ve been a massive influence for me.

Curtis Mayfield – you listen to those records, and there’s such an energy. You can hear that everyone is really vibing on it and it would be amazing to have been a part of that. A lot is going on, and it would be pretty hectic, I’m sure, but it sounds like they were having a great time. The other thing is, when you’re working with a great artist, you push the faders up and you look good.

When you’re working with a great artist, you push the faders up and you look good.

I’m pretty confident that if you have John Coltrane and Miles Davis there playing away with their quintet you could put up some mics, push the faders up and put your feet up and say “that sounds incredible”.

If you’ve got a great song, a great artist, great musicians and a great arrangement, then it means that the engineering bit is much easier. Because if all the other parts are sorted, you’ve got a sporting chance of getting something that’s great.

Steph: How strongly does the commercial success of a piece of music depend on the recording engineer (as opposed to the writers and performers?)

You can’t predict commercial success. Sometimes things are commercially successful, and sometimes they aren’t. So, the success of something is probably dictated by whatever the weakest link in the chain is.

Everyone has an important role in that but if the song isn’t very good – even with the best engineer in the world – it’s probably not going to have any commercial success.

But then if you have the best song in the world and it’s poorly engineered, you’re not necessarily going to have a great hit. When it comes to the mix, you can dramatically change the excitement of a track by tweaking things and finding what the most important part of that song is. Is it the hook? Is it the bass line? Is it the guitar? When it comes to the chorus, does it pop enough? Is the vocal sound intimate enough, or is it too far back? Those factors can certainly impact and influence whether something has commercial success.

Also, when you’re engineering something like that, you end up trying to suggest certain things. So you might talk about the arrangement. That’s a mistake that people make quite often. They over-egg an arrangement, so there’s too much stuff going on, and sometimes an experienced engineer can suggest that you don’t need anything more. Maybe, for example, in the verse, it should just be drums and bass, and the acoustic guitar only comes in for the pre-chorus or something like that. That can help change the impact of the song.

A classic mistake that we’ve all also made is saying “let’s double-track the guitar.” You don’t necessarily need to double-track it. Maybe it does sound great double-tracked but try it without a double-track. You could always record the double-track and then mute it later. I think sometimes people get too precious. Just because you have a third keyboard part in there, you don’t necessarily have to use it in the mix. Or maybe it only needs to feature in a short section. The skill of a great mixer is being able to understand what makes that track magical. It might be a sound; it could be a lick. It could even be a gimmicky sound effect. But it’s navigating your way through that.

MT: When you record, do you think about how much freedom you want to give the mix engineer?

JB: I think when I was first engineering, I would say “commit stuff.” There’s something to be said for using all that analogue gear – you can EQ and compress to tape (or Pro Tools) and dial in the sound. But sometimes you can back yourself into a corner, and the other thing is that maybe the decision you made on the tracking day wasn’t necessarily the right one. So there’s a lot to be said for hedging your bets a little bit, without putting off too many decisions until further down the line.

If you’re working with an artist that has a clear vision for what they want to achieve, or you’re there with a producer who knows what they want to make, you can tailor your approach to what they would like.

A classic mistake that we’ve all made is saying “let’s double-track the guitar.”

Some people will say outright “Go ahead, compress the vocal on the way in because I’m only going to do it later.” Then there will be other people who say “No, don’t touch that. We can deal with the compression later with a plug-in so we can tweak it.”

The middle ground is giving a mixer a compressed vocal and an uncompressed vocal, so then they have options. Typically if I were recording a rock ‘n’ roll multitrack, I would see what the producer or mixer wanted. But I think there’s mileage in trying to commit some of it and sculpt sounds. By default, you end up deciding some things because of the microphones you choose. That determines certain things, but even with that in mind, you could put two sets of overhead mics up, so you have the option. Or, on a guitar cab, you might put up a ribbon and a dynamic, or ribbon and a condenser, so you’ve got two different flavours. It’s a project-dependent thing.

I like committing, so I will often compress a few things on the way in, EQ quite a bit on the way in, especially with close-mic’d pop stuff.

You also learn discipline from recording film scores – when you’re recording an orchestra you’re generally trying to keep it clean and flat. It’s all about gain structure and providing all of the options available for later when you, or someone else, comes to mix it. You need to provide lots of different options to people and different perspectives of the sound. Generally, it would be the mid, the close and the far mic. That’s the standard thing nowadays – that you have three layers of perspective.

Read John Barrett’s other insights into vocal mic selection and how to finish a mix, and get an insight into how the Avengers: Endgame soundtrack was recorded.

Read all the instalments of Ask Abbey Road here.